Islamic Calligraphy: Reverential Roots and Decorative Uses

By Isoken Osagie and Content Team •July 2022•6 Minute Read

Pen Box, late 13th–early 14th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain. This intricately designed writing case is covered on the inside and outside with Arabic inscriptions which partly list titles of Mamluk Sultans.

Appreciated worldwide for its refinement and intricacy, Arabic calligraphy has been practiced for centuries. Rooted in Islam, the artform began as a reverential way to further the reach of the Qur’an. Eventually, artists integrated calligraphy into the decoration of secular, everyday stone and ceramic objects.

Arabic calligraphy was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2021. On its website, UNESCO wrote, "The fluidity of Arabic script offers infinite possibilities, even within a single word, as letters can be stretched and transformed in numerous ways to create different motifs."

Abdelmajid Mahboub from the Saudi Heritage Preservation Society, representing one of the sixteen countries that nominated the artform for the honor, emphasized that calligraphy "has always served as a symbol of the Arab-Muslim world."1

But Arabic calligraphy's status as a world treasure also means it needs protection. Today, the conveniences of modern technology challenge the historical art form. As with other written languages, handwritten Arabic is becoming a rarity.

Historical Context

There are six main styles of Arabic or Islamic calligraphy: Kufic, Naskh, Muhaqqaq, Diwani, Thuluth, and Reqa’. The development of Arabic calligraphy goes back to the origin of Arabic script in the 4th century. Arabic belongs to the Semitic family of languages. Known as Arabic abjad, the Arabic writing system is composed of 28 letters, representing consonant phonemes. Vowels are usually inferred by the reader.

Arabic is written and read from right to left. Each letter takes one of four forms depending on its position relative to other letters in a sentence. Characters are joined to one another in a flowing script—which allows calligraphic styles and designs to accommodate a variety of purposes and tastes.

The Illuminated Qur’an

In the Muslim tradition, Allah used the Arabic tongue to reveal the word of Islam to the Prophet Muhammad. Arabic calligraphy was first used to write the Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, and ranks above all other art forms in Islamic art.

Qur’an manuscripts were enhanced using Arabic calligraphy as early as the 7th century CE. Calligraphers and iIlluminators formed the letters using colorful ink and lacy motifs, often set against dynamic patterns.

Surviving Qur’an folios from this early period spotlight the creative ways calligraphers beautified the script, such as exaggerating punctuation marks and accents. Still, such embellishments were made with care to avoid distracting from the holy text. Highlights of distinguished works by Arabic calligraphers can be found in the collection on this site Golden Folio: Gold Leaves from the Tree of Qur’ans.

Calligrapher’s Training and Tools

The art of Arabic calligraphy is primarily passed directly from teacher to student, often within the same family. Historically, calligraphers are educated men from upper-class families, including governors and kings, able to dedicate themselves to the tradition. Students observe their teacher’s models and copy them repeatedly. It takes years of comprehensive, laborious training to obtain a professional calligrapher’s diploma, or Ijazah.2 This certificate is also a student’s final test: the apprentice renders a complex masterpiece, and their teacher signs it.

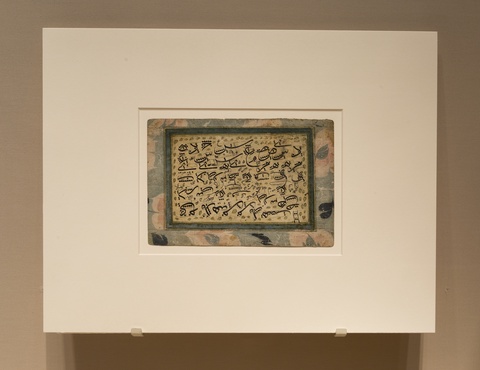

Icazetname of Mir Mustafa Celaleddin, 1853-54 CE. Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum. This icazetname, as the diploma was known in the Ottoman Empire, was awarded to Mir Mustafa Celaleddin upon his completion of training as a calligrapher.

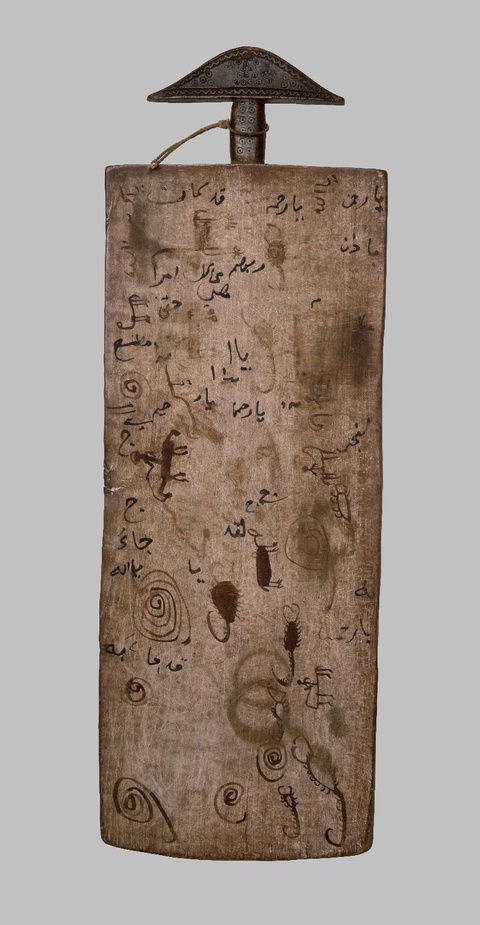

The condition of an artist’s implements affects the quality of their work. As such, calligraphers in training are taught to prioritize care for their materials. The tools required, like reed pens (known as qalam), inks, inkwells, writing boards, shears, knives, pen boxes, and paper, are often themselves showcases of the calligraphic arts. A pen box’s interior would include designated spaces for holding the inkwell and storing pens and penknives, while the whole surface could be intricately adorned with calligraphic flourishes. The beautification of tools alludes to the esteem of Arabic calligraphy in Islamic society. Tools were and continue to be made from exquisite materials such as jade and gold.

A Flowering of Scripts

As Islam’s influence grew, scribes from different cultures made copies of the Qur'an. Calligraphic styles evolved accordingly.

Kufic Script

Named after the Iraqi city of Kufa and derived from the Nabataen alphabet, Kufic was the most popular script during the 8th century. Its popularity in handwriting waned in the 10th century, although it still appears in decoration. The dignified style is characterized by its angular form and horizontality. Several other variations of Kufic emerged over time, including floral, foliated, plaited or interlaced, bordered, and squared styles.

This inkwell found in Iran is an example of what could have been used by a calligrapher around the 11th century. The piece features a floriated Kufic style, ornamenting the boxy Kufic script with curvilinear floral flourishes.

Naskh Script

The origins of Naskh can be traced to Mecca and Medina, two of Islam’s holiest cities. It is compact and rounded, and often used as a cursive script. Naskh dates back to the 10th century, and gained favor due to its legibility. An example of Naskh script can be seen on the inkwell below.

Along with Kufic, Naskh was often used to write the Qur’an. As the centuries progressed, Naskh’s clarity made it the script of choice for the text of official and religious documents, while Kufic provided contrast and decoration.

… And Others

From these beginnings, a plethora of other Arabic scripts evolved to suit different purposes and tastes, often blending or modifying existing varieties. Thuluth is a variation of Kufic that replaced the older style’s somewhat boxy angles with sloped, lithe lines. This is the script commonly seen in mosque decorations from the medieval and Ottoman periods.

Diwani, a relatively new variation, was developed in the Ottoman Empire during the 16th century. It is characterized by dense, interlocking forms bounded by an overall shape, and sometimes constituted the signatures of sultans. Muhaqqaq, in contrast, is stately and upright; its name means “clear.” And Reqa’, an elegant ancient script popular for writing letters, lives on in its simplified modern form, Ruq’ah, still used for signage and correspondence.

Islamic Calligraphy in the Secular World

Given the cultural prohibition against figural representations in Islam, calligraphy blossomed as a creative art form. Quranic verses, beautifully rendered in script, grew to cover everyday items from tableware to jewelry to wall hangings.

Decoration and Innovation

In recent years, contemporary spins on the ancient art form have gained traction. As artists feel unbound by calligraphy’s formal rules, they might also grow distant from its religious origins in the Qur’an. In contemporary decorative contexts, questions around reverence, tradition, and design intertwine.

Despite this, some see modern innovations to Arabic calligraphy as a way forward. Creative changes have contributed to the art form since the beginning. Indeed, Arabic script has come into its own due to its adaptability to a range of formal and historical contexts—from grand mosques to dinner plates, from pen cases to the word of God.

Isoken Osagie is a contributor from the Curationist Content Team. She has worked on various curatorial projects including exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum and Zoma Museum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She is a graduate of The New School in New York City. Her interests include African literature, cultural heritage and the intersections of art and technology.

Citations

“Arabic Calligraphy is Now on UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage List.” The National News, December 14, 2021. https://www.thenationalnews.com/arts-culture/art/2021/12/15/arabic-calligraphy-is-now-on-unescos-intangible-cultural-heritage-list/. Accessed Aug 31, 2022.

“Icazetname of Mir Mustafa Celaleddin.” Sabancı Üniversitesi Sakıp Sabancı Müzesi, Istanbul, Turkey, https://www.sakipsabancimuzesi.org/en/collections-and-research/collections/340/249. Accessed Aug 31, 2022.

Isoken Osagie is a contributor from the Curationist Content Team. She has worked on various curatorial projects including exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum and Zoma Museum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She is a graduate of The New School in New York City. Her interests include African literature, cultural heritage and the intersections of art and technology.