Women Artists, the Enlightenment, and Extraction

By Reina Gattuso•May 2024•19 Minute Read

Rosalba Carriera (Italian, 1675–1757), A Woman Putting Flowers in Her Hair, 1710, Cleveland Museum of Art. CC0.

A small group of women in early modern Europe and North America defied patriarchal restrictions to emerge as well-known artists. Like their male contemporaries, they were part of a global system of inequality established through European colonialism.

From the 16th to the 19th century, European women artists increasingly pushed past male gatekeepers to gain recognition for their work. In doing so, they advanced women’s cultural visibility. Yet these women artists worked within, contributed to, and benefitted from Europe’s growing colonial domination.

This feature will examine the work of several early modern European women painters within this emerging system from the perspectives of the materials they used and the ideologies their work helped to perpetuate.

In the early modern period, scholars in Europe engaged in a broad shift in scientific and philosophical inquiry often referred to as the Enlightenment. This intellectual movement emphasized that the world could be known through secular human reason and empirical study. Enlightenment institutions were economically and culturally embedded in European colonialism. Enlightenment thinkers were, on the whole, part of the project of knitting together the diverse regional and ethnic identities of the European peninsula into the fiction of a distinct and “superior” Western civilization.1 This is part of the invention of the modern system of race.2 Profits and products of slavery funded these inquiries.3

Many of the Europeans who grew wealthy from colonialism purchased art outside traditional systems of church and royal patronage.4 European women artists benefited from these emerging markets, by selling their work and thus gaining economic autonomy and social prestige.

Curationist’s partner institutions, like other encyclopedic museums, are entwined with Enlightenment-era legacies of colonial power and profit.5 They also tend to reflect Euro-American conceptions of the artist as a sole creator. Because of this, a disproportionate number of named women artists in these collections are individual white Europeans and Americans, many from the early modern period.

By studying European and Euro-American women’s works within a global context, we can trace the development of art markets as part of emerging global economic and cultural systems. And we can acknowledge these artists’ under-recognized talent as compared to their male counterparts while critiquing their complicity in colonial structures that harmed people worldwide.

Female Artists and the Early Modern Self: Sofonisba Anguissola and Artemisia Gentileschi

In the late 16th century, several notable women artists broke gender barriers in the wealthy city-states that preceded modern Italy. They included Sofonisba Anguissola and Artemisia Gentileschi.

Women artists were relatively few. Those that did practice were often trained by their fathers. Gentileschi received the majority of her training from her father, artist Orazio Gentileschi. Anguissola, the daughter of minor nobility, received painting training as part of her aristocratic education. She apprenticed with a master painter, which was rare for a woman at the time.6 Artemisia became one of few women painters to be admitted to the Florentine Accademia delle Arti del Disegno.7

Gentileschi’s and Anguissola’s largely male contemporaries saw them as wonders and aberrations, since artistically talented women were considered unusual.8 In their work, both displayed confidence in their talents and unique positions as women artists. Anguissola, for example, was a prolific self-portraitist. Gentileschi depicted herself as the very allegory of painting.

Sofonisba Anguissola, Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola, 1559. Pinocoteca Nazionale, public domain. Anguissola playfully depicted her teacher painting her own portrait – implying in the process that she was the better artist.

The two women’s work often subtly critiqued sexism. Around 1559, for example, Anguissola painted Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola, depicting her teacher Bernardino Campi painting her portrait. Anguissola’s image looms before Campi like an idol, larger and more central than him—suggesting, correctly, that she is whom history will best remember. Anguissola painted her meta-portrait in an imitation of Campi’s style, while she painted Campi in her own style—showing herself the better painter.9

Meanwhile, in a letter to her patron, Gentileschi wrote with braggadocio, “And I will show Your Most Illustrious Lordship what a woman can do.”10

Male instructors were often violent gatekeepers. The artist Agostino Tassi, who some historians believe had been hired by Gentileschi’s father as an additional art instructor, raped Gentileschi in 1611. She was 17. She endured physical torture during the subsequent trial, and was married off in another city.11 Gentileschi’s marriage seemed to afford her the stability to start fresh. She ultimately seems to have parted ways with her husband. She went on to enjoy a life of professional and sexual independence.12

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant, 1615. Pitti Palace, public domain. Artemisia Gentileschi’s rendition of the Biblical story of Judith depicts a more emotionally charged scene than many of her contemporaries.

Many scholars read Gentileschi’s work as informed by her experience of rape, positioning her history paintings especially as taking a stance of feminist resistance. Others argue that this is reductive.13 For example, some scholars interpret her rendition of Susana and the Elders as an expression of anguish from harassment that may have led up to the assault.14 Regardless, the painting is notable in being one of the first European paintings to show that particular biblical story from the victim’s perspective. Surely, 17-year-old Gentileschi, like most teen girls in patriarchal contexts, knew the fear of sexual violence.15 Gentileschi painted multiple depictions of the biblical story of Judith over several years, including Judith Beheading Holofernes and Judith and her Maidservant. The paintings portray Judith and her maidservant as brave women acting in solidarity to defeat an oppressive ruler.

Gentileschi’s work also bears the mark of racist hierarchies borne of European empire and transatlantic slavery. In her rendering of another biblical heroine, Esther Before Ahasuerus, for example, Gentileschi added, then painted out, an image of an African person serving the other characters, who are depicted as European. The figure is still partially visible under the painted marble floor.16

Some scholars argue that, in the late 15th century, Italian painters began including more depictions of African people in portraits of European nobility to signal European imperial power.17 We can read the erased presence of an African person in Gentileschi’s work as a metaphor for the ways mainstream histories often erase underlying colonial violence from narratives of European women’s progress.

Representing the Natural World: Botanical Illustration, Animaliéres, and Ivory

Europeans brought animals, plants, and pathogens to the places they colonized, and extracted the same. Women took part in this process as botanical collectors (in both the colonies and Europe), documentarians, and artists.18 European women artists incorporated animals and plants into their work, either portraying them or using them as materials. Botanical illustration, animal paintings, and painting on ivory reveal how colonial encounters shaped European understandings of the natural world as subject and material.

Botanical Illustrators: Clara Peeters, Maria Sibylla Merian, and Anna Atkins

European still life painters often portrayed flowers as allegories for virtues — lilies, for example, typically symbolize purity in association with the Virgin Mary.19 Yet these paintings also reveal the global circulation of plants and botanical knowledge between European imperial centers and colonies. This traffic in plants was part of the formation of the plantation system and the dawn of modern finance capital. For example, the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1600s was the first known capitalist bubble.20

Europeans didn’t divide art and science into two separate spheres of knowledge until the 19th century.21 Studying early modern still lives and botanical illustrations together can help modern audiences understand how visual observation informed the development of both disciplines.

Flemish still life painter Clara Peeters was one of the only well-known women artists in Northern Europe in the early 1600s.22 Her paintings of cheeses, meats, and fruits in ornate metal platters depicted the luxuries elites could access.23 Her floral paintings, such as her 1612 A Bouquet of Flowers, demonstrate extraordinary detail—insect bites, dewdrops, shadows, and wilting. A yellow and red-striped tulip shoots out from the upper right hand side of the bouquet—reflecting the emerging Dutch market in tulips, imported as a prized and “exotic” rarity from the Ottoman Empire.24

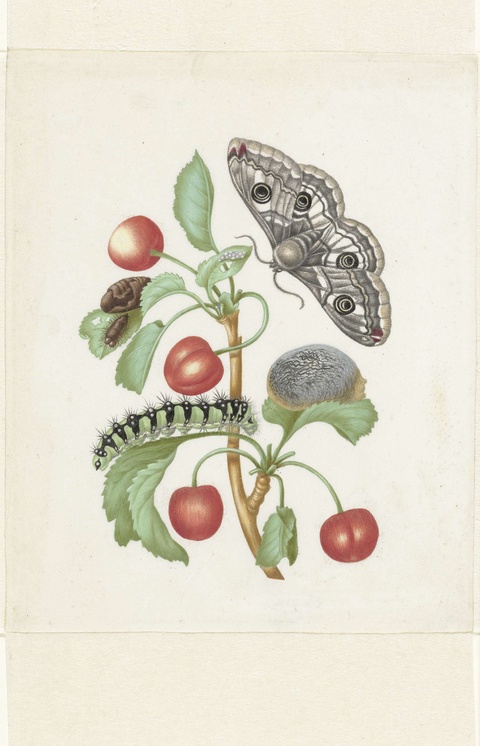

German naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian trained in painting still lifes and botanical illustrations in Europe, then traveled to the Dutch colony of Guiana in 1699 to document the region’s insects.25 Merian was one of several European women who went to the Americas and other places colonized by European powers to document plants and animals. She was one of the first scientists to document butterflies’ process of metamorphosis.26

Like other European naturalists of the time, Merian drew on the deep knowledge of local Indigenous and Black people in Guiana. While Merian mentioned these interactions in her work, scholar Tomomi Kinukawa argues that she neglected to question the broader colonial system that made these relationships deeply unequal.27

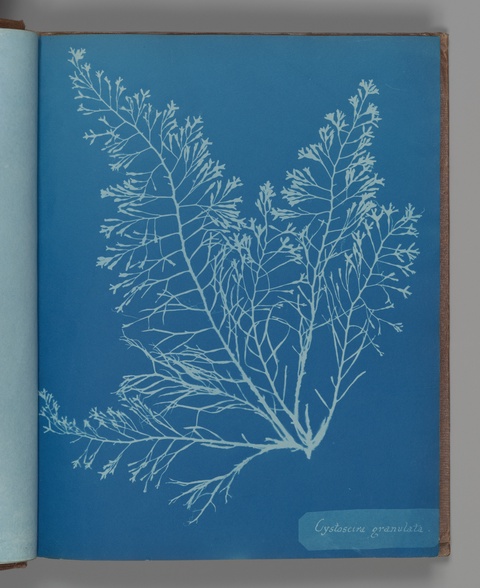

Over 100 years later, British naturalist, botanical illustrator and photographer Anna Atkins created the world’s first known photography book, a cyanotype collection of British algae. In the cyanotype process, objects placed on photosensitive paper leave ghostly white negatives on a sea of blue. Atkins’ father worked at the British Museum, exposing her to a wide range of art and botanical specimens, including from places the British colonized.28

Scholar Sophia Franchi argues that we can recast Atkins’s work, and thus both botany and photography, within a history of women’s handicrafts.29 By considering the labor and craft of botanical collection and illustration, we can challenge the historical understanding of science as exclusively belonging to the male elite.

Animalière: Rosa Bonheur

French artist Rosa Bonheur, active in the mid- to late-19th century, became famous as an animaliére, or animal portraitist. Bonheur defied gendered expectations by presenting as masculine, partnering intimately with women, and controlling her economic destiny. She painted domesticated animals including dogs and, especially, cattle.30

Bonheur’s fascination with cattle mirrors the broader interest in animal breeding in Europe at the time. Farmers wanted to maximize the meat, milk, and strength of these animals. Artists and natural historians, including Bonheur, produced texts cataloging different animal breeds. Agriculturalists were interested in animals imported from beyond Europe, such as the Tibetan yak.31

Bonheur’s images ennoble these efforts. We can observe a sense of heroic physical mastery in the low angle from which Bonheur paints muscular oxen as they strain to pull a plough through the idyllic French countryside.

Scholar Stephanie Triblett argues that Bonheur’s paintings convey respect for the cattle. Yet Triblett also urges us to understand Bonheur’s interest in breeding cattle for physical “perfection” as part of an exploitative capitalist and colonial economic network that sought to maximize productivity.32

Ivory Miniaturists: Rosalba Carriera and Sarah Goodridge

Women artists’ paintings on ivory reveal both colonial networks of resource extraction, and imagery that helped define modern notions of race. Here, we’ll focus on 18th-century Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera and 19th-century Euro-American painter Sarah Goodridge.33

People in what we now call Africa, especially the Kongo region, have long used ivory to create powerful objects for elite use.34 Similarly, people in what we now call Europe have used ivory (first sourced in Europe, then Africa) as a medium since prehistoric times.35 In the 17th century, Portuguese merchants, and soon other Europeans, dramatically increased ivory trade with West-Central Africans. This shifted Kongolese cultural production.36

As scholar Inji Kim explains, Europeans and Euro-American artists prized ivory as a medium with which to depict pale skin. 18th- and 19th-century elites considered ivory miniature painting a suitably refined activity for women artists, who were assumed to be hobbyists.

Rosalba Carriera was one of the few early modern women inducted into the Paris Academy. She pioneered a technique for painting in gouache on ivory. She decorated many ivory snuff boxes, such as the one pictured here. Her miniatures typically featured European women in alluring poses, showcasing the white luster of the ivory as a means to depict their pale complexions—thus reinforcing the emerging tie between racial hierarchy and skin color.

These visual depictions were part of the emerging construction of race.37 Artists at the time often created allegorical depictions of the “Four Continents”—Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas—as women bearing riches. These stereotypical renderings depicted non-European peoples as freely offering their resources for European imperial trade and consumption.38 Carriera made a series of such allegories, reflecting the increasing importance of visual markers of racial difference.39

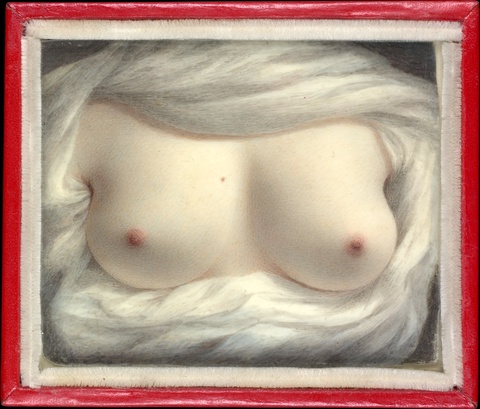

White American artist Sarah Goodridge also specialized in miniature portraits. She originally created her most famous work, Beauty Revealed, as an intimate gift for U.S. statesman Daniel Webster, her possible lover. The painting challenges gendered social strictures. “Goodridge daringly reveals her bare breasts, defying long-standing conventions of modesty and redefining the boundaries of artistic representation,” argues Kim.40

The portrait’s delicacy belies the brutality of both material and recipient. Americans acquired ivory from Africa through a colonial system. Webster, Goodridge’s patron, was a congressman who supported slavery.41 The very grounds for Goodridge’s intimate self-expression is a material extracted through a global system of colonial violence, meant as a token for a powerful and racist white man.

Conclusion

In the early modern period, European and Euro-American women’s emerging self-expression occurred within material systems that exploited Black, Indigenous, and other people in what is now the Global South. This tension haunts feminist movements to this day. It invites us to seek out, and create, feminisms that challenge racist and capitalist violence.

This feature is part five in Curationist’s seven-part series on women artists in our partner archives. For a guide to the series, see the Introduction, “Women Artists and the Museum ."

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

For the relationship between Enlightenment thought and justifications and critiques of colonialism, see: “Enlightenment Thought.” Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/enlightenment-thought. Accessed 1 May 2024. For the history of Europe as a concept, and its ties to race, see: Otele, Olivette. African Europeans. Hurst Publishers, 2020. Black feminist physicist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein has a useful way of reframing European exceptionalism by challenging the construction of Europe as geographically distinct from Asia. She refers to it as “the European peninsula of Asia” in her book, The Disordered Cosmos (McKittrick, Katherine. “Public Thinker: Chanda Prescod-Weinstein Looks to the Night Sky.” Public Books, 3 September 2019. https://www.publicbooks.org/public-thinker-chanda-prescod-weinstein-looks-to-the-night-sky/. Accessed 5 June 2023.).

Bouie, Jamelle. “The Enlightenment’s Dark Side.” Slate, 5 June 2018. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/06/taking-the-enlightenment-seriously-requires-talking-about-race.html. Accessed 31 May 2023. See also: Alpert, Avram. “Philosophy’s Systemic Racism.” Aeon, 24 September 2020. https://aeon.co/essays/racism-is-baked-into-the-structure-of-dialectical-philosophy. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Universities on both sides of the Atlantic — including Cambridge and Harvard — profited immensely from the trade in enslaved African people. Adams, Richard. “Cambridge University Finds it Gained ‘Significant Benefits’ from Slave Trade.” The Guardian, 22 September 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/sep/22/cambridge-university-finds-it-gained-significant-benefits-from-slave-trade. Accessed 31 May 2023. See also: The Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery. “Financial Ties: Harvard and the Slavery Economy.” Harvard & The Legacy of Slavery. https://legacyofslavery.harvard.edu/report/financial-ties-harvard-and-the-slavery-economy. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Wollerstorff, Nicholas. “The Early Modern Revolution in the Arts” in Art Rethought: The Social Practices of Art. Oxford University Press, September 2015. https://academic.oup.com/book/9794.

As of early 2024, all of Curationist’s partner institutions are in the Global North. There has been a huge amount of writing, protest, artwork, and other forms of engagement with the legacies of Curationist’s partner institutions located in imperial centers. A few examples include: an analysis of the Art Institute of Chicago as a white institutional space (Silvia Domínguez, Simón E. Weffer, and David G. Embrick. “White Sanctuaries: White Supremacy, Racism, Space, and Fine Arts in Two Metropolitan Museums.” American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 64, no. 14, 2020. SAGE. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Silvia-Dominguez-3/publication/335802048_White_sanctuaries_race_and_place_in_art_museums/links/626bf99cd49fe200e1c5fe71/White-sanctuaries-race-and-place-in-art-museums.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2023.); protests against the Brooklyn Museum (“Decolonize This Museum.” Decolonize This Place, https://decolonizethisplace.org/bk-musuem. Accessed 1 June 2023.); a performance within the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Nikhil Chopra Sleeps at the Met and Uncovers its Colonial Past.” Frieze, 1 October 2019. https://www.frieze.com/article/nikhil-chopra-sleeps-met-and-uncovers-its-colonial-past. Accessed 1 June 2023.); histories of the Smithsonian Institute as a product and driver of U.S. imperialism (Wintle, Claire. “Decolonizing the Smithsonian: Museums as Microcosms of Political Encounter.” The American Historical Review, vol. 21, no. 5, December 2016. Oxford Academic, https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/121/5/1492/2750774. Accessed 1 June 2023.); and an installation in the Rijksmuseum (McGivern, Hannah. “Revolutionary Rijksmuseum exhibition reckons with Dutch colonial conflict in Indonesia.” The Art Newspaper, 2 March 2022, www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/02/revolutionary-rijksmuseum-exhibition-reckons-with-dutch-colonial-conflict-in-indonesia. Accessed 21 March 2022.).

“Sofonisba Anguissola.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sofonisba_Anguissola. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Cohen, Elizabeth S. “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History.” The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, spring 2000. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2671289. Accessed 31 July, 2023.

Loh, Maria H. “In the Sixteenth Century, Two Women Painters Challenged Gender Roles.” Art in America, 25 February 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/sofonisba-anguissola-lavinia-fontana-italian-renaissance-women-painters-1202678831/. Accessed 2 April 2024.

“In the Sixteenth Century, Two Women Painters Challenged Gender Roles.”

York, Laura. “The ‘Spirit of Caesar’ and His Majesty’s Servant: The Self-Fashioning of Women Artists in Early Modern Europe.” Women’s Studies, vol. 30, no. 4, 2001. Taylor and Francis, https://doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2001.9979392. Accessed 31 July 2023.

Ray, Grace T. O. “The ‘Trans-Historical Community of Women’ and the Paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi.” The Confluence, vol. 2, no. 2, May 2023. Digital Commons at Lindenwood University, https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/theconfluence/vol2/iss2/5. Accessed 31 July 2023.

Mead, Rebecca. “A Fuller Picture of Artemisia Gentileschi.” The New Yorker, 28 September 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/10/05/a-fuller-picture-of-artemisia-gentileschi. Accessed 31 July 2023.

“A Fuller Picture of Artemisia Gentileschi.”

“Susanna and the Elders.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susanna_and_the_Elders_(Artemisia_Gentileschi,_Pommersfelden). Accessed 30 April 2024.

In “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History,” scholar Elizabeth S. Cohen argues that because 17th century Romans held a different understanding of the body, gender, and the social role of sexual violence than many contemporary people, it is anachronistic to assume Gentileschi experienced rape primarily as a traumatic personal violation. “Artemisia spoke of her body during the trial, but as the material upon which a socially significant offense had been committed. More than the internal, private meanings, the external ones troubled her,” she writes.

Cohen’s point that contemporary feminists cannot assume a universal and singular experience of rape, and should not assume that Gentileschi’s experience of sexual violence determined her career, is well taken. However, to say that social, cultural, and legal framings of rape as primarily a crime against a woman’s community would necessarily make the experience of rape less distressing seems suspect. Women’s movements around the world, in many social contexts and eras, have protested sexual violence.

“Esther Before Ahasuerus.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436453. Accessed 31 July 2023.

Bethencourt, Francisco. “Review: Black Africans in Renaissance Europe.” https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/619. Accessed 31 July 2023. For an overview of changing historical depictions and understandings of African people in what is now Europe, see Otele.

Hong, Jiang. “Angel in the House, Angel in the Scientific Empire: Women and Colonial Botany During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Notes and Records no. 75, 2021. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsnr.2020.0046. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Liedtke, Walter. “Still Life Painting in Northern Europe, 1600-1800.” The Met, October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nstl/hd_nstl.htm. Accessed 30 April 2024.

“Dutch Still Lifes and Landscapes of the 1600s.”

Zhu, Lian and Yogesh Goya. “Art and Science.” EMBO Reports vol. 20, no. 2, December 2018. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6362349/. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“The Art of Clara Peeters.” Museo Del Prado, https://www.museodelprado.es/en/whats-on/exhibition/the-art-of-clara-peeters/e4628dea-9ffd-4632-85c9-449367e86959. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Winograd, Abigail. “Setting ‘A Global Table’: Seventeenth-Century Still Life, Colonial History, and Contemporary Art.” In The Transhistorical Museum: Mapping the Field. Eva Wittocx, Ann Demeester, and Melanie Bühler, eds. Valiz/vis-à-vis, 2018. Academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/50323795/Setting_A_Global_Table_Seventeenth_Century_Still_Life_Colonial_History_and_Contemporary_Art. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Goldgar, Anna. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. University of Chicago Press, 2007. Excerpt from Introduction at https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/301259.html. Accessed 29 March 2024.

“Maria Sibylla Merian.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Sibylla_Merian. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Lotzof, Kerry. “Maria Sibylla Merian: Metamorphosis Unmasked by Art and Science.” Natural History Museum, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/maria-sibylla-merian-metamorphosis-art-and-science.html. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Kinukawa, Tomomi. “Science and Whiteness as Property in the Dutch Atlantic World: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium.” Journal of Women’s History vol. 24, no. 3, fall 2012. Project Muse, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/485079. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Lotzof, Kerry. “Anna Atkins’s Cyanotypes: The First Book of Photographs.” Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/anna-atkins-cyanotypes-the-first-book-of-photographs.html. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Franchi, Sophia. “Crafting and Collecting Cyanotypes: Anna Atkin’s Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions.” Literature Compass, 27 May 2023. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12708. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Rosa Bonheur.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Bonheur. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Triplett, Stephanie. “Bovine Reproductions: Animal Husbandry and Acclimatization in the Cattle Paintings and Prints of Rosa Bonheur.” Art History, 8 March 2023. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12707. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Bovine Reproductions: Animal Husbandry and Acclimatization in the Cattle Paintings and Prints of Rosa Bonheur.”

Kim, Inji. “Miniature Portraits Unveiled: Ivory’s Legacy and Artistic Agency.” Curationist, August 2023. https://www.curationist.org/editorial-features/article/miniature-portraits-unveiled:-ivory's-legacy-and-artistic-agency. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Bridges, Nichole N. “Kongo Ivories.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kong/hd_kong.htm. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Venus of Hohle Fels.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_of_Hohle_Fels. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Kongo Ivories.” See also: “Ivory: Significance and Protection.” National Museum of African Art, 2019. https://africa.si.edu/research/conservation/protect-ivory/. Accessed 2 April 2024.

Roediger, David R. “Historical Foundations of Race.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race. Accessed 2 April 2024.

Material culture and written histories tell us that historical peoples in what is now called Europe and Africa identified cultural and physical differences among groups of people. For example, elites from the Greek and Roman mainlands felt themselves different in some ways from those we’d now call Black African people. Yet, as scholar Olivette Otele argues, this difference was constructed more around the notion of the imperial center and periphery. It was not the same as the modern conception of race, which emerged in the 17th century. (Otele, Olivette. African Europeans. Hurst, 2020.)

Gattuso, Reina. “Colonial Allegories of the Dutch East India Company.” Curationist, https://www.curationist.org/curated-collections/bd008a92-698a-4679-9c94-65e9166fd538. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Wunsch, Oliver. “Rosalba Carriera’s Four Continents and The Commerce of Skin.” Journal 18, https://www.journal18.org/issue10/rosalba-carrieras-four-continents-and-the-commerce-of-skin/. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Miniature Portraits Unveiled: Ivory’s Legacy and Artistic Agency.”

“Daniel Webster.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/daniel-webster.htm. Accessed 2 April 2024.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.