How Chocolate Reached the Eastern Hemisphere

By Reina Gattuso•June 2022•12 Minute Read

Unknown, Turkey Vessel, 7th–10th century, Veracruz. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Most likely given as a funerary gift, this turkey vessel signified power and also conveyed hopes for successful growing seasons in the future.

In the past 500 years, chocolate has gone from a spiritually significant Central American beverage to a global culinary commodity. It inspired reverence and debate, while the European appetite for chocolate fueled colonial exploitation. Ceremonial cacao cups and delicate porcelain vessels chart the evolution of this “food of the gods.”

Introduction

Chocolate has played an important role in the culinary and spiritual life of Central and South Americans for thousands of years. Made from the seeds of the cacao tree, chocolate is native to the Amazon.1 Archaeological evidence shows Indigenous Americans used cacao as early as 5,300 years ago.2

Indigenous South and Central American groups primarily consumed cacao as a drink. The Maya and Aztec flavored fermented, ground cacao beans with honey, chili, and annatto (achiote seed), which colored the chocolate red. They added water and beat the beverage until foamy. The Maya and Aztec used cacao as part of rituals of birth, death, marriage, and kingship.3 4

European colonizers came to the Americas searching for a sea route to Asia in order to more easily access the lucrative Southeast Asian spice trade. They wanted nutmeg, but they found cacao. Cacao played a role in early contact between European colonizers and Indigenous Americans. In a 1519 visit to the Aztec court, Spanish colonizer Hernán Cortés and his retinue observed Emperor Moctezuma consume a lavish meal with goblets of cacao.5

At first, Europeans expressed disgust for the bitter drink, calling it “fit for pigs.”6 But Europeans soon developed a taste for cacao. In 1521, the Spanish defeated the Aztec.7 The Spanish were largely outnumbered by the Indigenous people they ruled, and absorbed many local habits such as chocolate-drinking.8 Europeans primarily consumed chocolate as a drink until the 1800s.9

A craze for chocolate transformed the economy, gastronomy, and social customs of Europe and the world. European plantation owners forced enslaved people to grow cacao, and elites drank it. European scientists gave the cacao plant the scientific genus Theobroma, meaning “food of the gods.”10 It caused moral panics, and continues to be marketed as a tempting aphrodisiac.

We can study cacao vessels and depictions of chocolate to learn how cacao went from being a ceremonial Central and South American beverage to a global economic and cultural force.

American Origins

Cacao originated in the Amazon region. Traders disseminated cacao as far north as Chaco Canyon in what is now the southwestern United States.11

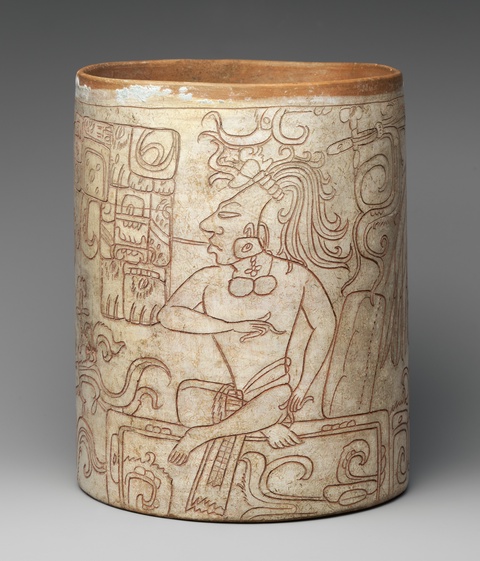

Mayans likely used the pot below to offer a cacao drink to guests at banquets. For this purpose Mayan craftspeople decorated earthenware pots, like this one dated from the 3rd to 6th century CE, with cacao beans and trees.

The incised design on the vessel depicts Hun Hunahpu, the Mayan maize god.12 Here, Hun Hunapu is shown in his avatar as the god of cacao.

Archaeologists theorize that Kaan Took, whose name is inscribed on this vessel, was a Mayan noble from what is now the Tabasco region of Mexico.13 Drawings on the vessel depict the Mayan maize god, demonstrating his association with cacao. A cook, usually a woman, would have poured a prepared chocolate drink into the pot from high above in order to create the drink’s signature froth.14

Similarly, a user of this turkey-shaped vessel from what is now Veracruz, Mexico may have blown into the spout in the back to froth a cacao drink.15 The turkey was important to pre-Columbian North American people as a food source and ritual animal.

European Colonization

When chocolate first reached Europe in the 1500s, it caused a moral panic. Chocolate was the first source of caffeine many Europeans tasted. It was rumored to be an aphrodisiac. Catholic officials debated chocolate’s safety and whether it could be consumed during fasting periods.16

Chocolate won the debate. By the 1700s, chocolate houses became popular meeting places for posh Europeans.17 Europeans added sugar to the drink, and flavored chocolate with cinnamon and other spices from European colonies in Asia.18 Spanish, French, British, and Dutch elites forced enslaved African and Indigenous people to grow cacao and sugarcane at plantations in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.19

Chocolate Sweeps Europe

The colonial plantation system, built on the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people, brought astronomical wealth to Europe. Elite Europeans commissioned precious vessels to serve equally costly cacao.

This luxurious gold, glass, and porcelain hot chocolate set is from the late 1730s in Vienna. The elaborate gold fittings demonstrate the opulence and prestige of chocolate drinking.

This porcelain sculpture, also from late 1730s Vienna, shows an aristocratic lady taking her morning chocolate and biscuits. A Black domestic laborer serves her. Africans experienced appalling racism in 18th century Vienna.20 The server’s presence evokes the broader European colonial trade in plantation commodities and enslaved human beings.21

Colonial Americas

Cacao continued to be popular in the Americas during the colonial period. Non-Indigenous communities in Spanish colonies adapted chocolate drinking, thanks partly to the influence of Indigenous women domestic and healing workers.22

This 18th-century Puebla majolica jar is an example of talavera poblana. Originally inspired by Spanish dishware imported into what is now Mexico, talavera poblana designs reflected the Arab, Italian, French, and Chinese influences in Spain. This piece, painted with a long-tailed bird framed by scrolls, may have been inspired by Chinese export Swatow or Zhangzhou ware.23 The iron lock at the top of the pot shows that it likely held precious ingredients, including cacao.

Chocolate was a rare, costly commodity in colonial North America and the early United States. Chinese artists made jugs like this for export in the early 19th century. The powerful New York Wyckoff family owned the jug. This kind of jug would normally have been used in the United States for cider. The Wyckoffs used it for chocolate, demonstrating their wealth.24

Exporting the Plantation System

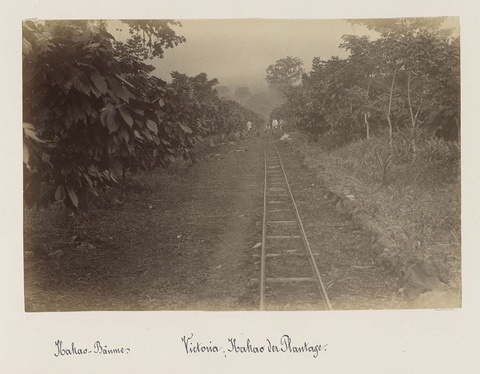

By the early 1800s, many American colonies had rebelled against their European colonizers. Enslaved people fought for their liberation. In response, European producers moved many cacao plantations to West Africa.25 For most of a century, 90% of the African continent was under brutal European colonial control.26

This 1899 photograph depicts a cacao plantation in German-controlled Cameroon. The violent plantation system increased the supply of cacao in Europe and the U.S., making chocolate more affordable.

In this 1897 advertisement for a chocolate company, a young woman pours hot chocolate for a well-dressed Dutch lady. The young woman wears traditional dress, indicating Dutch pride for their chocolate production.

Many European powers became famous for chocolate confections, yet this ignores the brutality at the heart of their production system. Belgian chocolate remains an important part of its economy even today.31 32 The celebration of chocolate confectionery overlooks the horrific atrocities Belgian colonizers committed against Congolese people in order to extract materials like cacao. Belgium’s colonial system killed up to 10 million Congolese people between 1885 and 1908, through murder, disease, famine, and mass displacement.33

Twentieth-century artists in West Africa included cacao in their iconography, for example in a wood stool depicting a person harvesting ripe cacao from a tree.34

Chocolate in Modern life

As of 2020, the global chocolate industry was valued at US$138.5 billion.35 The chocolate industry is largely controlled by several global-North multinational corporations, who mostly buy from plantations in West Africa.36 Some chocolate producers have attempted to create supply chains with better environmental and labor practices.37 But this is arguably a Band-Aid on a vastly exploitative system with deep colonial roots.

Chocolate advertisements in the English-speaking world continue to reflect the initial Christian ambivalence toward chocolate.38 Advertisers commonly depict chocolate as “sinful,” or associate it with the sexualization of young women.39

Contemporary art institutions have attempted to address the colonial origins of cocoa. For example, the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC), founded by white Dutch artist Renzo Martens, supports cacao plantation worker-artists in showing and selling their art abroad. Critics have labeled Martin’s effort a form of neocolonialism, though many local artists say they’ve benefitted from the project.40 41

Both the global chocolate industry and the art market offer luxury products with roots in colonialism. Many global art institutions are funded by capitalists who extracted their wealth from the plantation system.42 Groups like CATPC attempt to use art to return this plantation wealth back to the workers from whom it was originally exploited. True reparations for the racist brutality of the plantation system, however, would require a vast global redistribution of power and resources.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Suggested Readings

Doyle, James. “The Drinking Cup of a Classic Maya Noble.” The Met, 25 September 2014, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2014/maya-drinking-cup.

Earls, Averill. “Hot for Chocolate: Aphrodisiacs, Imperialism, and Cacao in the Early Modern Atlantic.” Dig, 5 July 2020, https://digpodcast.org/2020/07/05/hot-for-chocolate-aphrodisiacs-imperialism-and-cacao-in-the-early-modern-atlantic/.

Carr, Teresa. “The Bitter Side of Cocoa Production.” Sapiens, 13 February 2020, https://www.sapiens.org/culture/cocoa-production/.

Samudzi, Zoé. “The Sculptural Politics of Cacao.” Art in America, 15 September 2020, www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/congolese-plantation-workers-art-league-cacao-sculptures-1234570834/.

Eisenstadt, Abigail. “What Chocolate-Drinking Jars Tell Indigenous Potters Now.” Smithsonian, 7July 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2020/07/07/what-chocolate-drinking-jars-tell-indigenous-potters-now/.

Citations

“Chocolate.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chocolate. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Chocolate.”

McNeil, Cameron L., ed. “Summary.” Online summary for Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao. University Press of Florida, 2009. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/book/17463. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury.” The Field Museum, 2007, archive.fieldmuseum.org/chocolate/history_mesoamerican5.html. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Zolov, Eric, ed. “Chocolate.” In Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo, 2015, ABC-CLIO, pp. 165. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Iconic_Mexico_An_Encyclopedia_from_Acapu/yvtPCgAAQBAJ. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Gershon, Livia. “How Chocolate Came to Europe.” JSTOR Daily, 30 January. 2019, daily.jstor.org/how-chocolate-came-to-europe/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Hudson, Miles. “Battle of Tenochtitlan.” Britannica, www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Tenochtitlan. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Norton, Marcy. “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internationalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics.” The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 3, June 2006, pp. 660-691. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ahr.111.3.660. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Chavers, Penny. “Chocolate - Food of the gods.” History Daily, historydaily.org/chocolate-food-of-the-gods. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Fiegl, Amanda. “A Brief History of Chocolate.” Smithsonian Magazine, 1 March 2008, www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/a-brief-history-of-chocolate-21860917/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Eisenstadt, Abigail. “What Chocolate-Drinking Jars Tell Indigenous Potters Now.” Smithsonian, 7 July 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2020/07/07/what-chocolate-drinking-jars-tell-indigenous-potters-now/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“The Maya Maize God.” The British Museum, www.teachinghistory100.org/objects/abouttheobject/maize_god. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Vessel with Seated Lord.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/316711. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Doyle, James. “The Drinking Cup of a Classic Maya Noble.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25 September 2014, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2014/maya-drinking-cup. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Turkey Vessel.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/317619. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Miller, James C. “Cacao Cravings: Europe’s Assimilation and Europeanization of Chocolate Drinking from Mesoamerica, 1492-1700 C.E.” Inquiries Journal, vol. 9, no. 10, 2017, pp. 2-21, www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1669/2/cacao-cravings-europes-assimilation-and-europeanization-of-chocolate-drinking-from-mesoamerica-1492-1700-ce. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“The Importance of English Chocolate Houses.” Chocolate Class, 20 February 2014, chocolateclass.wordpress.com/2014/02/20/the-importance-of-english-chocolate-houses/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Klein, Christopher. “Chocolate’s Sweet History: From Elite Treat to Food for the Masses.” History, 2 January 2021, www.history.com/news/the-sweet-history-of-chocolate. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Pinero, Eugenio. “The Cacao Economy of the Eighteenth-Century Province of Caracas and the Spanish Cacao Market.” The Hispanic American Historic Review, vol. 68, no. 1, February 1988, pp. 75-100. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2516221. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Wigger, Iris and Spencer Hadley. “Angelo Soliman: Desecrated bodies and the spectre of Enlightenment racism.” Race and Class, vol. 62, no. 2, 3 August 2022, pp. 80-107. SAGE Journals, journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306396820942470. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Cacao’s Migration to Africa.” Chocolate Class, 25 March 2020, chocolateclass.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/cacaos-migration-to-africa. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internationalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics.”

“Chocolate Jar with Iron-Locked Lid.” The Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artworks/10703/chocolate-jar-with-iron-locked-lid. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Jug.” Brooklyn Museum, www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/660. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Cacao’s Migration to Africa.”

“Scramble for Africa.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ScrambleforAfrica. Accessed 2 April 2022.

“A Brief History of Chocolate.”

Birch, Kate. “Top 10 Largest Chocolate Companies.” Food, 7 July 2021, fooddigital.com/food/top-10-largest-chocolate-companies. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“A History of Goodness.” Hershey, www.thehersheycompany.com/en_us/home/about-us/the-company/history.html. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“The Nestlé Company History.” Nestlé, www.nestle.com/aboutus/history/nestle-company-history. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Belgian Chocolate.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgian_chocolate. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“The Belgian market potential for cocoa.” CBI Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 14 January 2020, www.cbi.eu/market-information/cocoa-cocoa-products/belgium/market-potential. Accessed 2 April 2022.

“Atrocities in the Congo Free State.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atrocities_in_the_Congo_Free_State. Accessed 10 May 2022.

“Stool with Cocoa-Pod Harvester.” Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artworks/213619/stool-with-cocoa-pod-harvester. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Fior Markets, “Global Chocolate Market is Expected to Reach USD 200.4 billion by 2028.” GlobalNewswire, 25 May 2021, https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2021/05/25/2235030/0/en/Global-Chocolate-Market-Is-Expected-to-Reach-USD-200-4-billion-by-2028-Fior-Markets.html. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Baron Cadloff, Emily. Modern Farmer, 25 October 2021, https://modernfarmer.com/2021/10/bean-to-bar-ethical-chocolate/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Carr, Teresa. “The Bitter Side of Cocoa Production.” Sapiens, 13 February 2020, https://www.sapiens.org/culture/cocoa-production/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Earls, Averill. “Hot for Chocolate: Aphrodisiacs, Imperialism, and Cacao in the Early Modern Atlantic.” Dig, 5 July 2020, https://digpodcast.org/2020/07/05/hot-for-chocolate-aphrodisiacs-imperialism-and-cacao-in-the-early-modern-atlantic/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“Cocoa As Corruption: The False Association Between Chocolate and Unholy Indulgence.” Chocolate Class, 24 March 2020, https://chocolateclass.wordpress.com/2020/03/24/cocoa-as-corruption-the-false- association-between-chocolate-and-unholy-indulgence/. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Fox, Dan. “Renzo Martens.” Frieze, 1 April 2009, https://www.frieze.com/article/renzo-martens. Accessed 22 March 2022.

“The Sculptural Politics of Cacao.”

Siegal, Nina. “With a New Museum, African Workers Take Control of Their Destiny.” The New York Times, 13 April 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/13/arts/design/white-cube-renzo-martens.html. Accessed 22 March 2022.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.