Women Artists and Powerful Patrons

By Reina Gattuso•March 2024•15 Minute Read

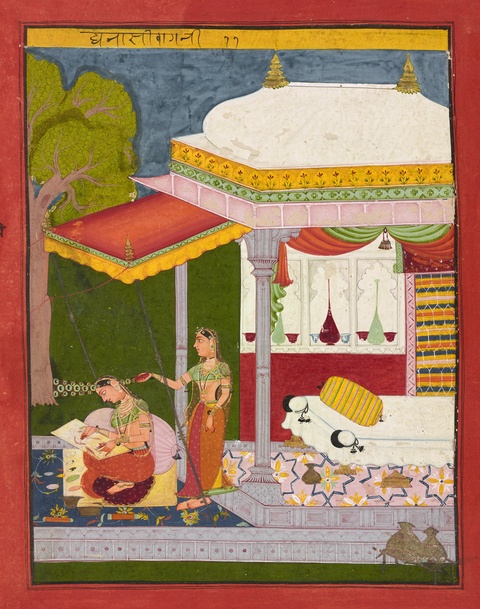

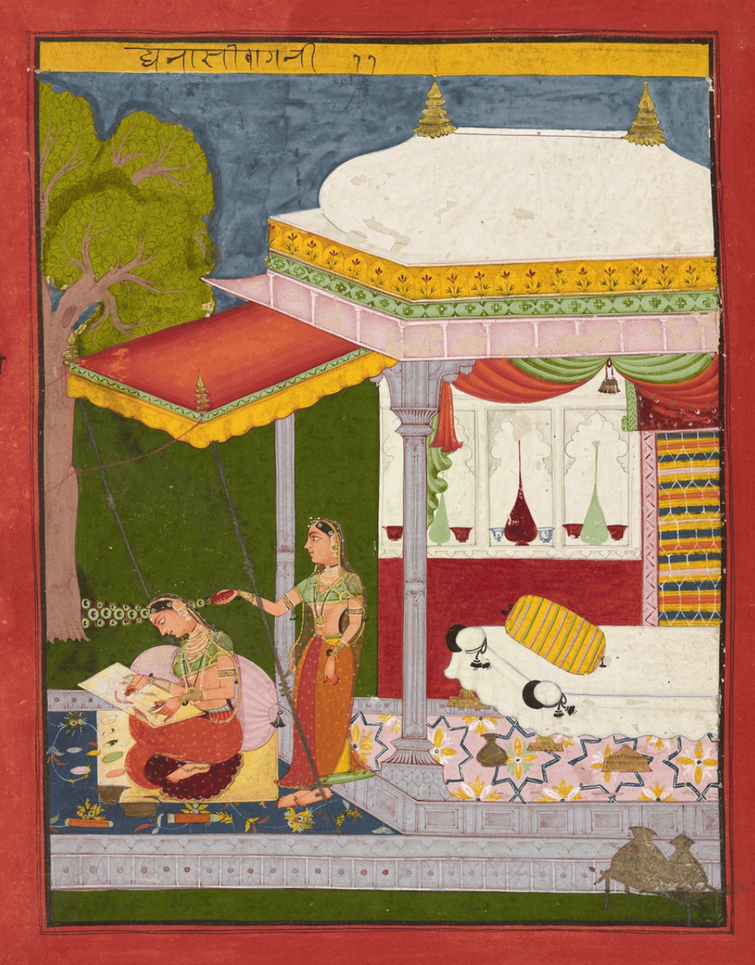

Dhanasri Ragini, 1680s, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, CC0.

Across time and place, political rulers have patronized the arts as a means of glorifying divinities and themselves. Women artists have often worked in these systems. In some contexts, they occupied marginal roles, earning renown despite gender restrictions. In others, women were at the heart of imperial creative production.

Through the millennia of human civilization, rulers have frequently supported artmaking. Royalty might patronize workshops of artists based in their courts. These court artists produced works for the state treasury, diplomacy, religious functions, or the personal enjoyment of rulers. This feature will examine works created by women laboring in state-sponsored workshops or royal courts.

Frequently, royal workshops included artists who specialized in different skills, with various apprentices and workers laboring under them. Royalty might also patronize family-run workshops, in which male heads employed their daughters and sisters to do more menial tasks.1 Because of this collective authorship, we often don’t have records of individual creators’ names. The head of a workshop might sign their own name to their apprentices’ and assistants’ work, which could obscure traces of women’s contributions.2

State-sponsored production systems created a visual language that reinforced the ideology of the ruling dispensation. Sometimes, however, artists slyly critiqued their patrons, and women artists sometimes challenged male gatekeepers. For example, in early modern Europe, women court painters engaged in the practice of paragone alongside their male peers and teachers, riffing on rival male artists’ works as a form of braggadocio.3

In keeping with women’s broader restriction from public life, we know the names of relatively few women artists who labored in royal courts or bureaucracies. Nonetheless, Curationist’s partner institutions hold some impressive examples of the craft of unsung women.

Mughal Court Artists: Sahifa Banu and Nini

While historical evidence is scant, there are some paintings both of and by women artists that testify to women’s role in the creative life of precolonial Indian courts. Indian women artists typically labored alongside their male relatives in workshop settings. Scholars speculate that they were often relegated to tasks like grinding pigments, making them less visible in the historical record.4

Some 17th- and 18th-century paintings show the ladies of royal zenanas, or palace women’s quarters, making art. For example, Dhanasri Ragini is part of a ragamala series of paintings personifying musical scales (ragas and raginis), with raginis often taking the form of beautiful women. The painting shows a woman drawing while her companion looks on. Art historians attribute the painting to the Rajput court at either Bundi or Ragogarh.5

Art historians also know the names of a handful of women painters who produced beautiful artworks, primarily miniature paintings, in the zenanas of the Mughal court.6 Sahifa Banu was active during the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir. An inscription on the back of a portrait of Shah Tahmasp of Iran attributes the painting to Sahifa Banu.7 Based on stylistic comparisons, art historians have attributed The Son Who Mourned His Father, featured here, to her as well. The painting illustrates a scene from one of the tales within the Mantiq al-Tair, a Persian cycle of stories-within-stories.8

Sahifa Banu, The Son Who Mourned His Father, ca. 1620. Aga Khan Museum, CC BY-NC.

Art historians believe that Sahifa Banu based her version of The Son Who Mourned His Father on Funeral Profession, pictured here, from a late 15th-century Persian Mantiq al-Tair manuscript. They speculate that a copy of the manuscript must have made its way to the Mughal capital. This reference, alongside the sophistication of Sahifa Banu’s work, indicates the high level of artistic and cultural education she had access to at court.

The work of another woman artist, Nini, similarly testifies to the expansive cultural influences in the Mughal court. Nini painted a delicate rendering of a European engraving of the Christian Saint Cecilia, by Hieronymus Wierix. The Wierix print is included above. Nini’s Saint Cecilia is currently held in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Mughals and their court artists collected and often made studies of European art, which Jesuit missionaries brought to the subcontinent. In this example, Nini, who signed the painting, transforms the somber Hieronymus Wierix print of the martyrdom of Saint Cecilia into a lyrical celebration of Persianate poetic love.9

Acllacona Weavers in Incan State Workshops

Rulers of what is now called the Inca Empire sponsored large-scale production of textiles and ceramics in imperial workshops. They distributed the textiles to elites in the societies they conquered. Specific designs indicated status and loyalty to the Inca imperial power.10 The imperial center collected cloth as tribute from those they ruled. Rulers also gifted ceramic plates and jars to attendants at large state feasts, an act that demonstrated imperial largesse and cemented social relationships.11

Spanish colonizers devastated indigenous Andean societies, including local knowledge systems, so it’s hard to identify whether women made specific works.12 However, archeological evidence, texts from early colonial Peru—including the writings of Inca chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala—and Indigenous Andean women’s continued textile art tell us that women occupied a key role in imperial weaving and ceramic production.13

Poma de Ayala translated the term for “married woman,” ahuacoc huarmi, into Spanish as texedora, or weaver. Married women wove cloth for their households as well as for Inca noblemen and military leaders. Additionally, the government recruited some girls to serve as aclla or acllacona, women who made textiles full time for the empire. Alongside cloth, they were responsible for making chicha, or maize beer, for rituals. Some acllacona were ritually sacrificed; others were married to Inca noblemen; still others remained single and were expected to be celibate for life.14 A second, male group, the cumbicamayoc, also wove for the state. Art historians disagree on whether the two gendered groups specialized in different kinds of weaving.15

Here, we include an elaborately crafted tunic, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The object’s publicly listed provenance begins with a 1982 sale at Sotheby’s, so we can’t trace its full journey from the Andes to the New York City museum. We also can’t say for certain the gender of the person who made the tunic. However, Met curator Joanne Pilsbury and conservator Christine Giuntini describe the aclla system in providing context for the tunic. They note that creases on the garment indicate its owner likely folded it and kept it in a stone box as a marker of the garment’s preciousness. Viewers can thus imagine the paths through which this kind of luxury textile might have traveled, from an imperial textile workshop that included women weavers, to an elite Incan owner, and eventually to the Met.16

Many Indigenous Andean women continue textile practices today, using motifs and language directly descended from precolonial art.17

French Salon Painters: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Anne Vallayer-Coster, and Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

In the 18th century, Paris was the center of the European art world. Despite social suspicion of women’s cultural and political power, some French women artists gained unprecedented prominence.18 We’ll focus on three of them, who regularly exhibited paintings in the famous Salons: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Anne Vallayer-Coster, and Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. They all received patronage from royal women; Marie Antoinette herself patronized Labille-Guiard and Vallayer-Coster.19

Anne Vallayer-Coster painted a number of still lifes, including Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell. Philosopher and critic Denis Diderot, Vallayer-Coster’s contemporary, praised her work. “No one of the French school can rival the strength of [Vallayer-Coster’s] colors, nor her uncomplicated surface finish,” the critic wrote in 1791.20

Portraits were immensely popular, and some women achieved great fame in the genre. Anne Vallayer-Coster painted a few portraits of Marie Antoinette. In recognition of Vallayer-Coster’s talent, Marie Antoinette gave her the title of “Painter to the Queen.”21

Another woman artist, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun, became a celebrity, navigating the ever-changing tides of court favor and intrigue. Her portraits idealized the queen as a blushing mother wearing frothy gowns in lavish Romantic and classical settings.

Le Brun painted her own portrait as well. At that time in France, it was considered scandalous for women to display their paintings in public, akin to the display of their flesh.22 Critics scolded Le Brun in 1786 for a self-portrait with her child in which she smiled with teeth.23

In another work, Le Brun painted her daughter looking into a mirror, allowing her to present the child’s face both in profile and gazing directly at the audience. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art website states, Le Brun’s painting of her child was “a tacit nod to the fact that her ability to create encompassed but was not limited to motherhood.”24

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard painted numerous portraits. She also advocated for women’s access to art training.25 At the time, senior painters (almost all male) regularly refused women apprentices. In contrast, Labille-Guiard painted herself in her studio flanked by two women students.

When French revolutionaries overthrew the royal family, Labille-Guiard and Le Brun fled France; both would return to reestablish their painting careers several years later.26 Vallayer-Coster remained through the Revolution, gaining enough favor to exhibit a portrait of Robespierre at the 1791 Revolutionary Salon. She even proposed a painting school for women. She fell out of favor, however, and while she survived the Reign of Terror, her career never fully recovered.27

Chinese Literati: Chen Shu and Guan Daosheng

In Imperial China, literati or scholar-official painters were members of the elite bureaucratic class who painted for pleasure. They typically considered their work superior to that of court painters laboring in imperial workshops. Scholar-officials often had funded government posts and painted as hobbyists. Much of their work was not directly commissioned by the ruler in a workshop setting. Yet because of their bureaucratic positions, their art was closely tied to state power.28

Some modern scholars argue that the literati emphasis on amateur painting enabled some women artists in their social milieu to succeed, as their families felt painting was an appropriately feminine hobby. Painter fathers and husbands often trained their female relatives in the course of imparting gendered social graces. Some courtesans, too, became renowned painters.29

Guan Daosheng was a calligrapher, painter, and poet. She lived at the Yuan court alongside her husband, renowned artist and calligrapher Zhao Mengfu.30 The emperor patronized Guan Daosheng’s work.31 Guan Daosheng’s contemporaries critiqued her for using a style they considered inappropriately masculine.32 She responded defiantly: “To play with brush and ink is a masculine sort of thing to do, yet I made this painting. Wouldn’t someone say that I have transgressed? How despicable, how despicable.”33

Chen Shu is widely considered the first female painter of the Qing dynasty.34 She received education in painting as a child, and married into a prominent scholar-official family. Her son became a favorite of the Qianlong Emperor, and advocated for his mother so that eventually the Emperor patronized her work.35

Conclusion

While women artists have often been excluded from the formal records of states and empires, the details of their work that do exist testify to their cultural and political power. In their art, women helped to create, and sometimes critique, the public value systems of kingdoms and empires. Their works can help contemporary viewers better understand the relationship between gender, visual culture, and political power—categories that remain salient today.

This feature is the third installment in Curationist’s seven-part series on women artists in our partner archives. For a guide to the series, see the introduction, "Women Artists and the Museum." For the previous piece in the series, see "Women Artists Representing the Divine." For the next piece in the series, see "Women Artists: Sovereignty, Kinship, and Care" (to be published in April 2024).

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Suggested Readings

“5 Women Artists of the Mughal Court.” The Heritage Lab, 2 March 2021.

Auricchio, Laura. “Eighteenth-Century Women Painters in France.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004.

Ghazi, Ghazal. “Unraveling ‘Ishq: Love in the Poetry, Miniature Painting, and Calligraphy of the Persianate World.” Library of Congress, 2022.

McHugh, Julia. “Andean Textiles.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Weidner, Marsha. Views from the Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists, 1300-1912. Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1988.

Citations

Sinha, Gayatri. “Women Artists in India: Practice and Patronage.” In Deborah Cherry and Janice Helland, eds. Local/Global: Women Artists in the Nineteenth Century. Ashgate, 2006, pp. 60-61.

There are numerous in-depth studies of authorship in various court painting traditions. Persian: Roxburgh, David J. “Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting.” Muqarnas vol. 17, 2000, pp. 119–146, https://web.archive.org/web/20161021084120id_/http://archnet.org/system/publications/contents/5128/original/DPC1861.pdf?1384788408. Accessed 28 April 2023. Northern European: Grimm, Clause. “Authenticity and Authorship.” Lorenzelli, Jacopo and Eckard Lingenauber, eds. The Lure Of Still Life. Galerie Lingenauber, 1995, http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/4197/1/Grimm_Authenticity_and_authorship_1995.pdf. The Kingdom of Benin: “Itan Edo.” Digital Benin, https://digitalbenin.org/itan-edo. Accessed 28 April 2023. Maya: Houston, Stephen. “Crafting Credit: Authorship Among Classic Maya Painters and Sculptors.” In Costin, Cathy Lynn, ed. Making Value, Making Meaning: Techné in the Pre-Columbian World. Harvard University Press, 2016, https://www.academia.edu/36849147/Crafting_Credit_Authorship_among_Classic_Maya_Painters_and_Sculptors.

Strunck, Christina. “Female Court Artists: Women’s Career Strategies in the Courts of the Early Modern Period.” In Jones, T.L., ed. Women Artists in the Early Modern Courts of Europe: c. 1450–1700. Amsterdam University Press, 2021, pp. 54, https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048540228.002. Accessed 27 February 2024.

“Women Artists in India: Practice and Patronage,” pp. 61.

“Women Artists in India: Practice and Patronage,” pp. 60.

“5 Women Artists of the Mughal Court.” The Heritage Lab, 2 March 2021, https://www.theheritagelab.in/women-artists-mughal-court/. Accessed 11 September 2022.

“Shah Tahmasp of Iran.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O405633/shah-tahmasp-of-iran-painting-sahifa-banu/. Accessed 12 March 2024.

“The Son Who Mourned His Father.” Aga Khan Museum, https://www.agakhanmuseum.org/collection/artifact/the-son-who-mourned-his-father-akm206. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Natif, Mika. “Mughal Masters and European Art: Tradition and Innovation at the Royal Workshops.” In Mughal Occidentalism. Brill, 2018, pp 85-88, https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/ebk01:4100000005601893. Accessed 28 April 2023. For love in the poetry and painting of the Persianate world, see: Ghazi, Ghazal. “Unraveling ‘Ishq: Love in the Poetry, Miniature Painting, and Calligraphy of the Persianate World.” Library of Congress, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=ad7341e261ed4d9ea29e9be58c0590d4&bookmark=Introduction.

McHugh, Julia. “Andean Textiles.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/adtx/hd_adtx.htm. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Costin, Cathy. “Gender and Status in Inca Textile and Ceramic Craft Production.” The Oxford Handbook of the Incas, Sonia Alconini and Alan Convey, eds. Oxford University Press, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190219352.013.14. Accessed 25 April 2023.

Historians estimate that between 1520 and 1570, Spanish colonizers’ violence and disease killed seven to nine million Andean people, reducing the population from between 10 and 12 million people to 3 million people. See: “Spanish Conquest of the Inca Empire.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_conquest_of_the_Inca_Empire#Effects_of_the_conquest_on_the_people_of_Peru. Accessed 31 May 2023.

“Gender and Status in Inca Textile and Ceramic Craft Production.”

Costin, Cathy Lynne. “Housewives, Chosen Women, Skilled Men: Cloth Production and Social Identity in the Late Prehispanic Andes.” Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, vol. 8, no. 1, January 1998, https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/ap3a.1998.8.1.123. Accessed 31 May 2023.

“Gender and Status in Inca Textile and Ceramic Craft Production.”

Pilsbury, Christine and Christine Giuntini. “Tunic with Diamond Band.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314528. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Meisch, Lynne A. “Messages from the Past: An Unbroken Inca Weaving Tradition in Northern Peru.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2006, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1344&context=tsaconf. Accessed 12 March 2024.

Hyde, Melissa and Jennifer Dawn Milam, eds. Women, Art, and the Politics of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Taylor and Francis, 2017.

Auricchio, Laura. “Eighteenth-Century Women Painters in France.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/18wa/hd_18wa.htm. Accessed 17 August 2022.

Smee, Sebastian. “This Painting of Plums is Perfection.” The Washington Post, 15 December 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/interactive/2021/anne-vallayer-coster-basket-of-plums/. Accessed 12 March 2024.

“This Painting of Plums is Perfection.”

“Eighteenth-Century Women Painters in France.”

“Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89lisabeth_Vig%C3%A9e_Le_Brun. Accessed 28 April 2023.

“Julie Le Brun (1780–1819) Looking in a Mirror.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438132. Accessed 31 January 2024.

“Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad%C3%A9la%C3%AFde_Labille-Guiard. Accessed 31 January 2023.

“Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.” “Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.”

“Eighteenth-Century Women Painters in France.”

Department of Asian Art. “Scholar-Officials of China.” In The Heilbrunn History of Art Timeline, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/schg/hd_schg.htm. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Weidner, Marsha. Views from the Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists, 1300-1912. Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1988, pp. 13, https://archive.org/details/viewsfromjadeter00weid/page/12/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 12 March 2024.

“Guan Daosheng.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guan_Daosheng. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Views from the Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists, 1300-1912, pp. 66–67.

Kwong, Charles Yim-tze. “Guan Daosheng.” In Kang-i Sun Chang and Haun Saussy, eds. Women Writers of Traditional China: An Anthology of Poetry and Criticism, Stanford University Press, 1999, pp. 126–130, https://archive.org/details/womenwritersoftr0000unse. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Colville, Alex. “Guan Daosheng, the woman who conquered Yuan art.” Sup China, 7 September 2020, https://thechinaproject.com/2020/09/07/guan-daosheng-the-woman-who-conquered-yuan-art/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Chen Shu (painter).” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chen_Shu_(painter). Accessed 27 October 2022.

Views from the Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists, 1300-1912, pp. 25.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.