Chinese Landscape Painting: At the Orchid Pavilion

By Reina Gattuso•January 2023•13 Minute Read

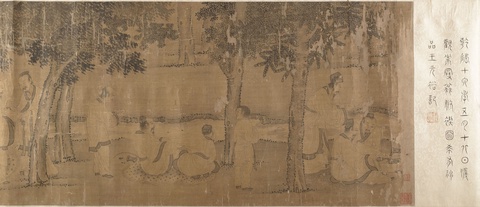

Formerly attributed to Li Gonglin (傳)李公麟 (ca. 1049–1106), Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion, 16th–17th century. Smithsonian Institution.

Landscape painting was one of the most prized art forms in imperial China. Scholar-artists typically painted with brush and ink, combining meditative landscapes with poetry and calligraphy.

Introduction

In the year 353 CE, a group of erudite men met at a mountain pavilion in China to celebrate the spring purification festival. A government official and famous calligrapher named Wang Xizhi convened the gathering. Like Wang, the attendees were scholar-officials, which modern-day English-speaking scholars call literati. These men (literati were almost all men) were usually members of an elite bureaucratic class who valued moral and aesthetic refinement.1 Attendees drank wine and composed poems. By the end of the evening, they had written 37. The literati immortalized their work in an anthology, and Wang Xizhi wrote the preface.2

The historic gathering at the Orchid Pavilion has been an important theme in Chinese art and literature ever since. While Wang Xizhi’s original calligraphy has been lost, the preface survived in stone engravings, most notably the Dingwu edition. British and French troops destroyed that engraving, kept in the imperial garden at Yuanmingyuan, during the Second Opium War. But rubbings from the Dingwu edition provided historical artists and contemporary scholars alike valuable source material.3

The Orchid Pavilion became especially important in shanshui, a kind of Chinese landscape painting. Shanshui literally means “mountain and water,” naming natural features that such painters commonly represent.4 Shanshui painters typically use a brush with ink and paint on silk or paper. These are the same materials used in calligraphy.5 Indeed, literati considered painting, poetry, and calligraphy the “three perfections.” Artists often combined these forms in shanshui, inscribing poems inspired by natural scenery on top of landscape paintings.6

Shanshui works often have political and spiritual connotations. Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, China’s three most important systems of belief, all revere the natural world.7 Daoist immortals were believed to occupy garden paradises, and Buddhist and Daoist temples were often built in rural settings.8 Starting in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), literati artists made landscape paintings that reflected their desire to escape cities and their official duties, to seek peace in the countryside.9

Shanshui painters, like other Chinese literati artists, learned their discipline primarily by copying previous painters rather than working from direct observation.10 Artists returned to the theme of the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion again and again as the medium developed. At various points in Chinese history, painters opted to emulate or revise previous works and styles. These revisions of a classic scene tell us about the contemporary moment—both the painter’s era and, by reflecting on our impressions and interpretations as viewers, our own.

Li Gonglin

Li Gonglin was a literati painter during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127 CE). He was famous for his paintings of horses as well as shanshui paintings and Buddhist and Daoist themes.11 One of his surviving works, a scroll illustrating the Confucian Classic of Filial Piety, argues that duty to family is harmony with the world at large.12

Turmoil and Transition During the Northern Song

The Northern Song Dynasty was a time of political and cultural turmoil. Early in the dynasty, many literati painters fled to the countryside, where they created landscape paintings that reflected their ideals of properly ordered human, social, and political hierarchy. Vast mountains, towering over trees and human figures, could represent the lofty stature of rulers watching over their subjects.

Artists in the newly formed Imperial Painting Academy borrowed this emphasis on landscape, transforming natural features into metaphors for a “perfectly ordered state.”13

Unknown (China), _Painting of the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion during the Spring Purification Festival (兰亭修禊图), 1781. Library of Congress, unrestricted.

Subsequent Song literati initiated a sea change in Chinese art as they rebelled against this imperial style and advocated for painting as a form of personal expression rather than courtly service.14 Li Gonglin and other literati painters began to prize spontaneity and a natural or untutored quality over professionalism.15 They valued the quality of the line in both painting and calligraphy as an expression of the painters’ personality and feelings about the subject matter rather than, in the case of painting, a literal representation of the subject itself.16 Shanshui paintings thus became representations of inner landscapes as much as outer ones.

The Culture of Copying

Seven hundred years after Wang Xizhi wrote the original preface, Li Gonglin painted the Orchid Pavilion Gathering in the painting Liu shang tu, “The Floating Goblets.” The image illustrated goblets full of wine floating down the river at the famous fete. That painting survives in the form of a copy commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor some six centuries later.17 The vast gaps between these acts of creation demonstrate the longevity of cultural transmission.

Because of this emphasis on copying as a tool for appreciation and pedagogy, however, correctly dating and attributing Chinese landscape paintings can be difficult. Art historians use details like brush strokes and the seals of artists and previous owners. Yet these can all be convincingly forged.18

Nevertheless, copies reveal the values of the copier’s time as well as provide valuable documentation of the original creator’s style. In 1560, for example, literati Qian Gu based his painting of the Orchid Pavilion Gathering on a composition by Li Gonglin.19 Qian Gu worked during the Ming Dynasty, which art historians characterize as a time when artists sought inspiration in Chinese cultures of the past.20 Qian Gu’s reproduction of Li Gonglin’s Orchid Pavilion Gathering can thus be seen as an attempt at artistic restoration.

By copying Li Gonglin’s work, particularly the ancient Orchid Pavilion theme, artists demonstrated a reverence for Chinese literary precedent. And by replicating past masters’ brushstrokes, painters internalized an expressive language that allowed them to be spontaneous while still nominating themselves to a great artistic tradition.

Zhao Mengfu

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE), China became part of the immense Mongol Empire. Since the Mongols were the first non-ethnic-Han people to rule the Chinese Empire, they shored up their legitimacy by gradually adopting Chinese models of statecraft and imperial culture.21

Still, Mongol administrators pushed aside local scholar-officials. Many Song Dynasty loyalists withdrew from public life to seek solace in artmaking and spirituality. The literati painters of the time deepened their predecessors’ emphasis on landscape painting as an expression of the internal self.22

During this time, literati artist Zhao Mengfu developed a new style of bold brushwork that art historians credit with helping establish modern Chinese landscape painting.23 He was an official in the Yuan court renowned for his combination of landscape painting and calligraphy, which also informed his brushwork.

Zhao Mengfu refined his calligraphy through assiduous copying of rubbings of the Dingwu copy of The Orchid Pavilion Preface.24 His freehand copy of the Preface still exists, providing insight into how he incorporated the seminal text into the development of his unique calligraphic and painterly style.

Zhao Mengfu was married to Guan Daosheng, also a highly respected painter, calligrapher, and poet.

Zhao Mengfu integrated calligraphic brushstrokes into his painting. In his work Twin Pines, Level Distance, Zhao Mengfu used cursive script conventions to describe the rocks and seal script style to outline the trees. Pines symbolize survival in Chinese art, and art historians posit that the artist meant to represent his own and his culture’s survival in the Mongol court.25

The calligraphic quality of Zhao Mengfu’s work provides a primer on how to view Chinese scroll paintings. They are meant to be “read” from right to left, like a written Chinese text.26 The landscape literally unfurls as the viewer opens the scroll. The viewer thus replicates the experience of meandering through both a literal and psychic landscape.27 They may discover towering mountains and misty valleys, and stumble across humorous or creative details.

Subsequent artists painted the Orchid Pavilion Gathering in the style of Zhao Mengfu. We can see his influence in, for example, the shapes of trees. By painting this classic scene in Zhao’s style, the Ming- or Qing-era artist evoked both continuity and stylistic innovation.

Tang Yin

After the fall of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, the Han rulers of the Ming court took a decisive role in dictating artistic styles, seeing themselves as restoring Chinese culture.28

Amid this reinstated orthodoxy, painter Tang Yin was considered both a master and a rebel. He was banned from taking the civil service exams based on accusations of cheating, and sustained himself through his art. Some literati considered this professionalization vulgar.29

Tang was known for paintings of beautiful women as well as landscapes. His Scholar-Hermits in the Autumn Mountains is an excellent example of the experience of meandering through a scroll. The work depicts a river lazily flowing past lofty mountain peaks dotted with autumnal trees. Scholar-hermits sit playing a game; workers fish the river, a common motif.30

Tang Yin used blank silk to depict water, distant sky, and mist hiding the tops of the mountains. His sparing use of color, with orange leaves and a preponderance of green hues, evokes the blue-green style of shanshui.

A later artist, likely from the 17th to 19th centuries, copied Tang Yin’s rendition of the Orchid Pavilion Gathering. The depiction of ample water flowing through the hills of a paradisal scholar-recluse’s landscape evokes Tang’s work.

Modern and Contemporary Chinese Landscape Painting

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed significant change in Chinese landscape painting. Toward the end of the Qing Dynasty, imperial forces, under pressure from Western powers, undertook a project of economic and military modernization.31 The invention of photography had a profound impact on Chinese painting, as it did on other traditions, revolutionizing the relationship between artistic representation and the visual world.32

This sense of innovation continued through the advent of the Chinese Republic. With increased exposure to European art, Chinese artists like Qi Baishi and Tao Lengyue created landscapes that experimented with techniques like chiaroscuro and modernist movements like Cubism.33

Following the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949, many painters turned to peasant agricultural subjects. Both socialist realist oil painting and traditional ink painting, adapted to communist themes, were popular.34 During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, the government deemed many traditional artistic forms, such as landscape painting, counterrevolutionary remnants of a premodern, elitist culture.35 Many artists were incarcerated or had their work destroyed.36 This occurred against the background of mass, largely state-sponsored violence that killed an estimated 1.6 million people.37

Changing cultural policies in the late 20th century enabled more open exploration of both traditional and contemporary forms. Artists who had done agricultural labor in “re-education” camps included rural and peasant motifs in their art.38 Artists combined techniques and tropes from traditional shanshui painting, socialist realism, and European art to create works of social and political commentary.39 Others revitalized traditional scholar painting in unexpected ways. For example, Xu Lele and other artists of the New Scholar School offer a playful take on literati themes, such as the lone scholar in a landscape.

Meanwhile, Te Wei’s 1988 animated film Feelings from Mountain and Water takes its name from the literal meaning of shanshui. Te Wei animates a traditional ink landscape painting. He uses calligraphic lines to tell a narrative about an elderly recluse-scholar and his young student. The resulting short film brings the traditional scroll painting to life. Feelings from Mountain and Water invites viewers to take a physical, psychic, and historical meander through Chinese landscape painting.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

“Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/48901. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Orchid Pavilion Gathering.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orchid_Pavilion_Gathering. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Painting of the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion during the Spring Purification Festival.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021666445/. Accessed 30 August 2022.

Shan Shui Projects, https://www.shanshuiprojects.net/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Writing Brush.” China Culture, http://en.chinaculture.org/library/2008-01/24/content_44518.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Shan Shui.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shan_shui. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Palmer, Martin. “Daoism, Confucianism, and the Environment.” China Dialogue, 15 November 2013, https://chinadialogue.net/en/nature/6502-daoism-confucianism-and-the-environment/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Chinese Gardens: Pavilions, Studios, Retreats.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/chinese-gardens. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Landscape Painting in Chinese Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Yu, Shuishan. Writing an Image: Chinese Literati Art. Oakland University Art Gallery, November 2009, https://our.oakland.edu/bitstream/handle/10323/3876/Chinesecatalog.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Li Gonglin.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Gonglin. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“The Classic of Filial Piety.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39895. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Northern Song Dynasty.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nsong/hd_nsong.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Northern Song Dynasty.”

“Northern Song Dynasty.”

Writing an Image: Chinese Literati Art.

“Painting of the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion during the Spring Purification Festival.”

Smith, Judith G. and Wen C. Fong, eds. Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Painting. Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Issues_of_Authenticity_in_Chinese_Painti/maSlNPZu_hkC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion.”

“Ming Dynasty.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ming/hd_ming.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Yuan Dynasty.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/yuan/hd_yuan.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Yuan Dynasty.”

“Zhao Mengfu.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhao_Mengfu. Accessed 27 July 2022.

McCausland, Shane. Zhao Mengfu. Hong Kong University Press, 2011, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Zhao_Mengfu/L2yyJbWQ67cC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=dingwu. Accessed 30 August 2022.

“Twin Pines, Level Distance.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/40508. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Why Some Languages Are Written Right to Left.” Thesaurus.com, 11 March 2012, https://www.thesaurus.com/e/writing/righttoleft/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

How to “Read” A Chinese Scroll, Freer/Sackler Education, 2016, https://asia.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/chinese-scroll-lesson.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Ming Dynasty.”

“Tang Yin.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tang_Yin. Accessed 30 August 2022.

“Scholar-Hermits in the Autumn Mountains.” The Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1976.94. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Mitter, Rana. “The Era of Modernization in China Part One: Fall of the Qing Dynasty.” Facing History and Ourselves, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/era-modernization-china-part-one-fall-qing-dynasty. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“Man on a Bridge.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49462. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Lee Tzu-Tung. “The Transformation of Modern Chinese Landscape Painting.” New Bloom Mag, October 2015, https://newbloommag.net/2015/10/31/shanshui-politics-eng/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

“The Art of China’s Cultural Revolution.” Johnson Museum of Art, https://museum.cornell.edu/exhibitions/art-chinas-cultural-revolution. Accessed 30 August 2022.

“Art and China’s Revolution.” Asia Society, https://asiasociety.org/art-and-chinas-revolution. Accessed 30 August 2022. See also: Sorace, Christian. “Aesthetics.” Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubrere, eds. Afterlives of Chinese Communism, Australia National University Press and Verso, 2019, pp. 11-16, http://doi.org/10.22459/ACC.2019. Accessed 30 August 2022; Thornton, Patricia M. “Cultural Revolution.” Afterlives of Chinese Communism, pp. 55-61.

Andrews, Julia F. “The Cultural Revolution.” Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979, University of California Press, 1995, https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft6w1007nt&chunk.id=d0e10324&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e10324&brand=ucpress. Accessed 27 July 2022.

De Witte, Melissa. “China’s Cultural Revolution was a power grab from within the government, not from without, Stanford sociologist finds.” Stanford News, 29 October 2019, https://news.stanford.edu/2019/10/29/violence-unfolded-chinas-cultural-revolution/. Accessed 30 August 2022. See also: Yongyi Song. “Chronology of Mass Killing During the Chinese Cultural Revolution.” Mass Violence and Resistance Research Network, 25 August 2011, https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/chronology-mass-killings-during-chinese-cultural-revolution-1966-1976.htm. Accessed 30 August 2022.

”Modern and Contemporary Chinese Art.” Williams College Museum of Art, https://artmuseum.williams.edu/collection/modern-contemporary-chinese-art/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

”Modern and Contemporary Chinese Art.”

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.