Women’s Reflections in Renaissance and Modern European Painting

By Reina Gattuso•July 2022•11 Minute Read

Berthe Morisot, Woman at Her Toilette, 1875/80. Art Institute of Chicago. Berthe Morisot painted bourgeois women with a soft sensuality, employing wispy, cool brushstrokes.

Renaissance and modern European artists used mirrors in allegories of vanity, ephemerality, and the illusion of art. They associated mirrors with women, reflecting patriarchal beliefs about women’s “weak” moral character. Contemporary feminist and queer artists challenge this sexist symbolism, using mirrors to create self-portraits that demonstrate defiant self-possession.

Introduction

Artists in Europe—the majority of them male—have been fascinated with the pairing of women and mirrors for thousands of years. Ancient Greek and Etruscan craftspeople often decorated mirrors with engravings of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, artists painted women in front of mirrors as allegories of beauty but also of sinful lust, vanity, and the transience of earthly desire.1

Their paintings reflect a sexist double standard. Male artists painted themselves as active creators. They used mirrors as an optical trick, displaying their virtuosity and evoking contemporary scientific advances.2 In contrast, male artists painted women as objects of desire and moral censure. The (male) viewer is presumed to take pleasure from these images, while the women depicted are condemned for the sin of lust. In art historian John Berger’s words, these images reinforced the notion that “men act and women appear.”3

In contrast, since ancient times, women artists used mirrors in self-portraiture to take ownership of their own image. From the ancient Greek artist Iaia, who was said to use a mirror to paint herself, to contemporary feminists like Helen Chadwick, women and queer artists have incorporated mirrors into their art as a form of self-reflection and self-fashioning.

Mirror as Temptation

Renaissance European painters used mirrors as part of a complex symbolic language meant to remind the viewer that life and youth were transient. They associated women, whom Christian authorities taught were morally weak,4 with vain attempts to cling to earthly beauty.

In an oil painting by Dutch artist Gerard ter Borch, a young woman gazes at an elderly woman. The young woman’s back is to us, allowing the viewer to admire her long neck and bare shoulders. Her rich white gown and elaborate hairstyle contrast with the elder’s subdued dress and covered hair. The message: The young woman, too, will age.

In ter Borch’s painting, the mirror symbolizes the young woman’s attempt to hold on to beauty—all the while conveniently allowing the viewer to admire those same good looks. Ironically, painting allowed her beauty to survive for centuries in the hands of wealthy male owners.5

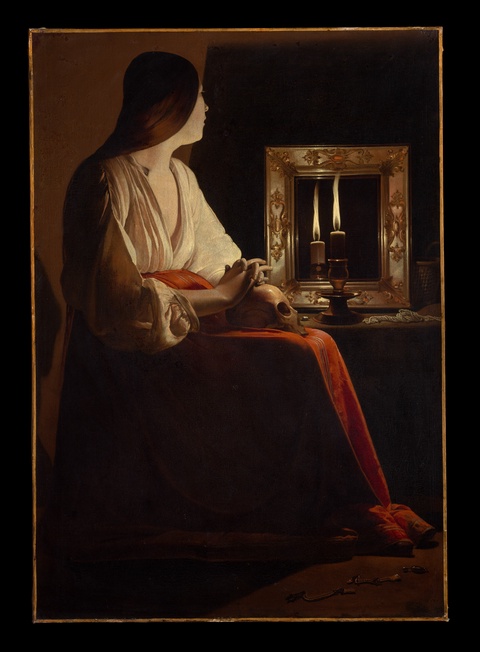

Artists used mirrors as symbols of sexual sin. French artist Georges de la Tour painted Mary Magdalene sitting in front of a mirror. Mary Magdalene was an apostle of Jesus Christ whom church leaders in the 6th century recast as a repentant sex worker. De la Tour used dramatic chiaroscuro to impart an intimate and somber atmosphere. Mary Magdalene turns away from the viewer in modesty or contemplation, her averted gaze indicating that she is no longer available for the viewer’s visual and sexual pleasure

In European paintings of the time, candles, like the one next to Mary Magdalene, symbolized spiritual wisdom. Skulls symbolized mortality, while the mirror represented vanity.6 Rather than seeing her face reflected in the mirror, we see the candle—indicating Mary has given up the vanity of the flesh for spiritual enlightenment.

A Flemish oil painting also warns viewers of the dangers of lust. It depicts a scene from a 16th century epic poem about a medieval Christian crusader named Rinaldo, whose army attempts to capture Jerusalem from Muslim rulers.7 Once there, a beautiful local sorceress, Armida, invites him to stay in her castle. Rinaldo becomes so distracted by sensual pleasures that he temporarily abandons his mission. In the painting, we see Armida and Rinaldo frozen as they gaze at Armida’s beauty in a mirror.8

The story was meant to warn readers away from worldly pleasures, lest they become “drunk with ease” and lose sight of their moral purpose.9 Yet if we decenter European Christianity, we can see Armida as a political protagonist, who used her sexual labor to literally disarm Rinaldo. Rinaldo is lost in pleasure—a much worthier pursuit than stealing someone’s land.

Mirror as Allegory of Art

Because of mirrors’ optical function, painters associated them with art itself. In the realist traditions of Renaissance Europe, comparing a painting to a mirror image must have been quite a compliment. At the same time, mirrors could imply that art was artifice, a mere reflection of the world, and thus untrue—just like women supposedly were.

In Caspar Netscher’s painting of a girl, the mirror evokes the uncanny illusionism of art. Netscher skillfully, realistically depicts the lustrous, rumpled silk of his subject’s dress. Yet the sitter’s gesture toward the mirror holds a warning: The painting is but a reflection of reality.10

Mirrors were frequently included in allegories of art, following an allegorical language codified in the late 16th century.11 One 18th century Italian painting personifies art as a woman holding a palette and paintbrushes. Rather than daubing a canvas, she contemplates herself in a mirror held up by a cherub.12 Her theatrical pose and the mask attached to her headdress characterize her as an embodiment of art’s vanity and illusion.

Some Renaissance women artists challenged the depiction of themselves as symbols of vanity and objects of the male gaze. In Self-Portrait as Allegory of Painting, Artemisia Gentileschi depicted herself as both artist and allegory. Her gender gave her a unique opportunity compared to male artists. She was not only a painter, but could identify with the allegory of painting herself.13 Her rolled-up sleeve indicates the physicality of her painting practice. The high angle, a very difficult view of oneself to render, demonstrates her formidable skill.

Mirrors and the Modern Woman

Industrialization transformed European life, including gender relations. In the 19th century, single women increasingly moved to cities for work, achieving a new level of mobility.14 Leisure and entertainment industries exploded. Suffragists asserted that women are rights-bearing individuals (while often ignoring or actively sabotaging the liberation of women of color and women in European colonies).

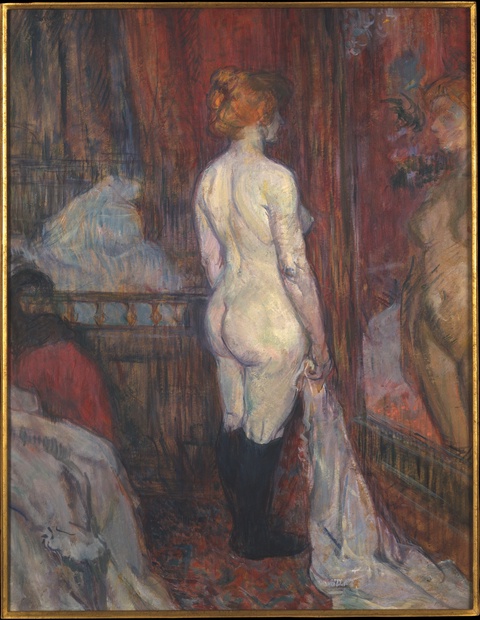

French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec depicted the raucous milieu of urban entertainers in his 1897 painting Woman Before a Mirror. Toulouse-Lautrec frequented brothels as both a client and friend, and painted sex workers’ daily lives and intimacies with one another, with what some queer and feminist critics see as empathy.15

In Woman Before a Mirror, a sex worker stares at her reflection in a moment of quiet contemplation. She turns her body away from the viewer. We’re still able to admire her back and buttocks. Yet her rapt gaze at herself, and distance from the viewer, suggest that we’ve found her in a rare private moment, when she needn’t perform her sexuality for a spectator. The woman holds her head high, but her shoulders droop slightly—this is, after all, her workplace.

Another painting, by French Impressionist Berthe Morisot, similarly shows a woman contemplating her appearance in a mirror. Like fellow woman impressionist Mary Cassat, Morisot frequently painted the bourgeois interiors she occupied, reflecting her gender and elite class.

Morisot’s frothy brush strokes detailing lace and flower petals, and the white, periwinkle, and lavender tones, imbue the scene with delicate sensuality. The woman’s dress strap slips down her shoulder, inviting viewers to look at her back. Yet in this domestic, feminized space, we see the woman with a homoerotic gaze, as an intimate female friend or lover might see her. We can’t see her image in the mirror, but she can see herself—and that is more important.

A woman’s bold, direct gaze into the mirror could evoke modernity and independence. In the 1890s, U.S. artist and socialite Alice Pike Barney, who spent part of her career in Paris, painted Alice Roosevelt Longworth. The daughter of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, Longworth was a media sensation for her brash comportment, which challenged the mores for elite women at the time. Barney paints Longworth as the quintessential New Woman, the swirling pastels of her stylish slim-cut gown and flowered hat contrasting with the frank self-assuredness of her gaze in the mirror. Her dress is an icy azure known as Alice Blue. The color became a trend among women participating in the era’s increasingly commercialized urban culture.17

Mirrors in Contemporary Feminist and Queer Art

In the 20th and early 21st centuries, feminist and queer artists continued to subvert the mirror trope. They challenged the binary, as stated by Berger, between “acting” and “appearing,” and recast themselves as active creators and curators of their own image.

In Interwar Europe, amid increasing accessibility of photography and women’s participation in a bustling public life, women photographers created work commenting on the strictures of feminine performance. German Jewish photographer Ilse Bing photographed herself in the mirror alongside her Kodak, reframing and reclaiming women’s gaze through the technological lens of the camera. German Jewish duo Grete Stern and Ellen Rosenberg Auerbach, known as Ringl and Pit, came from both advertising and avante garde backgrounds. They produced work, such as Eckstein with Lipstick, that used mirrors to probe the commodification of beauty.18

In the early 21st century, contemporary LGBTQ artists have used mirrors to depict queer and gender-expansive experiences. In The Bar on East 19th, painter Salman Toor remixes Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère to center a queer bartender of color. The bartender meets the viewer’s eye—and, by extension, their patron’s or suitor’s—with a gaze both sweet and subtly defiant. Photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya also uses mirrors in his photography. Many of his photographs show reflections of naked bodies in studio mirrors. His photograph Figure (0X5A0918) shows a reflection of two Black people tenderly intertwined. The work portrays “the entanglement of friendship and desire” in queer intimacy.19

Curators at the U.K.’s National Portrait Gallery dubbed a major 2001 exhibition of women’s self-portraits “Mirror Mirror.” The show included British artist Helen Chadwick’s Vanitas II. Chadwick photographed herself naked from the waist up, arm slung around a mirror that reflects her own image and artworks. Lush fabrics invoke the boudoir. Chadwick’s gesture of embrace, her intent gaze at herself, and the way the tip of her nipple touches its own reflection in the cool glass, are autoerotic.20 In subverting patriarchal power dynamics related to the gaze, artists like Bing, Toor, Sepuya, and Chadwick hold a mirror to society.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

Wallentine, Anne. Art UK, 14 January 2022, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/reflections-on-the-mirror-in-art. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Warwick, Genevieve. “Looking in the Mirror of Renaissance Art.” Art History, vol. 39, no. 2, April 2016. Academia.edu, https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/73395639/Warwick_2016_Art_History-with-cover-page-v2.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. BBC and Penguin Books, 1972. Monoskop, https://monoskop.org/images/9/9e/Berger_John_Ways_of_Seeing.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Nash, Jerry C. “Renaissance Misogyny, Biblical Feminism, and Hélisenne de Crenne's Epistres Familieres et Invectives.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 2, summer 1997, pp. 379-410. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3039184. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Woman at a Mirror.” Rijksmuseum, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-4039. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“The Penitent Magdalen.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436839. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Jerusalem Delivered.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerusalem_Delivered. Accessed 27 June 2022.

“Rinaldo and Armida in the Enchanted Garden.” The Walters, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/15439/rinaldo-and-armida-in-the-enchanted-garden/. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Rinaldo and Armida in the Enchanted Garden.”

“Girl Standing before a Mirror.” Art Institute of Chicago, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/16539/girl-standing-before-a-mirror. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Cesare Ripa.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesare_Ripa. Accessed 27 June 2022.

“Allegory of Painting.” The Walters, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/20010/allegory-of-painting/. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura).” Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/405551/self-portrait-as-the-allegory-of-painting-la-pittura. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Moch, Leslie Page. “Internal migration before and during the Industrial Revolution: the case of France and Germany.” European History Online, 25 July 2011, http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/economic-migration/leslie-page-moch-internal-migration-before-and-during-the-industrial-revolution-the-case-of-france-and-germany. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Where are They Now? Toulouse-Lautrec’s study for In the Salon on the Rue des Moulins.” Hammer Museum, https://hammer.ucla.edu/blog/2017/09/where-are-they-now-toulouse-lautrecs-study-for-in-the-salon-on-the-rue-des-moulins. Accessed 25 May 2022. See also: “The Sofa.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437837. Accessed 25 May 2022.

“Alice Roosevelt Longworth.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Roosevelt_Longworth. Accessed 23 August 2022.

Brigham, Ann and Hana Layson. “Women on the Move: Gender and Mobility in American Culture, 1890-1950.” The Newberry, https://dcc.newberry.org/?p=14368. Accessed 23 August 2022.

O’Connor, John J. “Two Proto-Feminists Remember Weimar.” The New York Times, 6 February 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/02/06/arts/two-proto-feminists-remember-weimar.html. Accessed 23 August 2022.

“14 Artists on the Importance of Portraying Queer Love.” Artsy, 3 June 2020, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-14-artists-portraying-queer-love. Accessed 7 December 2022.

Jones, Jonathan. “Vanitas II, Helen Chadwick.” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/oct/13/arts.highereducation. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.