The Night Otherwise: Nocturnal Space in Japanese Edo Prints and Rājput Court Paintings

By Chrystel Oloukoï•August 2025•20 Minute Read

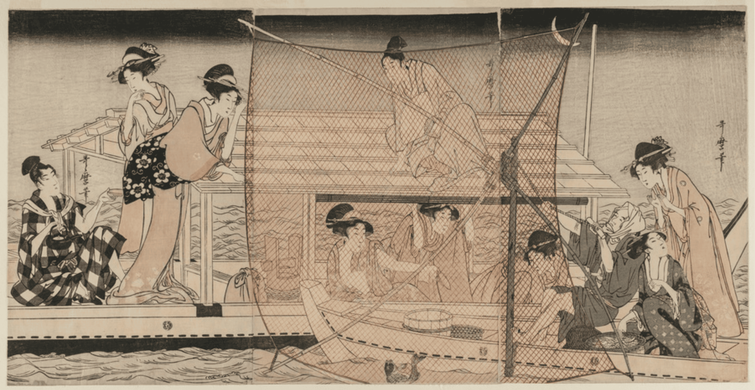

Kitagawa Utamaro (Japanese, ca. 1754–1806), Net Fishing at Night on the Sumida River, ca. 1800, Cleveland Museum of Art. CC0.

Societies perceive nighttime according to their particular social habits and cultural expectations. The work of Japanese Edo print artists and South Asian Rājput and Rajasthani miniature painters demonstrate two different nocturnal aspects: luminously realistic urban experiences and allegorical moods in courtly settings.

The global circulation of satellite imagery like this picture of “Earth at Night” shapes contemporary imaginations of night space. Progress comes to be associated with a constellation of cities with reliable lighting infrastructure, many of which are in the global North. Images of specks of light clustered amid vast regions of darkness starkly reproduce the contours of an unequal world order.

Satellite imagery, like any other type of visual representation, is not neutral. It inherits imperial ways of seeing1 and histories of positive valuations of light versus darkness that have a long genealogy in Western art and thought.2 Depictions of the night in particular, marked by profuse obscurity, have expressed not just literal nights but an existential and religious anguish about the human condition.3

In contrast to such tragic nocturnal atmospheres, Japanese Edo print artists and Rājput court painters presented a striking inverse perspective on the night. Woodblock prints crafted from outlines and flat washes, known as ukiyo-e, depict luminous night scenes in districts teeming with social, artistic, and economic activity. For Rājput miniature painters, darkness symbolized a complex range of feelings, for instance temerity, tenderness, love, and sorrow.

Societies of the Night, Arts of Entrapment

Both Rājput and Edo arts portray the night as a timescape of intense sociality. Their approaches, however, reveal distinct histories in relation to the forces of urbanization and their impact on their respective class milieus.

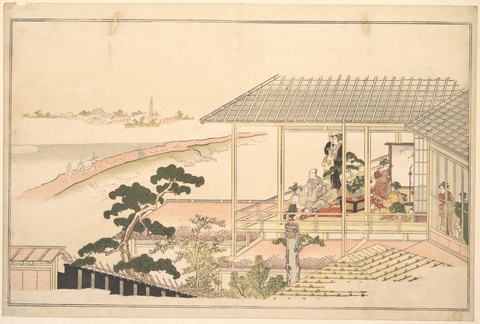

Japan’s rapid urbanization started in the early 17th century. The Edo period, from 1603 until 1868, witnessed the flourishing of the arts and changing social relations, crystallized around urban centers such as Edo (present-day Tokyo), the seat of the shogunate, as well as Osaka and Kyoto. Historians of urban Edo highlight the development of a widespread nighttime sociality. Art from the period aptly captures ordinary pleasures, such as viewing illuminated cherry blossoms, catching fireflies, partying in the moonlight, or boating on the Sumida River to escape the summer’s heat.4

In a triptych from around 1800, Net Fishing at Night on the Sumida River by Kitagawa Utamaro, two worlds collide: that of the fishermen whose net frames the scene, and that of the courtesans of the nearby licensed brothel district, Yoshiwara. The prominent net seems to ensnare fish and courtesans alike, as well as the fisherman’s legs. Both professions are arts of entrapment, in which the one casting the net is also at risk, at the mercy of the sea or the indenture system of the brothels. The nocturnal social worlds of the pleasure districts, Yoshiwara chief among them, supported the flourishing of many art forms, such as haiku poetry, ink calligraphy, bunraku and kabuki theatre.5 Among these are ukiyo-e prints or “pictures of the floating world,”6 a genre of woodblock printmaking featuring portraits of courtesans and ordinary people, as well as landscapes and weather studies. An art of layers, carving, inking, and pressure, ukiyo-e prints favored clear and bold outlines, with an often restrained use of color. In Net Fishing at Night on the Sumida River, only the net and some of the courtesans’ dresses are tinted in reddish hues, drawing focus, in a sea of soft and harsh greys. Only a thin band of dark ink at the top, alongside the moon, signals the nocturnal quality of the scene. This is a mere waning crescent moon, and yet the scene seems suffused with an unnatural luminosity.

The nocturnal social world of urban Edo Japan is embedded in the economic activity of ordinary people like fishermen and prostitutes. In contrast, the aristocratic Rājput world offers other forms of nighttime sociality, like that of the royal hunt.

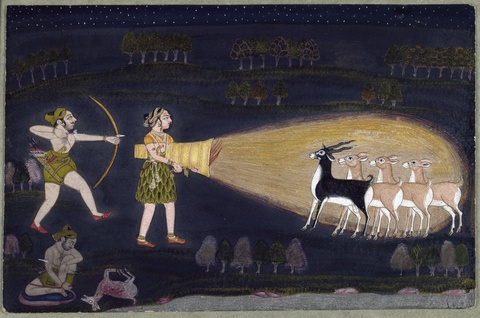

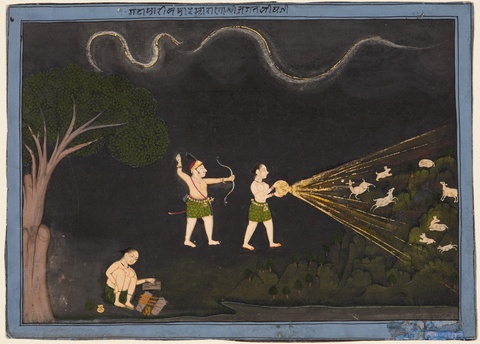

Depictions of royal hunts were a prolific genre, as they were a common pastime of the aristocratic Rājput courts, such as the Rājasthānī and Pahāri courts that many artists depended on for patronage from the 17th through the 19th century.7 In works such as Tiger Hunt of Raja Ram Singh II (unattributed, 1830–1840) or Jugarsi’s Maharana Jagat Singh II Hunting (1747), named and anonymous Rājput painters portrayed the complexity of nocturnal royal hunts, with their extensive entourage, set of traps, and prey that scampers in all directions.

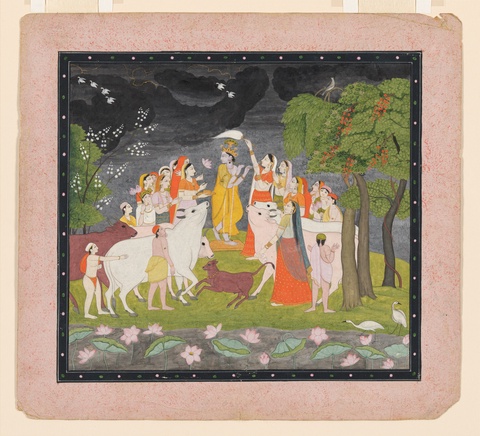

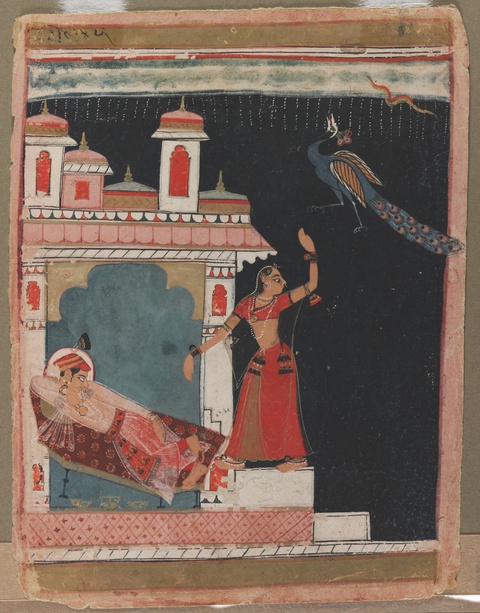

Tiger Hunt of Raja Ram Singh II highlights shared conventions across Edo prints and Indian miniature court paintings. Similarly to the narrow dark stripe at the top of Edo prints such as Utamaro’s Net Fishing at Night on the Sumida River, Rājput courtly paintings often indicated night scenes with a symbolic pattern. While the sky was often conventionally dark in these paintings, a narrow band of dark clouds at the top often marked scenes as happening at night.8 This is apparent in works such as Tiger Hunt of Raja Ram Singh II or Krishna Fluting for the Gopis (unattributed, late 18th or 19th century). The nights Edo and Rājput artists depicted were neither defined by dark backdrops nor associated with negative, sinister connotations.

Nightless Cities

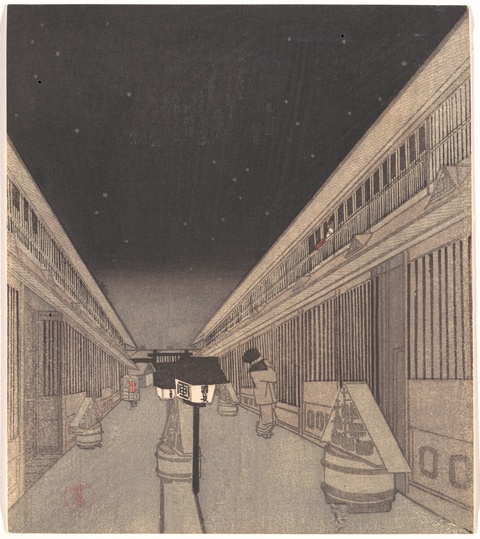

The Yoshiwara pleasure district is an archetype of the “nightless cities” described in an Edo poem, where “dawn was breaking as the sun set over the city.”9 Instead of a time of darkness, the night was marked by lavish illumination. In Main Street of the Yoshiwara on a Starlight Night by Utagawa Kunisada II, while the darkness of the sky is more prominent than is usual in Edo prints, the district itself is still steeped in a luminescence of its own. For any pleasure district, nighttime meant prime business hours for spirited entertainment.10

Paris, famously nicknamed the “city of light” at the beginning of the 19th century for its early adoption of gas lighting,11 was actually marked by a pronounced darkness.12 Edo prints featured luminous night scenes where light sources such as moons, torches, lanterns, and even stars, while central to establishing the scene as nighttime along with moods and feelings, were inconsequential to the quality of light in the print. Impressionist painters of the same period, on the other hand, portrayed a Paris submerged in darkness save for flickering street lamps.

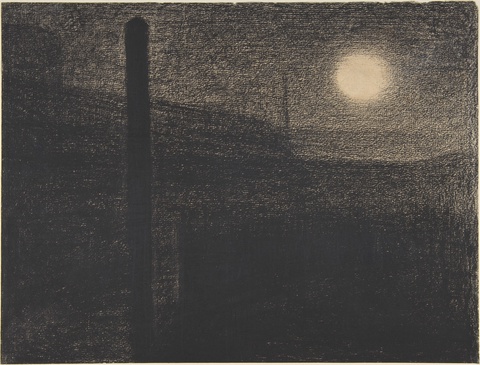

From the 17th century onwards, darkness overtook Western paintings, recounts Polish art historian Maria Rzepinska.13 Transformations in astronomical science, theology, and color theory led to a popularization of the genre of the nocturne, or night scene.14 Imbued with new meanings, obscurity becomes a metaphor not just for evil or sin, but a primordial chaos, both destructive and generative, and—most importantly—a medium necessary to perceive light at all.15 Two artistic techniques stand out in this “discovery of darkness” or “discovery of night,”16 both in sharp contrast with ukiyo-e prints’ orientation towards sharply pressed outlines and mostly no backgrounds: sfumato, or softened transitions, and chiaroscuro, shaping dimensions and contours through the use of bold contrasts of light and shadows, dissolving into deep impenetrable black.17

19th-century representations of Paris portray the city at night as overtaken by an oppressive darkness, dramatized by fog or the polluted skies of the industrial revolution. George Seurat’s drawing Courbevoie: Factories by Moonlight (1882–1883) is a monochromatic gradient from the pitch black outline of a tower structure to lighter but still quite dark skies enveloping the full moon. Rather than light being the source of vision, it is the surrounding darkness that makes the moonlight visible.

Theodore Earl Butler, Place de Rome at Night, 1905. Source: Wikimedia, public domain. Impressionist painting of a public place at night.

While impressionist paintings depart from the condensed light of chiaroscuro techniques, instead capturing more fleeting impressions of light in motion, they nonetheless still depict the city at night as overwhelmed by obscurity. Camille Pissaro’s Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897) emphasizes the deep blue night sky onto which even the outline of buildings recede, only interrupted by the perspectives and lines of flight traced by rows of flickering street lamps and the illuminated storefronts of department stores. The night sky presents itself as a formless chaos in which the interplay of darkness and light allows shapes to emerge. Theodore Earl Butler’s Place de Rome at Night (1905) renders the night as a dim, blue-grey atmosphere where everything seems to dissolve, from silhouettes of passersby to the outlines of buildings, except for impressionistic touches of scattered light.

In contrast, Edo print artists portray luminous nights full of sharp details. Most frequently, while the title and a few context clues like lanterns or the moon convey the nocturnal quality of a scene, the haziness and obscurity associated with nighttime is either absent or hinted at with negative space. A Party of Merrymakers in a House in the Yoshiwara on a Moonlight Night (1789) by Kitagawa Utamaro is a prime example. Even the moon referenced in the title is barely visible in the sky, only slightly paler than the mulberry paper. Utamaro portrays tangible, material obstacles in dark colors, such as the residential gate or the foliage which serves as a privacy screen, but the sky itself is represented by blank space.

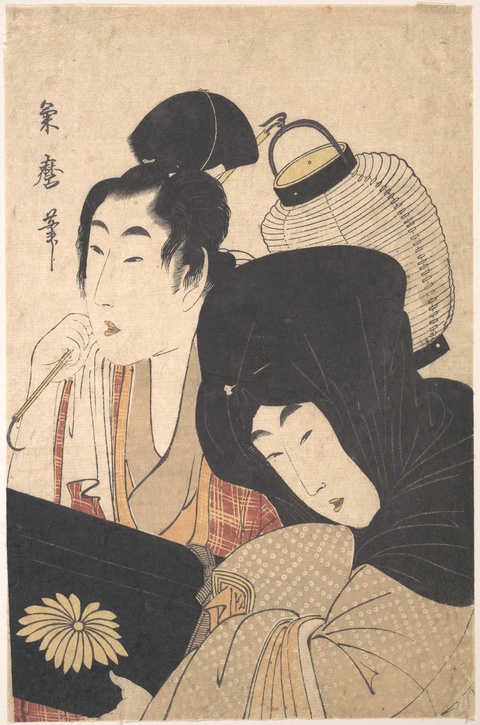

Similarly, the lantern in Kikumaro’s Young Woman at Night accompanied by a Servant Carrying a Lantern and a Shamisen Box (1789) does not function as a source of light for the print itself. The exterior structure of the paper lantern sheds no reflected light on the protagonists’ jet black hair or head covering. The clothing of the woman and her servant show intricate details in pale colors, contrasting with the shamisen, also black. Unlike Parisian night depictions in which the palette is marked by monochrome gradients or affected by the warm or cool tones of the lights, the nocturnal quality of the Edo period scene does not affect the range of colors portrayed. Unlike the obscure, anguished nights of Western art, Edo artists express no such anxieties about nighttime sights, emphasizing instead the intricate details of the new types of sociality, activities, and spectacles that urban lights allowed.

Ecological Spectacles

Aside from the sociality of the pleasure districts, ukiyo-e prints also featured highly popular ecological spectacles afforded by the night, such as watching certain plants or trees blossom, or catching fireflies. Hunting fireflies evolved from an aristocratic amusement to a popular nocturnal form of leisure popularized in Edo Japan.18 A 1928 travel guide mentions an annual Battle of the Fireflies (Hotaru-Kassen) on a river between Uji and Fushimi:

“Thousands of persons come hither from Kyōto (tram-cars), Ōsaka, Kobe, and nearby cities to witness the brilliant struggle. . . . The uncounted millions of sparkling insects produce a scene of bewildering beauty as they wheel and circle . . . and the scores of illuminated boats on which there are dancing and singing, geisha, music, and jollity, add to the charm. When the fireflies have assembled in force myriads dart from either bank and meet and cling above the water. At moments they so swarm together as to form what appears to the eye like a luminous cloud, or like a great ball of sparks. . . . After the Hotaru-Kassen is done, the river is covered with the still sparkling bodies of the drifting insects.”19

Kitagawa Utamaro’s Catching Fireflies (1796–1797) features a group of women and children in colorful garments. A set of specialized accessories such as round fans with ornate designs to catch the fireflies and a cage, hint at the codified character of this summer outdoor activity.

In contrast with the conventional narrow dark stripe at the top of Utamaro’s print, Suzuki Harunobu’s version of Catching Fireflies (1767) depicts the night sky more explicitly, as a flat black area contrasted with clear swampy grounds and waters. Strikingly, Utamaro’s fireflies did not glow in the night sky. Harunobu’s fireflies do light up against the night sky, but not against the pale ground. Eishōsai Chōki’s Woman and Child Catching Fireflies (ca. 1793) is a rare attempt to represent a light halo around the insect’s bodies, contrasted against a dark night backdrop. Still, the vibrant colors of the plants, the grounds, or the garments give the scene an otherworldly luminosity. In _Woman Admiring Plum Blossoms at Night _(1766), Harunobu gives even more prominence to the night sky, suddenly occupying two thirds of the print. While the woman holds a lantern, the night scene still has brightness, manifested in the detail of the flowering tree branches, for instance, that owes little to the paper lantern.

Complex Emotions in Dark Environments

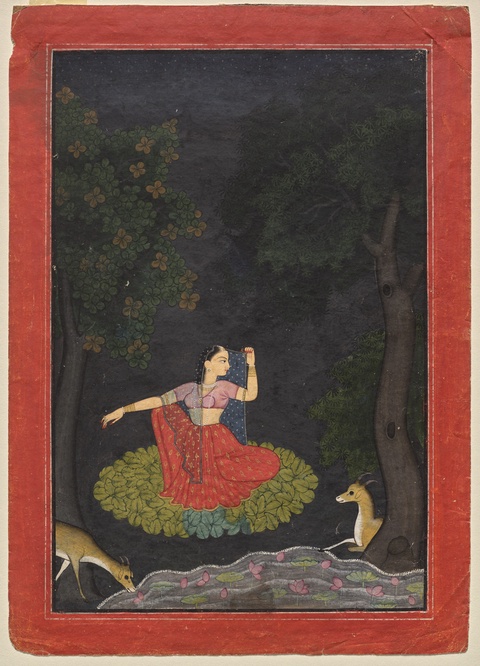

In the less urbanized context of Rajasthan, the nocturnal environment emerges not as a spectacle but as an allegory for complex emotions. In nightly scenes, animals often appear caught, mesmerized, or enchanted by light sources or musical instruments controlled by humans or divine beings. The prey in both examples above appears caught in an inescapable net of light. The noble archer, in a shooting stance behind the female tracker holding a lamp, makes plain the thin edge between seeing and killing. While the deep blue or black of the background seems to place these paintings closer to the Western Paris paintings, Rajasthani painters don’t evidence any desire to use modulating techniques such as chiaroscuro or sfumato.

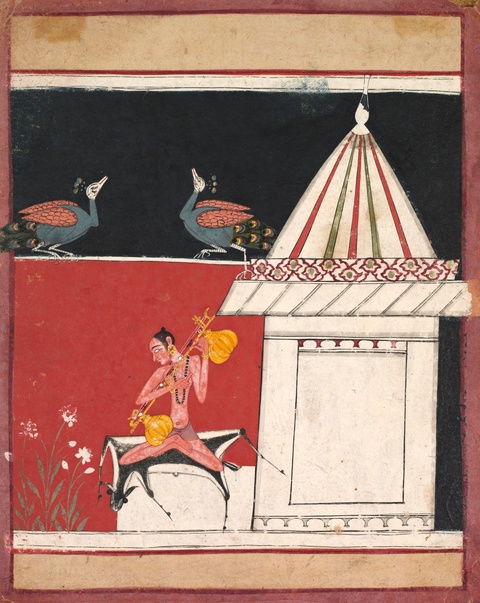

Deers in headlights are but one genre of spellbound wildlife in Rājasthānī paintings. In ragamala paintings, Kedara Ragini, the name of a female ascetic but also of the evening melody she personifies,20 captivates birds while playing the veena instrument, to the point that the birds seem to sing along with her sorrowful tune.21

We can see a similar emphasis on enchantment in other Rājput paintings from other parts of South Asia. Krishna, also conventionally represented at night because of one of his names, “Dark-cloud,”22 often appears playing the flute and enchanting gopis and cows alike, as in the Pahāri painting Sri Krsna with the flute (1790–1800, unattributed). In the Malwa court’s Krishna's Insomnia (1634, unattributed), docile deers and a bird accompany him in a sleepless night. Animals, lovers, nocturnal environments, but also the weather, such as the rain, all stand as allegories for a complex emotional landscape, expressing feelings of tenacity, tenderness, rapture, or devotion, among others.

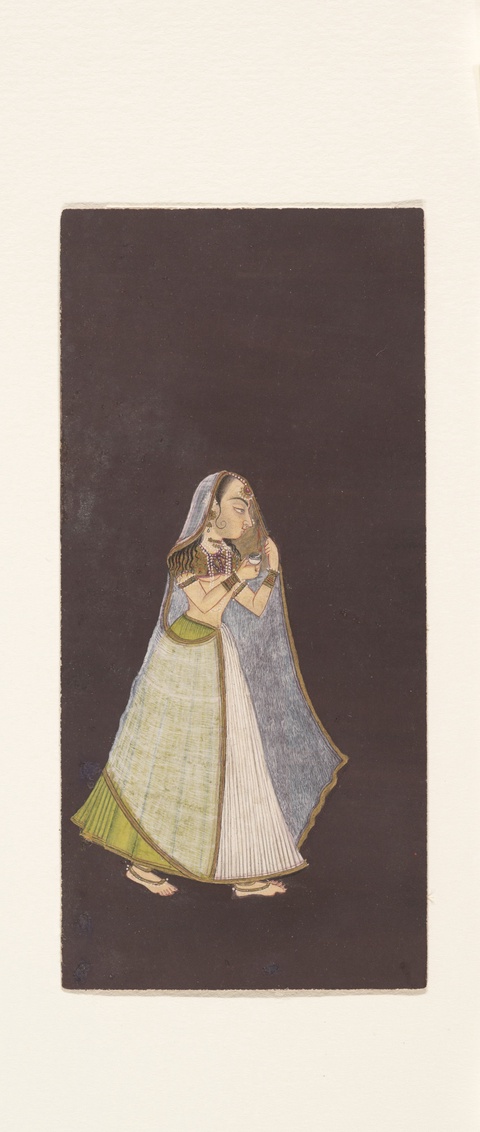

Women at night figure prominently in Edo prints, but even more strikingly in Rājput paintings. These paintings trouble gendered assumptions about who can inhabit the role of the adventurer, in particular the nightwalker. In A Lady Walking at Night Holding an Oil Lamp (ca. 1725), as with the lanterns of Edo paintings, the light of the oil lamp barely figures, drowned in the deep black backdrop. Pahāri paintings portray heroines confidently braving the night to wait for lovers in dark forests, as in A Heroine Waiting for Her Paramour (ca. 1750, unattributed), or The Heroine Who Waits Anxiously for Her Absent Lover (ca. 100 CE, unattributed).

In this Malwa court painting, Madhu Madhavi Ragini (unattributed, ca. 1630–40), a pair of lovers is separated by the threshold between the domestic interior and the outside, nocturnal environment. Strikingly, the heroine stands outdoors, sheltering herself from the incoming monsoon rain and lightning with her raised hand, while her reclining beloved observes her from a bench inside the house. The majestic peacock, on the other hand, seems to embrace the new season announced by the rain—and with it, all transitions.

Fragmented Night Skies

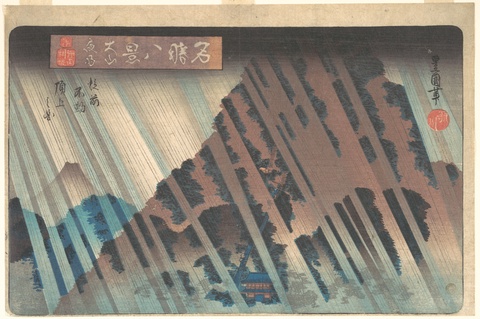

Torrential night rains are a frequent motif of Edo ukiyo-e. For this reason, famed print artist Hiroshige was nicknamed “the poet of rain.”23 In the Night Rain series, clear night skies are fractured by dark, geometric curtains of rain; perhaps the heavy summer downpours of the rainy season, known as tsuyu, or the torrential rainfalls of typhoon season, known as taifu. Utagawa Toyokuni II’s Night Rain at Oyama (ca. 1830) features Mount Oyama west of Edo, known as a pilgrimage site to pray for rain (a handful of brave pilgrims can be seen ascending steep staircases leading to a temple), and Mount Fuji in the distance. Despite the presence of these monumental landscape elements, it is the rain that is the centerpiece of the work.

Different atmospheric qualities and intensities of rain are infused with a sense of dynamism and directionality, as either thin parallel gray lines pour straight down, disappearing into the signature deep Prussian blue of Hiroshige’s waters24 in _Night Rain at Karasaki _(c. 1845), or cascade diagonally along the mountain flanks in slanted bands in Utagawa Toyokuni II’s Night Rain at Oyama (ca. 1830) or Torii Kiyomasu II’s _Night Rain at Karasaki _(18th century). In the latter, people caught by the rain hurry in all directions, using conical umbrella-hats known as kasa to protect themselves. In Toyokuni’s work, the rain pours down from the conventional narrow strip of dark night sky and pierces through the mountains, a visual effect achieved by the absence of outline, the use of negative space, as well as the earthy shade the rain takes as it falls onto the landscape, interrupting its otherwise dark forested surface.

Convergences

By the first half of the 20th century, these unique pictorial conventions of the night in Japanese woodblock prints start to falter. In post-Edo works such as Hasui Kawase’s Night Rain at Kawarago (1947) or Sekino Jun’ichiro’s Night in Kyoto (1980), depictions increasingly align with some Western conventions, such as dark backgrounds with shadows and highlights, as the artists suddenly bring “the evening sky to the forefront.”25 Hasui Kawase, trained in classical Japanese woodprint conventions and Western style painting, merges both styles.26 Thick black outlines still orient the gaze, but they share space with a mournful gray atmosphere which permeates every surface, from the façades of buildings to the ground. The rain is a collection of thin white dotted lines. It no longer vigorously ruptures the image, united in a single, ruler-bound direction, yet it still introduces, if more subtly, an unnaturally geometric discontinuity. The slightly warmer tones emitted by illuminated windows are fast absorbed into the night’s cooler shades: these are eerily self-contained light sources, which fail to project outwards onto neighboring surfaces. Similarly, Indian painting traditions change under multiple influences. The succeeding Mughal court painters, in particular, imbue night scenes with a naturalism associated, at that time, with European paintings.27

Citations

On the cultural politics of satellite representations see: Cosgrove, Denis. “Contested Global Visions: One-World, Whole-Earth, and the Apollo Space Photographs.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 84, no. 2, June 1994, pp. 270–294, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1994.tb01738.x. Accessed 23 June 2025; DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” Public Culture, vol. 26, no. 2, 2014, pp. 257–280, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2392057. Accessed 23 June 2025; Lekan, Thomas M. “Fractal Eaarth: Visualizing the Global Environment in the Anthropocene.” Environmental Humanities, vol. 5, no. 1, 2014, pp. 171–201, https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615469. Accessed 23 June 2025.

Derrida states, the “metaphor of darkness and light (of self-revelation and self-concealment) [is] “the founding metaphor of Western philosophy as metaphysics. The founding metaphor not only because it is photological one—and in this respect the entire history of our philosophy is a photology, the name given to a history of, or treatise on, light—but because it is a metaphor.” Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. University of Chicago Press, 1978, p. 78. In his 1837 Philosophy of History, G. W. F. Hegel famously used the transition from day to night as a racist, colonial metaphor for stages of historical development. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Lectures on the Philosophy of History. Translated by John Sibree. Dover Publications, 1837, p. 109.

Rzepinska, Maria, and Krystyna Malcharek. “Tenebrism in Baroque Painting and Its Ideological Background.” Artibus et Historiae, vol. 7, no. 13, 1986, pp. 91–112, https://doi.org/10.2307/1483250. Accessed 23 June 2025.

Nishiyama, Kazuo. Edo culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600–1868. University of Hawaii press, 1997.

Nishiyama, p. 39.

Nishiyama, p. 44.

Every raja had dedicated court painters, musicians, dancers, poets etc. Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. Rājput Painting. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, p. 11.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. Rājput Painting. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, p. 12-13.

Quoted in Koch, Angelika. "Nightless Cities: Timing the Pleasure Quarters in Early Modern Japan." KronoScope, vol. 17, no. 1, 2017, pp. 61–93. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685241-12341370. Accessed 23 June 2025.

In addition to Koch, op. cit., p. 62, see De Becker, Joseph Ernest. The Nightless City: The History of the Yoshiwara Yukwaku. Japan: Max Nössler & Co., 1899, p. 255.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. Disenchanted night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century. Univ of California Press, 1995, pp. 20-32.

In his memoirs, Baron Haussmann, selected by Napoleon III to carry out an ambitious redesign of the city, notes that the capital city before his arrival in 1853, is lit by more than 12,000 inefficient gas lamps and 1600 even less efficient hanging oil lamps, and only for six months of the year. Haussmann, Georges-Eugène. Mémoires du baron Haussmann. Vol. 1. Victor-Havard éditeur, 1890, pp. 152-54.

Rzepińska and Malcharek, pp. 91–112.

Rzepińska and Malcharek. See also Valance, Hélène. Nocturne: Night in American Art, 1890-1917. Yale University Press, 2018.

Rzepińska and Malcharek, p. 105.

Rzepińska and Malcharek, p. 91.

Capon, Edmund and John T. Spike. Darkness and Light, Caravaggio and his world. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2003; Lindsey, Renee J., The Truth of Night in the Italian Baroque, Thesis in Art and Visual Studies, University of Kentucky, 2015, pp. 8-9.

Prischmann-Voldseth, Deirdre A. “Fireflies in Art: Emphasis on Japanese Woodblock Prints from the Edo, Meiji, and Taishō Periods.” Insects, vol. 13, no. 9, 27 Aug. 2022, p. 775, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13090775. Accessed 23 June 2025.

Terry, T.P. Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire: Including Korea and Formosa, with Chapters on Manchuria, the Trans-Siberian Railway, and the Chief Ocean Routes to Japan: A Handbook for Travellers; Houghton Mifflin Company: New York, NY, USA, 1928, p. 552.

Pal, Pratapaditya. The Classical Tradition in Rājput Painting. New York: The Gallery Association of New York State, 1978, p. 102.

Each Ragini is associated with a specific time (i.e. dawn, night), a season, and particular emotions. Kedara Ragini is associated with nighttime, sorrow and sadness. See Markel, Stephen. “Unpublished Ragmala in the Michigan Museum of Art,” Roopankan: Recent Studies in Indian Pictorial Heritage, Padmashri Ram Gopal Vijaivargiya Felicitation Volume. Edited by V. S. Srivastava and M. L. Gupta. Jaipur: Printwell, 1995, pp. 70-83. Accessed 23 June 2025.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. Rājput Painting. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, p. 44.

Tola, M. Maya. “Rain in Japanese Art.” Daily Art Magazine, 2025, http://www.dailyartmagazine.com/the-rain-in-japanese-art/. Accessed 23 June 2025.

McCouat, Philip. "Prussian blue and its partner in crime." Journal of Art in Society, 2014, http://www.artinsociety.com/prussian-blue-and-its-partner-in-crime.html. Accessed 23 June 2025.

Dennis, Leeza. "Shin-Hanga and the Night Sky: Analyzing Celestial Bodies in the Works of Hasui Kawase." 2016, p. 5, Texas State University, Honors Thesis, https://digital.library.txst.edu/items/c33ba8f5-0194-4fc6-acce-d88ae3a95937, Accessed 23 June 2025.

Ronin Gallery, “Hasui (1883 - 1957),” http://www.roningallery.com/artists/Hasui. Accessed 23 June 2025.

See Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. Rājput Painting. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, p. 30; and Aitken, M. E. The Intelligence of Tradition in Rajput Court Painting. Yale University Press, 2010, pp. 79-82.