Monasteries and Brothels: Architectures of Control

By Noa Rui-Piin Weiss•July 2022•11 Minute Read

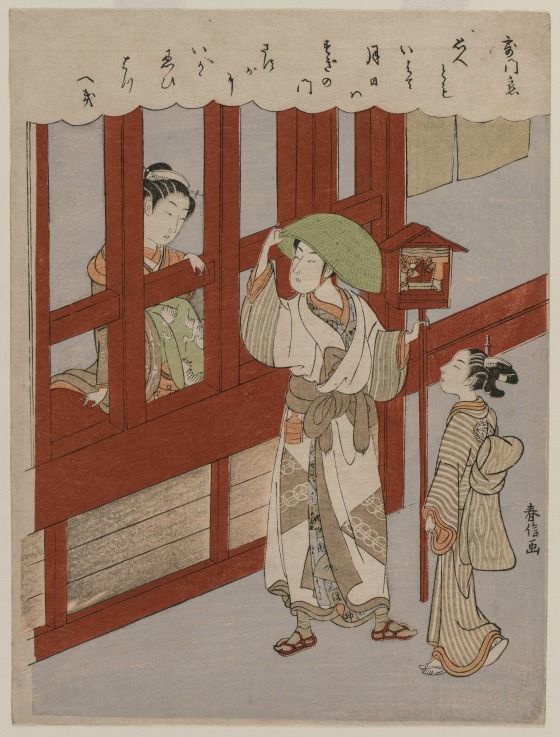

Suzuki Harunobu, Love at the Brothel Gate, late 1760s. Cleveland Museum of Art. Suzuki Harunobu's prints depict the lives of courtesans living in legalized red light districts.

In some ways, brothels and monasteries are opposites: the first is designed for sex, the second for abstinence. However, their common focus on sexual behavior leads to similar architecture that enacts the overlapping power dynamics surrounding gender and sexual activity.

Introduction

Monasteries and brothels are buildings that attempt to combine contradictory ideas: accessible to the outside world, but committed to privacy; segregated into individual rooms, but emphasizing communal living. And both prioritize sex as a category, clearly delineating and separating people along the binaries of male and female. Across cultures, religions, and time periods, monastic and brothel architecture are shaped by patriarchal control over bodies.

Isolation and Access

Visitors to brothels and monasteries find a similar first encounter: the gate. The feature is a portal between worlds, but also a marker of symbolic separation. The presence of a strong barrier guarding pleasure palaces and convents alike leads to questions: who do the walls confine, and who can pass through the opening? Who is taken through by force, and who enters freely?

An Escape, but for Whom?

Enclosure is a distinctive feature of public brothels throughout history. Establishments like the one depicted in this print by Suzuki Harunobu were often located in walled neighborhoods. Although they were segregated from society, brothels were a driving force in the ukiyo, or “floating world” (浮世) cultural movement, developed in the Edo period (1600-1867). The Edo government established red light districts like Yoshiwara, Shimabara, and Shinmachi in major cities.1 2 3 Sex work was legal, but its legality was contingent on limiting the movement of the workers to designated neighborhoods.

The rise of legal, urban sex work led artists to focus on sensuality and urban activities. Pleasure districts served as an escape for men living in a straitlaced society, offering access to new experiences as well as different cultural strata.

However, the sex workers who populated the “floating world” did not reap the benefits of ukiyo’s characteristic escapism. In fact, they were bound: their livelihood confined them to one neighborhood or even one building. Most 17th-century sex workers were indentured to their brothel, working in an economic system that often drove them further into debt than when they started.4

Love at the Brothel Gate, a woodblock print from the era, features a poem that reads: “Although I yearn, / I do not speak as days and months, / pass by behind my cedar gate. / How can I endure keeping this secret within?”5 The freedom that the clientele experienced depended in part on the restrictions placed on sex workers. The inscription on this print fetishizes this dynamic. The courtesan’s confinement heightens the stakes of her yearning for the young man outside the gate.

Same Rules, Different Setting

Freedom of movement in both brothel and monastery contexts is often tied to biological sex. Prostitutes and nuns are cloistered, monks and johns are encouraged to come and go.

The gate depicted in this etching by Charles Meryon belongs to a French Capuchin monastery that was founded in 1658 near the Acropolis in Athens. This period of the Capuchin order was one of increased agency under the Pope. The monks established property, heard the confessions of nonbelievers, and launched widespread missions.6 This French monastery in a Greek city is just one piece in a worldwide network developed by the well-traveled Capuchins.

Unlike claustrophobic portrayals of brothel gates, this depiction of a monastery gate features two figures on the open threshold with light pouring out from behind them. The entrance is permeable, and the decision to stay or leave is theirs. Compositionally, the etching reflects the realities of Capuchin monastic life. The process of committing to the Capuchin order centers choice: at each step, a monk takes months or years to decide how much of their freedom to give up.7 While the monastery gate still represents confinement and sacrifice, Meryon’s etching reveals that agency is the key difference between this gate and that of a brothel.

Compare the Meryon to an 1811 print titled Pastime in Portugal or a Visit to the Nunnerys by Thomas Rowlandson. Although it also illustrates the threshold of Christian monastic life, this drawing more closely resembles the 18th century Harunobu print of a Japanese sex worker. Like the woman in the Edo piece, Rowlandson’s nuns conduct business with the visiting men through the crossed bars of a gate. The grille is an essential feature of any cloistered convent—it maintains the bounds of the monastery even during the nuns’ brief, sanctioned interactions with outsiders.8 In both illustrations, the women are positioned behind a barrier while the men approach them as free agents. While there is a history of women in the church serving as missionaries, the fact remains that being cloistered is more common among Christian women than men. These images reflect that history.9

Looking Out or Looking In

Images of buildings are not neutral. Even the angle an artist chooses can tell you something about how the architecture is used and perceived.

This image depicts the Nectarine Brothel, also known as No. 9 or Jimpuro.10 It first opened in 1872 at Takashima-cho, a major train station in Yokohama.11 Ten years later, The Nectarine relocated to the red light district of Kanagawa’s Nankin-machi (or Chinatown). Both sites were hubs of the thriving port town and associated tourist industry.

The photograph, captured approximately one hundred years after Suzuki created Love at the Brothel Gate, depicts a similar setup. The resident workers are framed in windows on the second floor of the building, visible but confined. Below, rickshaws line the entrance, ready to facilitate the coming and going visitors. Composed from street level, the photo shows how the architecture highlights the imprisonment of its workers for the benefit of traveling customers. The first floor entrance is underneath the veranda, with slatted windows and drawn shades across the facade. Pressed up against the railing, these women can only be seen when they are confined.

In contrast, consider View of Amalfi from the Capuchin Monastery, painted in the early 1800s. The view faces outwards, from the grotto near the monastery toward the coastal fishing village. Like the Nectarine, this site drew travelers from the nearby port town. Both brothels and monasteries can be tourist destinations, but sex workers are kept for the amusement of travellers, while captive monks are not part of a monastery’s draw. In this painting, the gate to the grotto has swung open. The barrier is thin and permeable, with glimpses of the ocean between the wide-set poles. The monastery is not closed off, but joins a visual continuity along the coastline and the buildings of Amalfi nearby.

Cells and Surveillance

The architectural similarities between brothels and monasteries continue indoors. Cells are a common, even essential, element in their designs. Individual rooms offer a semblance of privacy within a communal mode of living. Yet the aims and results of this architectural arrangement have different impacts between the two types of structures.

Brothels and Cells

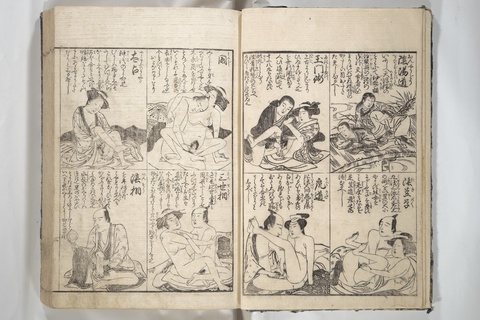

In brothels, cells provide privacy for sexual activity while maintaining the ability to surveil the movements of workers within the building. The rooms themselves are closed off, but the hallways that connect them ensure that no occupant can leave unobserved. The Compendium Guide to the Brothels of Osaka organizes its information in cells, each sex act happening in a separate box.12 The grid format resembles a series of individual, enclosed rooms, allowing the reader to voyeuristically peruse a variety of options. In fin-de-siècle Paris, luxury brothels advertised rooms that were self-contained fantasy worlds, from torture chambers to Rococo salons.13 Similarly, the rooms on the second floor of former Osaka brothel Taiyoshi Hyakuban have their own individual eaves, an architectural gesture that turns each room into its own building.14 Ledoux’s 18th-century proposal for the Oikema House of Pleasure in Paris was also structured around a phallic arrangement of galleries, hallways, and chambers.15

Across geography and time, brothels have used halls of cells to control their occupants. As Paul B. Preciado points out in his analysis of Oikema, the layout of the building represented the state’s ability to control women’s bodies: keeping sex workers enclosed and monitored, allegedly to stop the spread of syphilis.16 In this light, the similarities between these rows of single rooms and the cells of a prison are plain.

Monasteries and Cells

Cells are also a hallmark of monasteries, but unlike brothels, they are meant for spare, solitary living. Ancient buildings like the basement of the Coptic Monastery of Saint Anthony and the Vihara Halls in the Ajanta Caves were both identified as monasteries by the presence of cells.17 18 They are also part of the outward aesthetic of monasteries: Rila Monastery and the Monastery of Mega Spileon, pictured above, have exterior windows, displaying their cell organization on their walls.19 20

Surveillance and Sex

Buildings built for monastic life and sex work both have relationships to surveillance and sex, but with different gendered implications. Both represent control over reproduction and unevenly place the burden of hygiene and health on women.21 Brothels restrict the movement of their workers to keep them from getting pregnant or catching sexually transmitted infections off the clock without acknowledging that those same risks are present on the job. The male clients who facilitate these problems are free to come and go as they please, while the sex workers must stay and deal with the consequences.

Monasteries also restrict the movement of their inhabitants, but gender roles change how the power dynamics play out. Male religious orders are associated with deprivation or mortification of the body, but these consequences are voluntary. In short, when men withdraw from society, it is to commit themselves further to their own intellectual and existential pursuits.22 When women want to, or have to, leave everyday society, it often means submitting their bodies to patriarchal control.

Buildings for Sex, Buildings for Control

The final common factor between these archetypal buildings is their emphasis on sex. When people build buildings to control sexual behavior, they create institutions that solidify their conceptions of the human body. Monasteries are supposed to support celibacy, and are therefore “single-sex”—built under the assumptions that people are simply male or female, with only heterosexual urges. Brothels, meant to supply sexual activity, are usually designed around similar assumptions. Studying these buildings together reveals how systems of power make themselves concrete through architecture, and how institutions organized around sex aim to categorize and bind the human body.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator based in New York City. He is a regular contributor to Culturebot and The Brooklyn Rail. Noa's most recent performance collaborations include works by Hope Mohr/Maxe Crandall, Emily Coates, Mia Martelli, and Adrienne Truscott. He has presented choreography in collaboration with his BFFL Miranda Brown at Pageant, Fertile Ground, WAXworks, Current Showcase (Take.5), The Tank, SERIOUS PERFORMANCE!!!!, and the Movement Lab at Barnard College. Noa is currently the Programming Manager at The Joyce Theater. His writing for Curationist focuses on the histories of dance, sexuality, and sex difference in artwork. Recently, Noa has discovered a passion for mash-ups, and would recommend "Nine Inch Nails - Closer But It's Funkytown By Lipps Inc." by William Maranci.

Citations

“Yoshiwara.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Yoshiwara&oldid=1072727574. Accessed 1 July 2022.

“Shimabara, Kyoto.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shimabara,_Kyoto&oldid=1083426887. Accessed 1 July 2022.

“Shinmachi.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shinmachi&oldid=860821681. Accessed 1 July 2022.

“Yoshiwara.”

“Love at the Brothel Gate.” Cleveland Museum of Art, www.clevelandart.org/art/1921.349. Accessed 1 July 2022.

Hess, Lawrence. "Capuchin Friars Minor." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 3, Robert Appleton Company, 1908, www.newadvent.org/cathen/03320b.htm. Accessed 8 July 2022.

“Capuchin Friars, Morgon, France: Traditional Religious Orders.” The Angelus Online, September 2005, www.angelusonline.org/index.php?section=articles&subsection=showarticle&articleid=2465. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Shuman, Nancy. “The Bars of Our Grille.” The Cloistered Heart, 2 June 2014, www.thecloisteredheart.org/2014/06/the-bars-of-our-grille.html. Accessed 18 July 2022.

“Why ‘nun’ of the Missionaries of Charity are technically nuns at all.” The Pillar, 6 January 2022, www.pillarcatholic.com/p/why-nun-of-the-missionaries-of-charity. Accessed 8 July 2022.

noel43. “The ‘Nectarine’ Brothel in Kanagawa, Yokohama.” Nagasaki University Database of Old Photographs in Bakumatsu-Meiji Period. Flickr, 17 October 2014, www.flickr.com/photos/36560798@N02/48402186476/. Accessed 8 July 2022.

“The Nectarine Brothel in Yokohama Was a Famous House of Prostitution Also Known as No 9 or Jimpuro Until.” IMAGO, 20 January 20 2022, www.imago-images.com/st/0148300205. Accessed 8 July 2022.

“Erotica; Compendium Guide to the Brothels of Osaka.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78697. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Greene, Gina. “Reflections of Desire: Masculinity and Fantasy in the Fin-de-Siècle Luxury Brothel.” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 7, no. 1, spring 2008, www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring08/108-reflections-of-desire-masculinity-and-fantasy-in-the-fin-de-siecle-luxury-brothel. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Hanano, Yuki. “Former Brothel in Osaka Set to Be Restored Thanks to Crowdfunding.” The Asahi Shimbun, 16 August 2021, www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/photo/40330584. Accessed 8 July 2022.

“Oikema House of Pleasure by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.” Archeyes, 20 March 2020, archeyes.com/oikema-house-pleasure-claude-nicolas-ledoux/. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Preciado, Paul Beatriz. "The Architecture of Sex: Three Case Studies Beyond the Panopticon." Benno Premsela Lezing 2017, 1 October 2018, bennopremselalezing2017.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/lecture-text. Accessed 7 July 2022.

Litecky, Tessa and Elisabeth Koch. “The Ancient Monastic Cells of Saint Anthony Monastery.” American Research Center in Egypt, n.d. Google Arts and Culture, artsandculture.google.com/story/the-ancient-monastic-cells-of-saint-anthony-monastery/6AUBOwdDy1oTug. Accessed 8 July 2022.

“Ajanta Caves.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ajanta_Caves&oldid=1096947941. Accessed 7 July 2022.

“Rila Monastery.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Rila_Monastery&oldid=1096150956. Accessed 2 July 2022.

Toft, Peter. “Monastery of Mega Spileon, Greece.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/335820. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Preciado.

Carter, Jimmy, et al. “Deserts: Cells for certain individuals.” nonsite.org, issue 31, 10 April 2020, nonsite.org/deserts-cells-for-certain-individuals/. Accessed 2 July 2022.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator based in New York City. He is a regular contributor to Culturebot and The Brooklyn Rail. Noa's most recent performance collaborations include works by Hope Mohr/Maxe Crandall, Emily Coates, Mia Martelli, and Adrienne Truscott. He has presented choreography in collaboration with his BFFL Miranda Brown at Pageant, Fertile Ground, WAXworks, Current Showcase (Take.5), The Tank, SERIOUS PERFORMANCE!!!!, and the Movement Lab at Barnard College. Noa is currently the Programming Manager at The Joyce Theater. His writing for Curationist focuses on the histories of dance, sexuality, and sex difference in artwork. Recently, Noa has discovered a passion for mash-ups, and would recommend "Nine Inch Nails - Closer But It's Funkytown By Lipps Inc." by William Maranci.