The Making of American Dance History

By Noa Rui-Piin Weiss•July 2022•9 Minute Read

George Catlin, Dance to the Berdash, 1835-1837. Smithsonian American Art Museum. The Fox tribe embraces and celebrates Two-Spirit people, or i-coo-coo-a, as sacred figures.

The early 20th century marked a time of changing attitudes and innovations in American dance. But who gets remembered and credited, and even who gets to dance, is influenced by prevailing attitudes towards race, capital, and nationalism.

Introduction

Historical records of dance can often feel random. Who rises to fame, who goes down in history, and who gets the credit all seem to hang on chance or fate. But that’s not the whole story. To make sense of how dance history gets written, we have to look at the broader picture. Factors from documentation technology to national politics can all play a role in what dance makes its way into the archive and what is excluded. Taking three case studies from the 19th and early 20th centuries in America—social dance, modern dance, and Native American dance—this essay unwinds the twisting narratives leading to the current cornerstones of dance history.

Social Dance and Authorship

Social dances focus on participation over performance. In this sphere, innovation arises from community. So how do individual social dance celebrities come to exist?

Meet the Castles

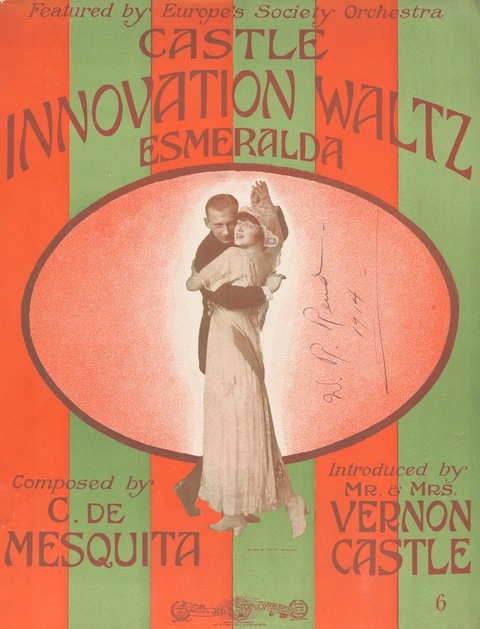

The Smithsonian credits Irene Foote Castle and Vernon Blythe Castle for changing moral attitudes in the early 20th century. They made social dance more acceptable through their skill and respectability.1 The museum’s collection contains a poster for the Castle Innovation Waltz, a title that paints the couple as responsible for a new contribution to the form. But authorship in social dance is notoriously slippery. Social dances morph as they move from body to body. Dancers take cues from accompanying musicians, their partners, and the surrounding community of dancers. Scholar and bearer of dance traditions LaTasha Barnes notes that every person who encounters and teaches a dance leaves a mark on it.2 The Castles capitalized on one aspect of this truth by attaching their names to their dances without crediting others.

Setting Steps

Irene and Vernon Castle saw society’s distaste for social dance as an opportunity. They worked on codifying movements, claiming particular repeatable steps as their own, and used these steps to build their own names. With the help of a number of wealthy patronesses, they opened Castle House, a dancing school in New York City.3 They wrote a book titled Modern Dancing, which contains instructions for the dances they codified, as well as an argument for destigmatizing social dance.4

Respectability and Race

In the introduction to Modern Dancing, literary agent Elisabeth Marbury celebrates the Castle Tango for its lack of “hideous gyrations” and “salaciousness.”5 At Castle House, “the much-misunderstood Tango becomes an evolution of the eighteenth-century Minuet.”4

The tango originates from Rio de la Plata, an area along the border between Argentina and Uruguay.6 As a partner dance developed in the global south, its presence in early 20th-century North America carried racial baggage. White American society has a history of considering non-white dances vulgar or sexual. Indeed, Marbury’s remarks on the tango are racially coded. She claims that the Castles have created a cleaner and more decent tango by turning it into something that could have European origins, like the minuet. This is what the Smithsonian means by changing moral attitudes: the Castles distanced social dances from their original, non-white cultures.

The Castles, a notably white couple, were invited into Black spaces by musicians. Europe’s Society Orchestra, the band featured in the Innovation Waltz poster, was an all-Black ragtime band who wrote music for the couple’s set dances.7 Irene and Vernon Castle emerged from these interactions with a place in history and credit for their contributions to the dances they embraced. When individual people get credit for innovations in American social dance, their presence should be a reminder of all the unnamed artists, especially Black innovators and people of color, whose contributions are not represented in archives or historical texts.

Copyright and Image

In contrast to the communal nature of social dance, high art gains much of its value from the idea of individual genius.

Loie Fuller: Dance Inventor

This was a concept that Loie Fuller understood well. Fuller was an American dancer and actress who moved to France in the late 1800s, hoping to gain serious recognition for her work.8 She was a modern dancer, performing in theaters for seated audiences. Fuller is famously remembered for inventing the Serpentine Dance, also known as the Butterfly Dance.9 It exists in a variety of forms, but usually involves a single dancer wearing a large swath of fabric and using sticks to extend the reach of her arms, swirling the garment around to create a mesmerizing, larger-than-life motion. To complete the effect, colorful lights lit up the sweeping costume from below.

Pursuing Copyright

Fuller was immediately swamped by a host of imitators. In response, she expanded the technical aspects of her performance. She also applied for patents on her lighting techniques and on the dance itself. She obtained a patent for her costume and technical innovations, but the U.S. Copyright Office refused her application to protect her movements on the grounds that the dance was non-narrative.10 Her innovative, abstract approach was too far ahead of the law’s concept of dance.11

Ownership vs. Image

This portrait of Loie Fuller is one of relatively few images of the choreographer. Posters and drawings are more common—forms where other artists have more creative control. There is no archival footage of Fuller herself performing the Serpentine Dance.12 However, many videos of her imitators remain.13

Fuller pursued copyright because she assumed it would guarantee her control over her artistic legacy. Unfortunately, she overlooked a growing force in the world of artistic authorship: documentation. Fuller was leading a technical revolution in live performance, but she ignored the concurrent revolution of motion pictures. The mediums that Fuller preferred—staged portraits and patents—are more difficult to access, fall short of the experience of live movement, and ultimately make it harder to attach credit to her art.

Indigenous Dance, the Nation, and Extinction

While Loie Fuller was trying to protect her movement by attaching her name, naming Indigenous dance became a way to eradicate it. Just as Fuller’s case ultimately hinges on the American legal concept of artistic ownership, the state’s concept of self also determines who gets to dance.

Colonial Control through Dance

The early 20th century marked a turn in American colonial attempts to eradicate Indigenous culture and suppress its sovereignty. The new strategy was to assimilate Native Americans into white America, and therefore strip them of special rights and protections. Professor Jacqueline Shea Murphy’s book The People Have Never Stopped Dancing (2007) argues that part of the government’s campaign to eradicate Native traditions involved defining dance as a distinctive cultural practice.14 Dance encompassed Native American religious life, healing practices, and tribal history. If the government could define and outlaw Indigenous dances, they could erase Indigenous society at large.

Interpretation by White Artists

At the same time, white visual artists were invested in recording Indigenous cultural practices. This type of preservation served less to allow community members to continue to practice the form, and instead historicized and classified dances according to colonial standards. In a series of oil paintings made in the early to mid-19th century, George Catlin interprets and comments on various Native American movement traditions.15 His painting Dance to the Berdash portrays a ceremony honoring a berdache, a colonial term for a member of the community who does not conform to Western gender standards.16 In his notes, he describes expansive gender presentation as “degrading” and calls the dance “funny and amusing.” In documenting and labeling this ceremony, Catlin points out the distance between Indigenous culture and colonial society. The same type of interpretation set the stage for the American government to ban Indigenous dance in the late 1800s on the grounds of morality—establishing a difference between “barbaric” Native American practices and “rational” Christian beliefs.17

National Identity and Extinction

Framing Indigenous dances as “other” places them in opposition to the state—meaning the idea of the United States of America as a white nation that does not include Indigenous people. It’s a step toward genocide. In the case of Indigenous dances, codifying serves to suppress the dancers and their communities. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, naming and capturing a dance was part of a larger project to end its living practice: archiving it to death.

Who Gets Remembered?

Dance is an ephemeral form. Collecting and preserving traces of its presence takes intellectual commitment and resources. As with all types of history, dance history records information about the power structures at play. These three examples show that the historical record is not just a story of who danced or how, but of who was invested in capturing different forms of artistry, and why. The holes in the archive are reminders of those moving bodies who have gone uncredited.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator based in New York City. He is a regular contributor to Culturebot and The Brooklyn Rail. Noa's most recent performance collaborations include works by Hope Mohr/Maxe Crandall, Emily Coates, Mia Martelli, and Adrienne Truscott. He has presented choreography in collaboration with his BFFL Miranda Brown at Pageant, Fertile Ground, WAXworks, Current Showcase (Take.5), The Tank, SERIOUS PERFORMANCE!!!!, and the Movement Lab at Barnard College. Noa is currently the Programming Manager at The Joyce Theater. His writing for Curationist focuses on the histories of dance, sexuality, and sex difference in artwork. Recently, Noa has discovered a passion for mash-ups, and would recommend "Nine Inch Nails - Closer But It's Funkytown By Lipps Inc." by William Maranci.

Citations

“Irene Foote Castle.” Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/object/irene-foote-castle%3Anpg_NPG.94.10. Accessed 31 May 2022.

“May We Have This Dance?: Rough Translation.” NPR, https://www.npr.org/2021/12/22/1066965712/may-we-have-this-dance. Accessed 23 May 2022.

For a complete list of patronesses, see Vernon and and Irene Castle, Modern Dancing, 1914.

Castle, Vernon and Irene Castle. Modern Dancing. World Syndicate Company, 1914, https://books.google.com/books?id=XhBnlE5uN6cC.

“Elisabeth Marbury.” Wikipedia, 14 December 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elisabeth_Marbury&oldid=1060251106. Accessed 27 January 2023.

“Tango.” Wikipedia, 25 May 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tango&oldid=1089779153. Accessed 27 January 2023.

“Europe’s Society Orchestra." The Syncopated Times, https://syncopatedtimes.com/europes-society-orchestra/. Accessed 24 May 2022.

“Loie Fuller.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Loie-Fuller. Accessed 24 May 2022.

Garelick, Rhonda K. “Loie Fuller and the Serpentine.” The Public Domain Review, htps://publicdomainreview.org/essay/loie-fuller-and-the-serpentine/. Accessed 24 May 2022.

Fuller, Marie Louise. United States Patent US518347A, 17 April 1894, https://patents.google.com/patent/US518347/en?oq=518347. Accessed 24 May 2022.

Kraut, Anthea. Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance. Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 43. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/columbia/detail.action?docID=4082954.

Albright, Ann Cooper. Traces of Light: Absence and Presence in the Work of Loie Fuller. Wesleyan University Press, 2007.

See Debbi Richard, "Serpentine Dances," 2009, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oB6zF7Jb3kg. Accessed 27 January 2023.

Murphy, Jacquelin Shea. The People Have Never Stopped Dancing. University of Minnesota Press, 2007, pp. 34.

"George Catlin Biography," georgecatlin.org, https://www.georgecatlin.org/biography.html. Accessed 3 June 2022.

"Berdache," Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/berdache. Accessed 3 June 2022.

Murphy 40.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator based in New York City. He is a regular contributor to Culturebot and The Brooklyn Rail. Noa's most recent performance collaborations include works by Hope Mohr/Maxe Crandall, Emily Coates, Mia Martelli, and Adrienne Truscott. He has presented choreography in collaboration with his BFFL Miranda Brown at Pageant, Fertile Ground, WAXworks, Current Showcase (Take.5), The Tank, SERIOUS PERFORMANCE!!!!, and the Movement Lab at Barnard College. Noa is currently the Programming Manager at The Joyce Theater. His writing for Curationist focuses on the histories of dance, sexuality, and sex difference in artwork. Recently, Noa has discovered a passion for mash-ups, and would recommend "Nine Inch Nails - Closer But It's Funkytown By Lipps Inc." by William Maranci.