Porcelain to Peonies: Chinoiserie and the Fantasy of Nature

By J. Cabelle Ahn•September 2025•15 Minute Read

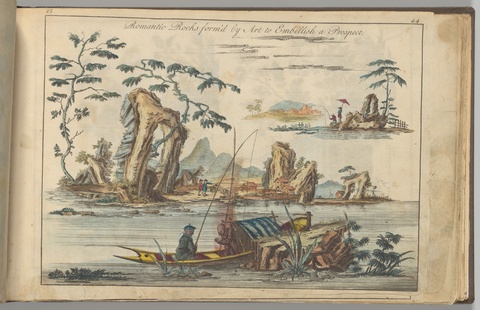

Jean Pillement, Ladies Amusement: Or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy, 1760, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain.

Chinoiserie once enchanted Europe with its visions of exotic gardens and whimsical figurines. Yet beneath that charm lay a history of colonial trade and cultural distortion—shaping how the West consumed and reimagined Asia for centuries.

Introduction

From gleaming screens to blooming embroidery, chinoiserie—a European decorative style that emerged in the 17th century—has long been seen as whimsical, romantic, and refined. Chinoiserie was a style defined by recurring motifs inspired by pan-Asian decorative motifs and often applied to architecture and decorative arts. But beneath its ornamental surface lies a deeper, more complicated history. Rooted in the Dutch East India Company (VOC) trade routes and fueled by Europe’s colonial appetite for Asian goods, chinoiserie reshaped people, places, and cultures. It fed into a pan-Eurasian fantasy that could be marketed, bought, and sold. Tracing how the style infiltrated Western art, design, and architecture reveals a throughline: chinoiserie’s charm was built on making nature unnatural—a legacy we still contend with today.

Dutch Routes, Chinese Roots

One of the foundational conduits in the popularization of chinoiserie was the VOC. Founded in 1602, the company became one of the world’s first multinational corporations, operating across a vast network of trading posts stretching from South Africa to Southeast Asia.1

A 17th-century painting of Canton, now Guangzhou, shows the bustling port where the VOC’s ships docked to trade tea, silk, and porcelain, as well as traffic enslaved people. The work was part of a series of paintings shown at the VOC headquarters in Amsterdam in the 17th and 18th centuries. The painting was exhibited alongside views of Cochin (now Kochi) on the Malabar coast and Judea (now Ayutthaya) in present-day Thailand—a display that sought to underscore the company’s global reach.2

Fragments from the wreck of the VOC ship Witte Leeuw offer an intimate glimpse into the types of cargo they ferried from port to port. The ship sank off St. Helena, an Island in the South Atlantic, in 1613 on its return from Asia. Among the wreckage was a porcelain cup, likely from Jingdezhen, fused over time to rusted iron in a haunting merger of Chinese craft and Dutch colonial ambitions.3

The VOC played a central role in bringing both natural specimens and crafted goods—from shells to textiles—into Europe through its trading posts. Among the most significant imports was Kraak porcelain, produced in Jingdezhen specifically for European buyers.4 The name “Kraak” is thought to derive from “carraca,” a type of Portuguese merchant ship, underscoring the entangled routes of maritime trade. These porcelain wares often bore floral motifs and Buddhist emblems that appealed to European tastes, almost always in blue on a white background (as in the examples shown above), and were among the first porcelains to be mass-imported to Europe. They quickly became fixtures in Dutch still-life painting, where they signified wealth and global reach. Export wares such as this demonstrate how Asian makers and communities found ways to profit within this trade, though rarely on equal terms.5

Interior View of the Kitchen in Amalienburg, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich, Germany, c. 1734-39. Wikimedia Commons, user: Massimop, CC BY-SA 3.0. In this photo of the Amalienburg kitchen at Nymphenburg Palace, blue-and-white tiles cover the walls, with a lower register of chinoiserie-inspired vignette tiles beneath larger floral panels; a square tiled hearth sits on hexagonal terracotta flooring.

In response to this influx of goods imported by the VOC, Delft potters produced earthenware mimicking prized blue-and-white East Asian porcelain. The fashion spread fast. In Bavaria, Electress Maria Amalia lined her kitchen in the Amalienburg hunting lodge with Delft-style tiles featuring chinoiserie imagery.6 Interiors such as these demonstrate that VOC imports were refashioned into sweeping ornaments where flora, fauna, and figures were transformed into cobalt-hued patterns that rendered the natural world distant and collectible.

Printing Fantasy

In 18th-century Europe, chinoiserie wasn’t limited to faux porcelain—it also thrived in print. Johan Nieuhof, who served as an ambassador of the VOC embassy to Beijing in 1655, published Embassy to China (1665), a travel account that included over one hundred engravings of sites, customs, and farming practices in China. Translated into Latin, French, and English, the travel album quickly became an influential visual source to inspire a new class of pattern books no longer rooted in historical and natural referents or first-hand accounts.7

Pierre-Joseph Buc'hoz, A precious and illuminated collection of the most beautiful and curious flowers grown in the gardens of China and Europe, 1776. Wikimedia Commons, user: Gzen92Bot, Public Domain.

One genre of pattern books derived from botanical studies. Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, a prolific French naturalist, published thousands of plant illustrations in the mid-1700s.8 But pages from his _Collection précieuse et enluminée des fleurs les plus belles et les plus curieuses qui se cultivent tant dans les jardins de la Chine que dans ceux de l'Europe _(1776) echo the visual language of imported “Chinese” art, blurring the boundary between scientific taxonomy and fanciful invention. Nouvelle suite de cahiers de fleurs idéales à l'usage des dessinateurs et des peintres dessinés (1790–99), designed by Pillement and etched by his wife, Anne Allen, pushes the distortion further, turning plants into imaginative spirals and otherworldly forms.9 As the title suggests, Pillement and Allen’s prints presented “ideal” flowers to be used as models for designers, draftsmen, and painters. Such images helped spread Europe’s fascination with the exotic, recasting the ecological diversity of Eastern nature as a repertoire of stylized motifs that bore little resemblance to their natural sources. In the process, they cemented the visual template for chinoiserie.

Distinctions among East Asian and Southeast Asian sources collapsed into one broad pan-Asian category during the 18th century. In Ladies’ Amusement; or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy (1758), the author and publisher Robert Sayer advised that, “With Indian and Chinese subjects greater Liberties may be taken, because Luxuriance of Fancy recommends their Productions more than Propriety, for in them is often seen a Butterfly supporting an Elephant, or Things equally absurd.”10 The publication contained more than 1,500 original images designed and engraved by Pillement of fanciful nature and dramatized architecture of disambiguated Asian inspirations, including floating pagodas, hybrid insects, and stock figures with exaggerated physiognomies, that could be easily transferred onto embroidery, home furnishings, furniture, and interior decorations. The title was a reference to japanning, a type of imitation lacquer practiced by wealthy British women as a genteel pasttime.11

François Boucher, premier painter to Louis XV, also played a key role in France by popularizing chinoiserie print suites.12 An avid collector himself of East Asian objects (as per his posthumous inventory), Boucher designed rococo scenes of “Chinese” doctors, botanists, and musicians that were disseminated as print suites that could be adapted into paintings, tapestries, and porcelain for elite consumers, with these goods becoming markers of cosmopolitanism.

A coffee pot made by the Royal Porcelain Factory in Berlin featuring a scene after Boucher makes artisanal networks of chinoiserie visible. French manufactories produced imitation, or soft-paste, porcelain until Meissen in Germany perfected true hard-paste porcelain in 1710.13 During this period of technical evolution, European artisans had looked directly to East Asian export wares—Chinese Dehua and Kraak and Japanese Kakiemon and Imari—for visual inspiration. With the ready circulation of ornament prints by European artists, however, those images increasingly supplanted direct Asian prototypes. Highly stylized, deliberately “unnatural” chinoiserie motifs came to dominate 18th-century decorative arts, migrating across materials and workshops.14

Pagodas and Power

Chinoiserie wasn't confined to coffee pots or parlor walls—it reshaped whole landscapes. British architect William Chambers popularized pagodas in gardens, while royal patrons from Versailles to Brighton turned the style into architectural theater. From royal pleasure palaces to garden pavilions, chinoiserie became a mode of elite spectacle, often positioning racialized figures as aesthetic flourishes and collapsing cultural specificity into an artificial fantasy.

Digitally Reconstructed 3D Aerial view of the Porcelain Trianon, Palace of Versailles, France. Wikimedia Commons, user: Hervé Gregoire, CC BY-SA 4.0. Digitally rendered bird’s-eye illustration of Versailles’s Porcelain Trianon, showing five blue-and-white, porcelain-clad pavilions arranged around a central court, framed by symmetrical gardens, paths, and fountains.

The earliest grand experiment was the Trianon de Porcelaine at Versailles, built in 1670 for the king of France, Louis XIV, and his mistress, Madame de Montespan. Contemporary French accounts describe a pavilion sheathed in blue-and-white earthenware and studded with imported Chinese jars—even the floor was tiled.15 The building did not withstand the French winters and was demolished after just seventeen years, but the project heralded how royal architectural projects across Europe would start to take their inspiration from chinoiserie.

Detail of the Chinese Tea house at Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam, Germany, c. 1755-64. Wikimedia Commons, user: W. Bulach, CC BY-SA 4.0. In view are three gilded chinoiserie statues holding parasols and instruments, and gilded columns inspired by palm tree trunks. These are situated in a blue-green garden pavilion with a lanterned dome, but since this is a zoomed in view, we do not see the latter.

The Chinese Tea house at Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam, Germany, c. 1755-64. Wikimedia Commons, user: Kurt Kaiser, CC BY-SA 1.0. Daytime view of the blue-green Chinese Tea House at Sanssouci, a circular pavilion with a lanterned-dome, gilded columns inspired by palm trees and chinoiserie inspired golden statues placed around arched windows. A small signboard and bicycle sit by the entrance.

Seventy years later, the King of Prussia, Frederick the Great, applied the ongoing fashion for chinoiserie to his summer palace in Potsdam. His 1745 Chinese Tea Pavilion at Sanssouci Palace gleams with gold-plated sculptures of palm trees and “Oriental” musicians and servants—life-size figures modeled on European prints rather than lived realities. Inside, porcelain brackets, painted friezes, and a wraparound mural of invented “Chinese” scenery turn the simple act of drinking tea into an immersive pageant of cultural stereotypes.16

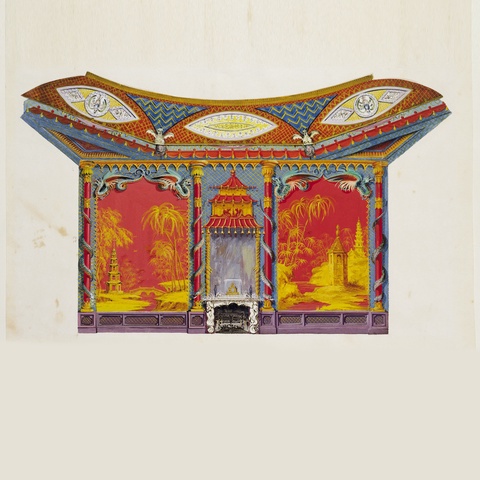

The stylistic trend continued into the nineteenth century. John Nash’s 1823 remodel of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, built initially for the British King George IV, fused Indian domes with Chinese interiors.17 The Music Room, for instance, is swathed in red painted walls, lit by lotus chandeliers, and rises to a dome of gilded dragons. Here, Indian and Chinese nature and culture blur into an extravagant vision of the East—one that served to flatter Britain’s imperial imagination as much as its artistic ambitions. Across these examples, chinoiserie boosted these opulent symbols of European power. Stylized figures, pagodas, and palm trees became props, transforming an imported idea of the East—its nature and its people—into ornaments of wealth and empire.

Varnishing Desire

European desire for East Asian luxury reached beyond porcelain to another coveted material: lacquer. Artists and collectors prized the deep, high-gloss surface of lacquerware and, whenever possible, repurposed and deconstructed entire panels to decorate interiors and furniture.

One of the most striking examples of this obsession is the Lacquer Room from the palace of the Frisian stadtholder in Leeuwarden, built before 1695 and now conserved at the Rijksmuseum. Part of the private apartments of the Frisian Stadtholder’s family, the room is lined with imported folding screens made out of Chinese Coromandel lacquer that were disassembled and reset as wall panels.18 Stripped of their original sequence, the scenes no longer tell a story; they function instead as a shimmering atmospheric backdrop.

Furniture makers followed suit. Some veneered cabinets were made with genuine lacquer, such as Adam Weisweiler’s drop-front desk. Others relied on japanning—a layered varnish technique that mimicked the depth and richness of true lacquer.19 This secrétaire by René Dubois features japanned panels with scenes after François Boucher’s chinoiserie-inspired prints of the Four Elements. Such japanned pieces, whether Dutch, English, or American, soon signaled refinement and status.

Even porcelain wasn’t immune to the trend. For a brief period, the Sèvres manufactory in France produced pieces painted to resemble lacquer, blurring the boundary between medium and source. As historian David Porter notes, “Eighteenth-century consumers do not seem to have concerned themselves . . . with the actual provenance of ‘exotic’ decorative goods, so long as they fulfilled their desired aesthetic purpose.”20

Lacquer’s aura lasted well into modernity. James McNeill Whistler’s famed Peacock Room (1876-77) wraps birds, blossoms, and gold leaf into an interior scheme meant to imitate Japanese lacquer. Now an icon of the aesthetic movement, it was intended to showcase the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland’s collection of Kangxi porcelain.21 In a sense, this interior comes full circle: Asian porcelain is staged within a European room restyled to look “Asian,” a layered translation of taste.

Lacquer continued to signify taste and distinction into the early 20th century, appearing even in fashion plates. In these examples, the technique has been removed many steps from its origins, its meaning rewritten for each era.

Disrupting Chinoiserie

From pavilions to coffee pots, European makers translated “the East” into a flexible design kit—one that could be printed, stitched, lacquered, or glazed onto nearly anything. In the process, chinoiserie didn’t just exoticize, it also depoliticized. It translated complex cultural traditions and imperial histories into instantly legible signs of luxury, novelty, and taste. In doing so, chinoiserie helped maintain a visual hierarchy in which the East was imagined, collected, and consumed—but rarely allowed to speak for itself.

Today, contemporary artists and institutions are revisiting this history. In the exhibition,Disrupt the View: Arlene Shechet at the Harvard Art Museums, a contemporary sculptor responds to objects from the permanent collection, including European porcelain with chinoiserie motifs. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie reframes early modern objects as evidence of colonial fantasy, racial caricature, and gendered desire, and includes works by contemporary artists such as Patty Chang and Yeesookyung that chart ways of reclaiming Eurocentric narratives.22

In revisiting chinoiserie, artists and scholars alike are asking: what does it mean to find beauty in something built on distortion? How might we hold both pleasure and critique in the same frame? And might the “unnatural” one day feel natural again?

J. Cabelle Ahn is an art historian and writer based in Brooklyn, New York. She received her PhD in History of Art and Architecture from Harvard University in 2024. A specialist in early modern French and Dutch art, she also writes on the history of the art market and on contemporary artists who challenge, revise, or reframe the Old Masters. In addition to exhibition catalogues and academic volumes, her writing has appeared in Master Drawings, The Art Newspaper, Artnet News, Observer, and Elephant.

Citations

Emmer, Pieter C, and Jos J.L. Gommans. The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600-1800. Cambridge University Press, 2020. Google Books, AJ Accessed 28 July 2025; Vink, Markus. Encounters on the Opposite Coast: The Dutch East India Company and the Nayaka State of Madurai in the Seventeenth Century. Brill, 2015. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/EncountersontheOppositeCoastTheDut/SaW8CgAAQBAJ. Accessed 28 July 2025.

View of the City of Raiebaagh in Visiapoer, India. Rijksmuseum, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/object/View-of-the-City-of-Raiebaagh-in-Visiapoer-India--7de6a426347657dd5620f5ed294875ec. Accessed 16 August 2025. Parts of the East India House was reconstructed in the late 1990s and the historic interior was the subject of a series of public events and workshops from 2023 to 2024. “Decolonial Dialogues@Humanities,” University of Amsterdam, https://www.uva.nl/en/about-the-uva/organisation/faculties/faculty-of-humanities/humanities-in-the-city/decolonial-dialogues-at-humanities/decolonial-dialogues.html. Accessed August 19 2025.

Sténuit, Robert. “Le 'Witte Leeuw'. Fouilles sous-marines sur l'épave d’une navire de la V.O.C. coulé en 1613 à l'île de Sainte Hélène.” Rijksmuseum Bulletin, vol. 25, no. 4, 1977, pp. 193-199, bulletin.rijksmuseum.nl/article/view/20941. Accessed 19 July 2025; Moon, Iris. Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie. Yale University Press, 2025, p. 43. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Monstrous_Beauty_A_Feminist_Revision_of/09VNEQAAQBAJ.

Rinaldi, Maura. Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade. Bamboo Publishing, 1989.

Madsen, Andrew D. and Carolyn White. Chinese Export Porcelains. Routledge, 2017. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Chinese_Export_Porcelains/dyEvDwAAQBAJ. Accessed 28 July 2025; Tuan, Hoang Anh. Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Relations 1637-1700. Brill, 2007. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Silk_for_Silver/qfGvCQAAQBAJ. Accessed 28 July 2025.

Johns, Christopher M. S. and Tara Zanardi. Intimate Interiors Sex, Politics, and Material Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Bedroom and Boudoir. Bloomsbury, 2023, pp. 63-64. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Intimate_Interiors/oHeoEAAAQBAJ. Accessed 28 July 2025; Harris, Dale. “Amalienburg: Reflections on Rococo.” T: The New York Times Style Magazine, 7 March 1993, www.nytimes.com/1993/03/07/t-magazine/amalienburg-reflections-on-rococo.html. Accessed 5 Aug 2025.

Reed, Marcia and Paola Demattè. China on Paper: European and Chinese Works from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Century. Getty Research Institute, 2011, pp. 141- 142. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/ChinaonPaper/6XGfPyVNvWkC. Accessed 25 July 2025.

Nieuhof, Johan. An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces. Translated by John Ogilby, also the publisher, 1669. Royal Collection Trust,

https://www.rct.uk/collection/1050938/an-embassy-ofnbspfrom-east-india-company-of-the-united-provinces-to-the-emperour. Accessed 12 August 2025; Spary, E.C. “The ‘Nature’ of Enlightenment.” In The Sciences in Enlightened Europe, edited by Jan Golinski, Simon Schaffer, and William Clark. University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 272-306. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/TheSciencesinEnlightenedEurope/ttGgd6mec1MC. Accessed 25 July 2025.

Miya Tokumitsu, “‘Chinese Arabesques’ by Jean-Baptiste Pillement and Anne Allen (ca. 1790–99).” Public Domain Review, May 29, 2024. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/chinese-arabesques. Accessed 10 August 2025; Maria Gordon-Smith, Pillement, Internationale per le Ricerche di Storia dell'Arte, 2006.

Sayer, Robert. Ladies’ Amusement; or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy. Robert Sayer, 1758, p. 4.

Edwards, Clive. Eighteenth-Century Furniture. Manchester University Press, 1996, p. 105. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/EighteenthCenturyFurniture/jMXYAAAAIAAJ

Stein, Perrin, “Boucher, Printmaking, and the Chinoiserie enterprise.” English version of “François Boucher, la gravure et l’entreprise de chinoiseries.” In Une des provinces du Rococo: La Chine rêvée de François Boucher, edited by Virginie Frelin and Vincent Bastien. Édition Faton, 2019, pp. 222-237. Academia, www.academia.edu/44263321/BoucherPrintmakingandtheChinoiserieenterpriseEnglishversion. Accessed 28 July 2025. See also: Perrin Stein, “Boucher's Chinoiseries: Some New Sources.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 138, no. 1122, September 1996, pp. 598-604. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/887244. Accessed 27 July 2025.

Munger, Jeffrey and Elizabeth Sullivan. European Porcelain in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yale University Press, 2018, pp. 5-7. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/EuropeanPorcelaininTheMetropolitan_M/YAxZDwAAQBAJ. Accessed 27 July 2025.

Honour, Hugh. Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay. J. Murray, 1961, p. 108. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/Chinoiserie/HH80AQAAIAAJ. Accessed 27 July 2025.

Zega, Andrew and Bernd H. Dams. “La Ménagerie de Versailles et le Trianon de Porcelaine : Un passé restitué.” Versalia: Revue de la Société des Amis de Versailles, no. 2. 1999, pp. 66-73. Persée, www.persee.fr/doc/versa1285-84121999num211002. Accessed 27 July 2025.

Shamy, Tania Solweig. “Frederick The Great's Porcelain Diversion: The Chinese Tea House at Sanssouci.” 2009. McGill University, MA Thesis, Department of Art History and Communication Studies. eScholarship@McGill, https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/h128nf59j. Accessed 28 July 2025; Jacobsen, Stefan Garrsmand. “Chinese Influences or Images? Fluctuating Histories of How Enlightenment Europe Read China.” Journal of World History, vol. 24, no. 3, 2013, pp. 623–60. Jstor, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43286029. Accessed 27 July 2025.

Loske, Alexandra. The Royal Pavilion, Brighton: A Regency Palace of Colour and Sensation. Yale University Press, 2025; Aldrich, Megan. The Craces: Royal Decorators, 1768-1899. John Murray, 1990.

Dorscheid, Jan, Paul van Duin, and Henk van Keulen. “The late 17th century lacquer room from the Palace of the Stadtholder in Leeuwarden, preserved in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.” in Investigation and Conservation of East Asian Cabinets in Imperial Residences (1700-1900), edited by Tatjana Bayerova, Martina Griesser-Stermschegg, Manfred Trummer, Manfred Schreiner, Elfriede Iby, Gabriela Krist. Böhlau Verlag, 2015, pp. 239-259. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Investigation_and_Conservation_of_East_A/gqulDAAAQBAJ. Accessed 21 August 2025.

Webb, Marianne. Lacquer: Technology and Conservation: A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology and Conservation of Asian and European Lacquer. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/LacquerTechnologyand_Conservation/rp5JklFUpacC. Accessed 1 August 2025.

Porter, David. Ideographia: The Chinese Cipher in Early Modern Europe. Stanford University Press, 2002, p. 136. Google Books, www.google.com/books/edition/Ideographia/YoFdUzZSe60C. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Merrill, Linda. The Peacock Room: A Cultural Biography. Yale University Press, 1988. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Peacock_Room/Ha4xwgfjbmoC. Accessed 1 August 2025.

Moon, Iris. Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie. Yale University Press, 2025.

J. Cabelle Ahn is an art historian and writer based in Brooklyn, New York. She received her PhD in History of Art and Architecture from Harvard University in 2024. A specialist in early modern French and Dutch art, she also writes on the history of the art market and on contemporary artists who challenge, revise, or reframe the Old Masters. In addition to exhibition catalogues and academic volumes, her writing has appeared in Master Drawings, The Art Newspaper, Artnet News, Observer, and Elephant.