Dust Deferred: The Invisible Care and Humility in Maintaining Our Spaces

By Sam Bennett•August 2023•15 Minute Read

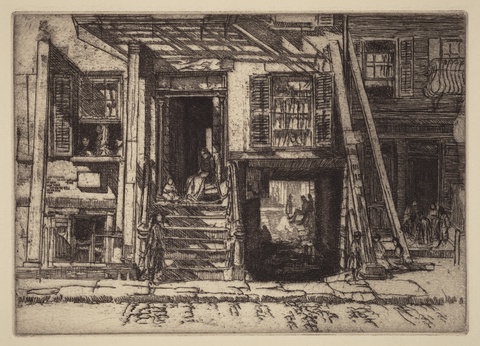

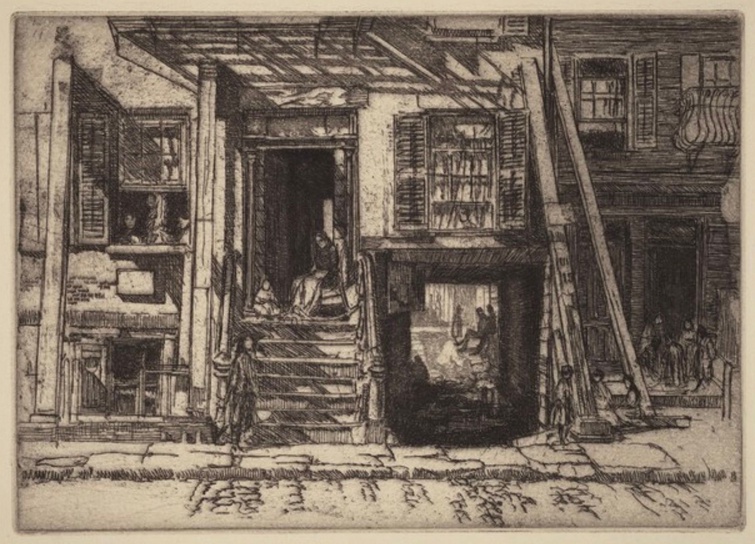

Charles Henry White, The Condemned Tenement, 1906. National Gallery of Art, public domain.

By considering dust and the humble broom, we can recognize the value of maintenance and reflect on our own responsibilities to care for and preserve the spaces we inhabit.

My Braun coffee grinder, passed down from my parents’ kitchen, stopped working suddenly. As a repair artist, I took it as an invitation to explore this little machine. I systematically removed each part and gingerly swept decades of old coffee grounds out of crevices with a soft brush. I carefully put it back together, plugged it in, and depressed the button. The grinder quickly whirred up to its usual speed.

While it certainly would have been easier to throw away the family coffee grinder and replace it, a small amount of care—clearing away forty years of particles—was all it took to extend its useful life. This got me thinking, how else does this pattern of neglect play out at a larger scale, in the built environment, in the world? Whose responsibility is it to care for our communal spaces, and what are the consequences when no one does? And how might these invisible practices of maintenance be documented and honored for future reference?

Demolition and Decay in New York

In New York City, countless buildings have been neglected throughout the city’s history. The etching above, completed in 1906 by Charles Henry White and titled The Condemned Tenement, gives a glimpse into the disrepair that can come from shoddy construction and poor upkeep, which eventually leads to abandoned or “mothballed” buildings, or complete demolition.1

The Pennsylvania Hotel, which I passed by every week on my way from Penn Station to Herald Square, was demolished in 2023. For 102 years, it had been one of the first structures you saw when you left the station—a space for travelers, conventions, and entertainment.

Wurts Bros. (New York, N.Y.), Hotel Pennsylvania, New York, 1860–1920 (approximate), The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. A photograph of the exterior of the Pennsylvania Hotel, outside of Penn Station in New York City.

It was deemed too pedestrian and denied landmark status in 2008. After the ownership changed to a company called Vornado, the once grand structure became known for bed bugs and peeling wallpaper. The Covid-19 pandemic sealed the hotel's fate, forcing it to close; demolition followed swiftly. The Pennsylvania Hotel is just one example of a repeating tragedy: maintenance deferred, vision squandered, buildings built with integrity reduced to dust.

The True Cost of Rebuilding Anew

Tearing down a structure to rebuild anew is often easier, quicker, and the most financially viable option. At face value, this viewpoint is easy to understand—good quality upkeep, repair, and refurbishment needs an upfront investment of time and effort. And many developers, architects, and designers ignore the fact that the human health, environmental, and cultural costs are much higher. Without intentional acts of maintenance, an accumulation of dust, grime, and wear break down our spaces. New York City cannot afford to ignore these daily practices, as the city and state continue to grapple with a housing crisis.2

Within the global construction industry alone, its annual embodied carbon is responsible for 11% of total greenhouse gas emissions from new building materials.3 Today, new buildings are designed with an expiration date. Many luxury or market rate apartments have a renovation plan in place before the building is built—commonly a seven, ten, or 15-year schedule. This is planned obsolescence at a large scale. These short timelines imply that the budget will be spent on future new materials and installation, rather than on maintaining the current space and using higher quality, long-lasting materials. Because of this quick turnover, initial material choices are typically cheaper, break down more easily, and eventually end up in a landfill. Although higher quality materials would increase costs upfront, a clear and consistent maintenance plan would extend the building’s life, reduce waste, and reduce costs in the long run.

On the contrary, most affordable housing projects do not have a refresh or renovation schedule, so it requires a rigorous practice of care to give a space longevity. Without a consistent maintenance plan in place, apartments become untenable and fall into disrepair. For instance, in 2018, the New York Public Housing Authority faced a daunting backlog of more than 170,000 open work orders for repairs, almost double the number housing officials said they could actually manage.4 A resident with a damaged wall, for example, would wait an average of 100 days for a plasterer and three months more for a painter to finish the job.5 The Fulton Houses and Elliott-Chelsea Houses in Manhattan are recent cases where the City decided it was more cost effective to tear them down, which will relocate residents of 2,000 apartments.6

Disconnection and Inequities in Care

Sam Bennett, Brooklyn Super Sweeping Trash, 2023. CC BY-NC-SA. Super sweeps up trash on a Monday morning in Flatbush, Brooklyn.

In a recent interview in The New York Times Magazine, ecologist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks about a world often controlled by those who have a “master-of-the-universe” perspective. "People with that perspective were not raised with the word 'humility' in their vocabulary as a good thing," she says. "Humility in Western culture is to be meek and mild and dispossessed. In Potawatomi ways of thinking, we uphold humility. Edbesendowen is the word that we give for it: somebody who doesn’t think of himself or herself as more important than others. What that means is that everybody is as important as you are, and what that creates is this sense of vitality and community and family… Humility that brings that sort of joy and belonging as opposed to submission."7

In New York, it’s common to see trash loosely strewn around sidewalks, parks, and subways platforms. But whose responsibility is it to care for these civic spaces? Somehow, many of us have decided it is not our job to clean up after ourselves and to maintain our public spaces for each other. Perhaps we lack the humility. This thinking creeps into our communal spaces in private property, too, affecting the cleanliness and maintenance of the lobbies, hallways, stairwells, and elevators of our apartment buildings. When much of the city feels run down, it can be hard to decipher if it is just our physical environment that incites apathy or the “master of the universe” perspective, or both. I would argue that the daily chores of the supers who care for our buildings often go unnoticed. The shoveled sidewalks before one wakes, a broken pipe needing attention, prepping an apartment for a new tenant. The invisibility of care allows the rest of the community to care less.

Legacy Pollutants

Not only are caretakers faced with hard manual labor, but their rigorous practice of maintenance exposes them to dust, grime, and cleaning chemicals almost every day. According to the National Domestic Workers Alliance, there are over 200,000 domestic workers in New York City alone. 94% are women, 78% were born outside of the United States; 38% are Hispanic/Latinx, 27% Black (non-Hispanic), and 18% Asian.8

In addition, according to architectural firm Perkins&Will, the chemicals found in our dust, known as legacy pollutants, disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income families, due to decades of positioning their homes and schools close to industrial sites, using cheap building materials, and poor maintenance.9

Undisclosed chemical ingredients are widely used in our building materials and consumer products from your couch to your carpet. We ingest these chemicals without consent. They get into the air we breathe, and they even migrate into the dust we unknowingly swallow all day long. In the United States, people ingest an average of 20 milligrams of dust each day.10

Some do not need sophisticated research in labs to realize this. In 1907, James Murray Spangler, a janitor in Canton, Ohio, concluded that his asthma could only be alleviated with a better type of carpet sweeper. Using an old fan motor, a soapbox, a broom handle, and a pillowcase, he created the first electric vacuum cleaner. He eventually sold the patent for his invention to his cousin's husband, William H. Hoover.11

Community Care in Mexico

While traveling in Mexico City in the summer of 2019, I was struck by the colors, the trees, the flowers, and the food on every corner. The city sounds also caught my attention: a whistle from a sweet potato cart in the evening, the scrap metal song that blared from old trucks puttering on the streets, and the bell that rang to alert neighbors it was time to bring their trash out. Unlike in New York, trash is not allowed to be left out on the sidewalk for pickup. Although the bell sounds jovial, Mexico City’s sanitation system is problematic. One must be available to take out the trash, and not all trash is taken. In many instances, unofficial sanitation workers are tipped in exchange for taking restricted trash.12

Sam Bennett, Collection of Brooms Photographed in Oaxaca City, 2023. CC BY-NC-SA. A selection of photographs of brooms documented in Oaxaca City, Mexico.

What continued to catch my eye day after day were the brooms: Leaning against the wall, a tree, a corner, waiting to be used. Evidence that care was part of people’s daily practice. A few years later, in November 2022, while in Oaxaca City, Mexico, I began documenting brooms wherever I spotted them. By the third week, I had collected photographs of over a hundred brooms, lingering outside stores and in interior corners.

When I visited the Centro Cultural Comunitario Teotitlán del Valle, I came across this word: tequio. Tequio is when the community comes together for a day of service. The word tequio comes from the nahuatl or Aztec word tequitl, which is defined as "work" or, a more beautiful definition, "tribute." I was very moved by this idea and it stuck with me.

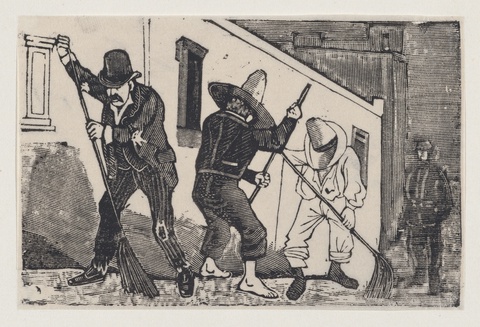

In the etching, A group of men sweeping the street, artist José Guadalupe Posada symbolizes the various people of Mexico through their dress. There is a man in a bowler hat, a recent immigrant in white cotton, and a man in the short, tight, dark jacket typically worn by the rich.13 This unlikely grouping looks forced and perhaps even foreboding, with an officious man in the shadows on the far right. But perhaps the point of Posada’s odd arrangement is to encourage the audience to wrestle with the various classes' responsibilities to the greater good of the community.

Museums Making Care Visible

Museums, too, can play a role that highlights and honors maintenance. Through a collection of work or one-off pieces, a museum can encapsulate a moment in time, create conversations and comparisons, and perhaps ultimately reveal something forgotten or elevate something ignored. Below are examples of objects or commissioned works that do so.

The decorative arts collections within museums hold a plethora of objects, many of which celebrate repair. For instance, this Chinese bowl at the Walters Museum is mended in a way that highlights (rather than hides) the damage. Using a Japanese repair technique called kintsugi, broken ceramics are glued back together using urushi lacquer and covered with metallic powder. This visible repair plays into the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, a belief in the beauty of imperfection. Another example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a darning sampler. Darning is a technique used to repair torn or moth-eaten textiles. This silk sampler was created to show off various techniques that could be used to match future textiles being repaired. One can view a whole plethora of samplers in this darning collection. Contemporary darners like Celia Pym have taken inspiration from these samples and adopted visible mending practices, like kintsugi, highlighting rather than hiding the fixes.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles elevated the lowly menial tasks of cleaning by declaring herself a maintenance artist. She created the Maintenance Art Manifesto 1969! Proposal for an exhibition called "CARE." An artist first and foremost, she then married and had children. This shifted her practice from art to maintaining the life of a child. People assumed if she was an artist, she couldn’t be a mother and vice versa. She was angered by the status given to her position as a mother. If she was in her studio she wondered about the care of her child, if she was with her child, she wanted to work on her art. Yet, as a maintenance artist, she embraced the duality.

In 1973, she mopped the front of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Four hours later, she marked the task with her signature. She instantly changed the cultural value of her work. Here she is shedding light on the invisible workers who clean out of sight, exposing the action of their work during the open hours of the museum, elevating their care for all to see.

And a final example: a lowly broom would likely be deemed ordinary and ignored, if it were not held in the Smithsonian Museum of African American History’s collection. This particular broom was used by members of the Newborn Community of Faith Church to clean up debris from Baltimore protests after Freddie Gray died in police custody. This humble artifact (one of many) signifies layers of care: protestors caring for justice, community members caring for their city.

These objects and actions collected and cared for within these institutions help to emphasize the importance of maintenance.

As the Dust Settles

In an essay titled “Pulverulence” by Steven Connor in Cabinet, he states, “We strive with dustpan and vacuum cleaner to separate ourselves from our dust, but here the dust is a way of separating objects from their silhouettes just as the incandescent cinders turned the bodies of the Pompeians into their own inverted images or moulds. The soot effects a fall-out photography, a soft, spectral frottage, or finger-painting of the space.”14

Simply put, dust shows what we have neglected.

But there are moments that require the dust to be dusted. Like when the light catches a forgotten surface, and the dust can no longer be ignored.

They are the accumulation of the experiences that have happened in our homes, the windows leaking particles from the outside in, our skin cells shedding, and our hair falling from our heads. Eventually, all we will be is dust, swept or picked up by the wind, carried into a corner, the ocean, the atmosphere.

I won’t be here anymore. I’ll be everywhere, grateful for those who continue to care.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to express my gratitude to the Lenape people, the original stewards of this land that I am writing on, here in Brooklyn, New York.

I am also grateful to five people: Andrea Sosa Fontaine for our chats about slowness in the interior, Rachel Smith for her hands as we darn and share repair knowledge to others together, Leila Behjat for putting soul into our nitty-gritty building research, Chuchi for doing our laundry, and my mom who is never without a rag, taught me how to dust, and always emphasized how every job is important, including sanitation work.

Sam Bennett is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. She is a repair artist, ethnographer, and designer with expertise in the fields of space, materials, and objects. She believes in slow research that minimally impacts our planet and advocates for human well-being. Her personal research is focused on consumerism, accumulation, and repair of objects in the domestic space and in the waste stream. She is the founder of The Things We Keep, a collection of stories about people’s most special things. She also runs Clever/Slice, a space for creatives to share in-progress work, while dismantling the classic critique. Most recently she co-created Repair Shop with Rachel Smith, which explores the line between object-based mending practices and other modes of “making do.” Currently, Sam is a sustainability strategist at Hyloh, collaborating on projects focused on New York City’s reuse systems. In 2022, she was a Maintainers Movement fellow and completed residencies at Pocoapoco in Oaxaca and LMCC on Governors Island. In her free time, she darns and writes letters on one of her five typewriters.

Citations

Behjat, Leila and Sam Bennett. “Governors Island: Balancing the Past with the Future.” Maintainers, 7 December 2022, themaintainers.org/nicole-governors-island-balancing-the-past-with-the-future/. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Negret, Marcel et al. “Meeting Housing Need and the Pace of Growth in New York State.” Regional Plan Association, RPA Lab, 19 December 2022, https://rpa.org/latest/lab/meeting-housing-need-and-the-pace-of-growth-in-new-york-state. Accessed 4 August 2023.

“Why the Building Sector?” Architecture 2030, 2030dev-architecture-2030.pantheonsite.io/why-the-building-sector/. Accessed 4 August 2023.

“Nycha Metrics.” New York City Housing Authority - NYCHA Metrics, NYC Housing Authority, eapps.nycha.info/NychaMetrics. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Negret.

Zaveri, Mihir. “To Improve Public Housing, New York City Moves to Tear It Down.” The New York Times, 21 June 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/06/20/nyregion/public-housing-demolish.html. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Marchese, David. “You Don’t Have to Be Complicit in Our Culture of Destruction.” The New York Times, 30 January 2023, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/01/30/magazine/robin-wall-kimmerer-interview.html. Accessed 04 Aug. 2023.

“New York City Domestic Work Factsheet.” National Domestic Workers Alliance, 4 June 2021, www.domesticworkers.org/membership/chapters/we-dream-in-black-new-york-chapter/nyc-care-campaign/new-york-city-domestic-work-factsheet. Accessed 4 August 2023.

“Inhabit: Love in the Time of PFAS.” Inhabit Podcast, Perkins&Will, 29 August 2022, www.inhabit.perkinswill.com/home-2/series1/episode-02-love-in-the-time-of-pfas/. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Lerner, Sharon. “Indoor Dust Contains PFAS and Other Toxic Chemicals.” The Intercept, 14 April 2021, www.theintercept.com/2021/04/14/pfas-toxic-chemicals-indoor-dust/. Accessed 4 August 2023.

“Hoover Upright Vacuum Cleaner.” National Museum of American History, www.americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_704090. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Villagran, Lauren. “Garbage for the Future.” Next City, 16 July 2012, nextcity.org/features/garbage-for-the-future. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Gretton, Thomas. “Posada and the ‘Popular’: Commodities and Social Constructs in Mexico before the Revolution.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 17, no. 2, 1994, pp. 32–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360573. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Conner, Steven. “Pulverulence.” Cabinet Magazine, Fall 2009, pp. 71, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/35/connor.php. Accessed 23 August 2023.

Sam Bennett is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. She is a repair artist, ethnographer, and designer with expertise in the fields of space, materials, and objects. She believes in slow research that minimally impacts our planet and advocates for human well-being. Her personal research is focused on consumerism, accumulation, and repair of objects in the domestic space and in the waste stream. She is the founder of The Things We Keep, a collection of stories about people’s most special things. She also runs Clever/Slice, a space for creatives to share in-progress work, while dismantling the classic critique. Most recently she co-created Repair Shop with Rachel Smith, which explores the line between object-based mending practices and other modes of “making do.” Currently, Sam is a sustainability strategist at Hyloh, collaborating on projects focused on New York City’s reuse systems. In 2022, she was a Maintainers Movement fellow and completed residencies at Pocoapoco in Oaxaca and LMCC on Governors Island. In her free time, she darns and writes letters on one of her five typewriters.