The Dutch East India Company’s Colonial Trade and Plunder

By Reina Gattuso•June 2022•14 Minute Read

Unknown, Chest with Nine Bottles, c. 1680–1700. Rijksmuseum. Many keldertje, or small chests, are made of materials originating from the areas that the Dutch colonized and were often given as gifts to dignitaries of those nations.

The Dutch East India company built an empire on the spice and textile trades. As the largest corporation in human history, they shaped modern business as we know it. And they forever changed Asian and European art.

Introduction

When Dutch artist Simon Fokke created this allegorical etching of the Dutch East India Company in the mid-1700s, the corporation was literally sitting pretty.

Fokke depicts the Dutch East India Company, called the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), as an enthroned maiden ruling over a pile of riches. Behind her, the personified figure of Freedom holds a banner with the VOC logo.

The Dutch commissioned the VOC logo to adorn textiles, plates, and other luxury products. It did not signify freedom for the millions of people who lived under Dutch colonial rule.

The Dutch government formed the VOC in 1602. At its peak, the Company had 57,000 employees, 150 merchant ships, and a private military force with 40 warships and 10,000 soldiers.1 2 The VOC had a greater stock market valuation than any other company in human history.3

At its most powerful, the VOC controlled major ports in what are now Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and China. Following the Company’s dissolution in 1799, the Dutch government directly ruled Indonesia for almost 150 years. The Dutch crown also established the Dutch West India Company, which colonized the Americas.4

Fokke’s allegory reflects the VOC’s racist ideology. In the lower right, racially caricatured Asian and African people lay goods at the VOC’s feet. This implies that colonized people existed for the sole purpose of supplying the empire with resources and labor.

In reality, rulers, artists, and merchants across Asia traded with the VOC to gain personal wealth, advantages over adversaries, or political favor. If they did not trade with the VOC willingly, however, the company forcibly extracted wealth and labor. The Dutch East India Company committed mass brutality on a scale the Dutch are only now beginning to acknowledge.5

Both Asian and Dutch artisans who participated in this trade developed new textile, ceramic, and other artistic styles. Artists displayed incredible ingenuity and made works of stunning beauty.

At the same time, the VOC’s operations depended on economic and military domination. By controlling craft production and trade, the Dutch created captive markets they could exploit. This, in turn, allowed them to wrest and maintain political control, notably in Indonesia. By tracing stylistic changes in Dutch and Asian goods, we can understand how the Dutch used trade as a means of power.

An Empire Built on Spices

For most of the medieval period, the Dutch were a minor, regional trading power in the Baltic Sea. Their path to colonial dominance was paved with spices.

Europeans Enter the Maritime Spice Trade

Dating back to the ancient Greeks, Europeans craved spices from tropical Asian climates. People in the Malabar coast of India, Sri Lanka, and the Molucca Islands of Indonesia grew coveted pepper, cinnamon, and nutmeg.

For thousands of years, Austronesian seafarers controlled Southeast Asian trade. Central Asian and Arab merchants ran the overland spice route as far west as the Mediterranean. In the medieval and early Renaissance periods, Venetian and Genoese merchants disseminated these goods throughout Europe.

In the late 1400s, state-sponsored Spanish and Portuguese traders established a direct sea route to Asia around the southern tip of Africa. This cut out Asian intermediaries. In 1595, Dutch merchants organized their first voyage to Indonesia. The Dutch government chartered the VOC in 1602, granting it a monopoly over Asian trade.6

The Dutch battled the Spanish, Portuguese, and English to control sea routes. In Battle for the Gold Staff (Dominion of the World), a 17th-century allegorical painting, Dutch artist Willaerts depicts European powers fighting over a golden staff representing maritime dominance.

In 1619, the Dutch seized Jayakarta (modern-day Jakarta) from the Banten Sultanate. They renamed the city Batavia. Colonial Batavia became the VOC’s base in Asia. It connected them to the nearby Moluccas, the only place in the world that grew nutmeg.

In the 1600s, the VOC dominated the European nutmeg, pepper, and cinnamon trades. This led to astronomical profits for company shareholders.

Belgian divers found the underwater wreck of a VOC ship, the Witte Leeuw, or White Lion, in 1977. The ship sank during a conflict with the Portuguese in 1613. The ship still contained spices and ceramics, including the loose pepper above.7

Elite Europeans channeled the vast wealth brought by the spice trade into luxury goods.

One such costly item is this silver spice box from the Dutch city of Middelburg, an important VOC port.8 It would have held luxurious spices such as nutmeg and cinnamon. The box celebrates colonial wealth both in its design and materials. It is a model of the Mauritius, a Dutch ship that traveled to Indonesia in an early trade expedition.

The VOC Textile and Ceramics Trade

The Dutch entered into a long-established system in which Asian traders exchanged spices for textiles, ceramics, and precious metals.

The VOC commissioned textiles from India, particularly from the Coromandel Coast. They also traded ceramics with China and Japan. The VOC established a trade center at the Japanese island of Dejima. They became the only European power with whom Edo-era Japanese monarchs permitted trade.9

Possibly to gain a special trade dispensation from an Asian ruler, VOC officials commissioned this bottle and box set, called a keldertje. Batavian artists made the box’s wood construction and silver fittings. Japanese Kakiemon porcelain artists made the bottles. The Dutch commissioned the work with a white and blue color scheme, which was unusual for Kakiemon. This shows how the VOC influenced Japanese artistry. The bottoms of the bottles have the VOC seal, reminding the recipient of the company’s reach.10

Indonesian elites coveted Indian textiles. These textiles sometimes had religious motifs. Indonesian families treasured these textiles, handing them down as heirloom spiritual objects. The Dutch entered into this preexisting trade. They used precious Indian textiles as prestige gifts to help gain access to Indonesian spice markets.11

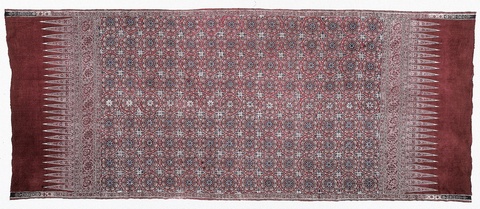

Artists on the Coromandel Coast of South India made this dyed cotton piece in the mid-1700s. The VOC likely traded or gifted it to an Indonesian. Sumatran people often wore this kind of cloth as a tapis, or hip wrapper.12

The Dutch also commissioned and imported textiles for the European market. Indian textile artisans adapted their work to suit both Indonesian and European tastes.

A VOC officer likely commissioned a South Indian workshop to make this chintz palampore. The artist decorated the cloth with the Amsterdam coat of arms. This is the only known chintz that bears a city’s coat of arms.13

Artistic Exchange and Colonization

Trade between Europeans and Asians produced a lively artistic exchange. Asian artists adapted and transformed European styles, and vice versa. But this trade also reflected power dynamics between the Dutch and various local rulers.

Japan retained their full autonomy from European colonialism, meaning they could reap economic benefits from the trade. The Dutch wrested partial colonial control over Formosa (modern-day Taiwan) in the 1600s, but were ousted in 1668. As a result, Chinese elites retained autonomy, at least until Britain and France forced trade and territorial concessions following the Opium Wars.14

In Indonesia, however, the VOC was an occupying power. From the 1600s to Indonesian independence in 1945, Dutch colonizers murdered upwards of one million Indonesian people for Dutch economic and political gain.15 16 17

In India, the Dutch controlled key ports rather than vast territories. The British East India Company eventually seized control of most of the subcontinent, annexing India in 1858.18

We need to take the context of colonial violence into account when we consider the interactions between Dutch and Asian styles. Was Dutch artists’ adoption of Asian styles an act of exchange, aesthetic imperialism, or both?

A Dutch craftsman made this chest between 1700 and 1710. The maker attempted to copy Chinese and Japanese lacquered wood chests. The shapes of the buildings and the figures’ long robes are a European imitation of Japanese and Chinese porcelain motifs.

Look closer, however, and you’ll find that the artisan also included Native American figures, adapted from English colonial engravings. The artist used feathered headdresses to signify Native Americans, reflecting a European caricature of Indigenous people.19 The iconography on this chest embodies a racist, colonial mindset in which European people viewed Asian and American indigenous people as generic and interchangeable.

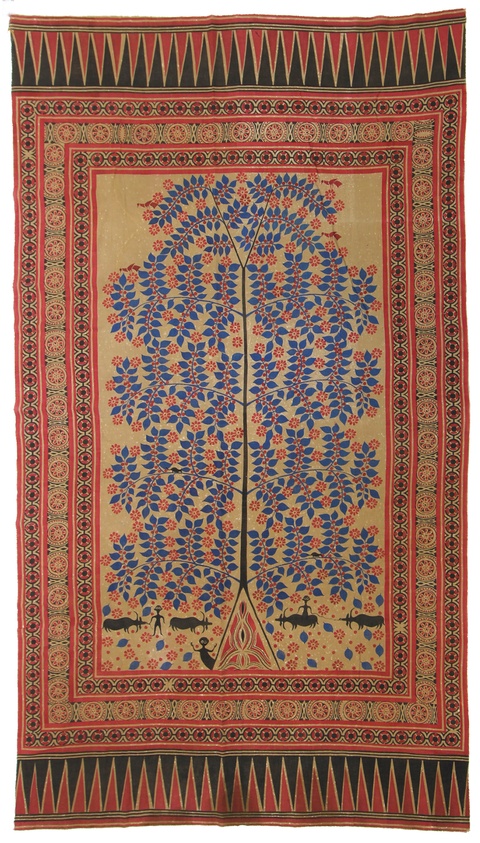

This ceremonial Maa cloth is another example of syncretism and cross-cultural influences. The Toraja communities of central Sulawesi, now Indonesia, displayed Maa cloths for ceremonial occasions.23 24 They originally imported the fabrics from India.25 This Dutch example is a machine-woven printed cotton that mimics both Indian and Indonesian designs.

The sawtooth at either end of the cloth is an Indonesian batik motif called tumpal. Indian weavers often included tumpal, and the motif of flowers enclosed in the border, in pieces for Indonesian export.26 The central design is a tree of life, a common motif across cultures, including in India.27 Indian weavers adopted European-style tree of life motifs in designs for the European market.28

In this Maa cloth, Dutch designers have incorporated local Toraja elements into the tree of life, specifically in the people, buffalos, and mountain at the bottom of the image.29

By the early 1800s, American cotton—produced through the enslaved labor of Black Americans—had displaced Indian cotton in the global market. European powers, led by the British, developed a mechanized textile industry.30

European powers sold American cotton cheaply to people they colonized in Asia and Africa. This rapidly impoverished the Indian textile industry.31 The Dutch similarly cut out Indonesian and Indian artisans to flood the Indonesian market with industrial printed cottons.32

Many scholars argue that European powers exploited natural resources while stunting industrialization in their colonial holdings as a means of maintaining control.33 34 When viewed through this lens, we can see how European imitation of Indian and Indonesian textiles contributed to colonial domination.

The Dutch Art Establishment Contends with Colonialism

The Dutch government dissolved the VOC in 1799. The Dutch continued to directly rule Indonesia until the Indonesian Revolution won independence in 1949. They surrendered their last Indonesian colonial holding in 1962, but retained colonial or semi-colonial dominance over several Caribbean islands.35 36

The VOC’s brutal extraction of labor and resources from colonized and enslaved peoples funded the art of the Dutch Golden Age. The Rijskmuseum, the national art museum of the Netherlands, holds thousands of works related to Dutch colonialism.

In 2022, the Rijksmuseum staged REVOLUSI!, an exhibition on the Indonesian Revolution, that recontextualized many of the colonial objects in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Indonesian artist Timoteus Anggawan Kusno created an installation addressing this legacy for the exhibition titled Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari, or (Wounds and Venom I Carry as I am Running).

Kusno removed the Rijksmuseum’s portraits of Dutch colonial officials and displayed their emptied original frames. He placed Indonesian pro-independence banners overhead. Indonesian revolutionaries carried these banners into battle against the Dutch, who captured them and stored them in the Rijksmuseum.

“Some flags have prayers stitched, reflections of the spirit, and the yearning to be free from colonial oppression,” writes Kusno.37 We see this yearning reflected in Kusno’s composition. Below, the mighty have fallen, removed from their frames. Above, the revolutionaries’ hopes fly.

This revolutionary yearning is displayed in what remains a temple to colonial loot, in a deeply unequal world. “All this leaves us questions about the long unfinished business of the colonial matrix of power,” Kusno writes. “Where do we stand now?”38

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Suggested Readings

Atsushi, Ota. “The Dutch East India Company and the Rise of Intra-Asian Commerce.” Nippon, 18 September 2013, www.nippon.com/en/features/c00105/. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Nath, Gopika. “Tree of Life: Decoding a Profoundly Symbolic Ancient Motif.” Verve, 27 September 2016, www.vervemagazine.in/arts-and-culture/decoding-the-tree-of-life-motif-and-relevance-in-art-fashion. Accessed 21 March 2022.

McGivern, Hannah. “Revolutionary Rijksmuseum exhibition reckons with Dutch colonial conflict in Indonesia.” The Art Newspaper, 2 March 2022, www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/02/revolutionary-rijksmuseum-exhibition-reckons-with-dutch-colonial-conflict-in-indonesia. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Citations

“Dutch East India Company.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DutchEastIndiaCompany#citeref-ReferenceA_106-0. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Lucassen, Jan. “A Multinational and Its Labor Force: The Dutch East India Company, 1595-1795.” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 66, 2004. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27672956.

Planes, Alex. “A History of Ridiculously Big Companies.” The Motley Fool, 1 October 2018, https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2012/08/22/a-history-of-ridiculously-big-companies.aspx. Accessed 9 May 2022.

“Dutch colonization of the Americas.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DutchcolonizationoftheAmericas. Accessed 21 March 2022.

McGivern, Hannah. “Revolutionary Rijksmuseum exhibition reckons with Dutch colonial conflict in Indonesia.” The Art Newspaper, 2 March 2022, www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/02/revolutionary-rijksmuseum-exhibition-reckons-with-dutch-colonial-conflict-in-indonesia. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Atsushi, Ota. “The Dutch East India Company and the Rise of Intra-Asian Commerce.” Nippon, 18 September 2013, www.nippon.com/en/features/c00105/. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“White Lion (16510).” De VOC site, www.vocsite.nl/schepen/detail.php?id=11720. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Middelburg in the Dutch Golden Age.” Netherlands Board of Tourism & Conventions, www.holland.com/global/tourism/destinations/provinces/zeeland/middelburg-in-the-dutch-golden-age.htm. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“The Dutch East India Company and the Rise of Intra-Asian Commerce.”

Hond, Jan de and Menno Fitski. A Narrow Bridge: Japan and the Netherlands from 1600. Rijksmuseum, 2016, p. 122. library.rijksmuseum.nl/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=253771. Accessed 21 March 2022

“Patolu with Elephant Design.” The Met, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77871. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Oversize Hip Wrapper (tapis).” The Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2000.28. Accessed 9 May 2022.

“Bed Cover.” Rijksmuseum, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/BK-1966-20. Accessed 9 May 2022.

Fisher, Max. “Map: European colonialism conquered every country in the world but these five.” Vox, 24 February 2015, https://www.vox.com/2014/6/24/5835320/map-in-the-whole-world-only-these-five-countries-escaped-european. Accessed 9 May 2022.

Toebosch, Annemarie. “Dutch Memorial Day: Erasing People After Death.” The Conversation, 15 Aug. 2018, https://theconversation.com/dutch-memorial-day-erasing-people-after-death-97236. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Tasevski, Olivia. “The Dutch are Uncomfortable with Being History’s Villains, not Victims.” Foreign Policy, 10 August 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/10/dutch-colonial-history-indonesia-villains-victims/. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Raben, Remco. “On genocide and mass violence in colonial Indonesia.” Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 14, no. 3-4, September-November 2012. Taylor and Francis, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14623528.2012.719673. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Wolpert, Stanley A. “British raj.” Britannica, 8 September 2020, www.britannica.com/event/British-raj. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Cabinet with Chinese and American Motifs.” The Walters Art Museum, art.thewalters.org/detail/22673/cabinet-with-chinese-and-american-motifs/. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Mix, Elizabeth. “Appropriation and the Art of the Copy: Cultural and Transcultural Appropriation in the Colonial Period.” Choice, vol. 52, no. 9, May 2015. American Library Association, https://ala-choice.libguides.com/c.php?g=372675&p=2520113. Accessed 8 April 2022.

“Plate Depicting a Lady with a Parasol.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/205078. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Dish with Parasol Ladies.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49423. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Ceremonial cloth and sacred heirloom [mawa or ma'a].” National Gallery of Australia. Google Arts and Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/ceremonial-cloth-and-sacred-heirloom-mawa-or-ma-a-traded-to-toraja-people-sulawesi-indonesia/WQF8iuOzppgWuQ?hl=en. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Guy, John S. “Commerce, power, and mythology: Indian textiles in Indonesia.” School of Oriental and African Studies Newsletter, vol. 15, no. 42, March 1987, Taylor and Francis, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03062848708729660?journalCode=cimw19. Accessed 9 May 2022.

“Maa cloth.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/651331. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Maa cloth.”

Nath, Gopika. “Tree of Life: Decoding a Profoundly Symbolic Ancient Motif.” Verve, 27 September 2016, www.vervemagazine.in/arts-and-culture/decoding-the-tree-of-life-motif-and-relevance-in-art-fashion. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Palampore.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448178. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Maa cloth.”

Brooks, Chris. “Cotton in World History: India, Britain and America.” The Center for World History, UC Santa Cruz, 2008, humwp.ucsc.edu/cwh/brooks/cotton/India,Britainand_America.html. Accessed 21 March 2022.

“The Fabric of India: Textiles in a Changing World.” Victoria and Albert Museum, www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/the-fabric-of-india/textiles-in-a-changing-world/. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Van der Eng, Peter. “Why Didn't Colonial Indonesia Have a Competitive Cotton Textile Industry?” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 47, no. 3, 30 October 2012, pp. 1019-1054.

Haworth, Whitney. “Imperialism and De-Industrialization in India.” Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/whp-1750/xcabef9ed3fc7da7b:unit-3-industrialization/xcabef9ed3fc7da7b:3-2-global-industrialization/a/imperialism-and-de-industrialization-in-india-beta. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Lowes, Sara, and Eduardo Montero. “Lasting Effects of Colonial-Era Resource Exploitation in Congo: Concessions, Violence, and Indirect Rule.” VoxDev, 11 January 2021, https://voxdev.org/topic/institutions-political-economy/lasting-effects-colonial-era-resource-exploitation-congo-concessions-violence-and-indirect. Accessed 8 April 2022.

“Dutch Empire.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DutchEmpire#Decolonization(1942%E2%80%931975). Accessed 21 March 2022.

“Caribbean Netherlands.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caribbean_Netherlands. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Kusno, Timoteus Anggawan. Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari, 2022. See www.takusno.com/luka-dan-bisa-kubawa-berlari/. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Kusno.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.