Sonic Struggles: Plunderphonics and A Case for Immaterial Repatriation

By Brianna Beckford •August 2023•23 Minute Read

William Sydney Mount, The Power of Music, 1847. A Black laborer smiles in pleasure listening to a fiddle tune coming from inside the barn.

Plunderphonics calls for radical creative liberties in a pop culture-dominant globe, but cultural appropriation and theft follow in a decades-long tradition of abusing Black musicians. Can the immaterial be repatriated?

Repatriating art objects looted during colonial times has picked up steam in the last decade. Some western museums and collections are now scurrying to decolonize and realign themselves with the increased calls for acknowledging not only the cultures their art objects come from, but also the means through which they came into their possession. Often, these art objects reaffirm the existence of an individual maker or collective collaboration. These artworks become essential to defining the cultural life of the lived, and the living.

Contained within cultural items are histories of strife, slices of everyday life, and the many events that fall between tension and success. Specific musical knowledge and the music made with it are also cultural objects. For example, Luis Dias, a Dominican musician who worked all through a post-Trujillo Dominican Republic, called the different genres of music expressing the ensuing conflict la lucha sonora.1 Clearly this sonic struggle holds cultural weight. Black American musical history in particular is inextricable from the history of its people, through the diaspora and into the United States. The sonic struggle of black people in America is represented through physical ephemera, but are the recorded notes, beats, techniques themselves heritage objects and artifacts?

The push to decolonize the museum structure is novel for the 21st century, but cultural pilfering never stopped at physical objects. How can we reclaim a voice, or a beat, in the age of access?

Creating Plunderphonics

Plunderphonics is a word coined by John Oswald in 1985. During his presentation at the Wired Society Electro-Acoustic Conference in Toronto, Oswald defined the genre, its tenets, and defended its praxis. An experimental sound artist at the time, Oswald pulled much of his thinking surrounding music and copyright from personal experience participating in soundwalks.2 For John, pop music became intermingled with the recorded environment; the sound of church bells blended with the recent singles of Dolly Parton and Madonna’s exemplified the integral part to the experimental sound collage definition of plunderphonics. His own productions under this new genre include repeated segments from one or more songs, strung together to create a stuttering, sometimes explosive song. Songs aren’t necessarily remixed; broken into many pieces, the odds and ends of a record are sorted back into a scrambled sequence that maintains the audio’s signature. This is why the challenging aspect of copyright underpins plunderphonics. Broken down into sections in his essay, as well through pages of his website, John Oswald's argument championing plunderphonics focuses on questioning these copyright laws in the modern day.3

The Argument for Sound Collages

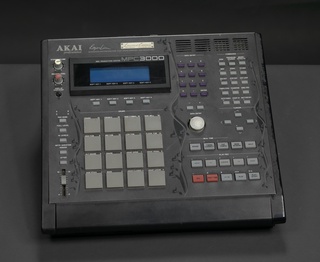

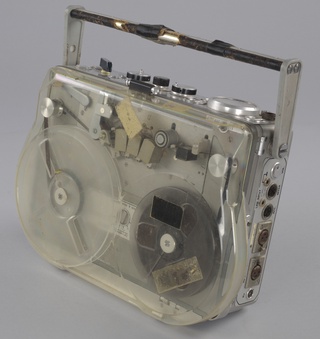

In the 80s, a heat wave of hip-hop and rap ignited hot shifts in musical culture. Music consumers found their technological expertise flourishing in this atmosphere as the pathway to becoming producers became much more navigable. Newer devices spurred the creation of a unique sampling tradition within music-makers at this time. Oswald explains how devices like tape recorders are documentation tools and creative instruments simultaneously allowing a blurring of the lines between theft and invention. The artist is the only authority, under the practice of plunderphonics, who can dictate which is which.

Watching these transformative shifts culminate in new rap genres, Oswald posits that, like the samples in hip-hop records, the music that follows plunderphonics is also valid. From his white Canadian perspective, an outsider looking in, music composed using samples and music composed solely of samples should be treated the same.

With the everpresent tunes of pop hits and jingles flowing through every mall, shop, and office corridor, music invades public spheres. If an artist is pulling inspiration from their surroundings, Oswald argues, would it not be completely legal and fair for their music to be wholly composed of stitched-together samples, if that is what they're hearing everyday?

Oswald’s Dilemma

As an experimental genre, plunderphonics reflects a maker market in the burgeoning musical sphere of the 1980s that is becoming larger and increasingly tech-savvy. Oswald makes fair and prescient claims considering he made his presentation in 1985. His tone, however, is the first indication of how deeper issues of theft, participation, and cultural inheritance are interwoven into the plunderphonics practice.

Laced with subtle antagonism, Oswald presents plundering as the right of anyone and everyone in the modern age; that all music is ripe for the taking. For him, overlaying “African pygmies” over Dick Hyman’s “Fabulous” with no editing, for example, is an execution of this thesis. 4 This turns the idea of liberation from the confining definition of what music ”is” into a question of liberation to do whatever with whatever, in order to make music. In the opening section of his essay, Oswald approvingly notes how hip hop artists can play "a record like an electronic washboard," transforming it into an instrument; likewise, the tape recorder transforms its captures into new productions. His parallel makes sense: he picks an established field to support the legitimacy of a new one. Oswald's genre-bending manifesto does not incite violence or call for the abuse of a particular group's sonic culture. However, it does artistically impact those same scratch artists he claims to support, and claims as support to characterize his own musical ideas.

Jazz, Sampling, and Black Musical Language

Non-white musicians in the United States had to suffer through segregated venues, style-stealers, and scalpers throughout their careers. Many of the protections and regards that were granted to their white counterparts were not provided for them. The history of sampling ironically starts in one of the most plundered immaterial landscapes of Black folks — jazz.

Jazz and the Beginning of Sampling

Jazz is a patently African-American genre which stems from the many thoughts and feelings of Black Americans living in and migrating out of the South.5 One of the first musical traditions to admit sampling, jazz artists would incorporate progressions and licks from their peers into their performances as a nod of admiration.6 These nods and improvisations have an established history stemming from gospel.

Someone who exemplifies the connection between jazz and gospel is Della Reese. Garnering her skills through church, community, and contests, her talent acquired her mass acclaim. Items like music folders for violinists, for example, are a testament to her prominence as not just a successful jazz artist, but an artist popular enough to perform with a full ensemble of talented musicians. It also serves as an example of the contrast between the beginnings of gospel and its contributions to the growth of Black jazz music. It is rare for Black churches to have violins, much less have them play a prominent role in gospel music to begin with. This is opposed to other gospel techniques that are carried strongly into jazz. The “call and response” motifs that were so prevalent in Black spiritual music, as well as the percussive elements, provided a strong foundation allowing many choir participants and blues singers, like Della Reese, to flourish in jazz. Black musical language adapted well to other genres that stemmed from the same African American roots. Call and response itself could even serve as a distant link to the “inside jokes” jazz artists were using. These nods became crowd-pleasers, and evolved into the jazz DNA throughout the 1920s and beyond.

What came from the Black community was a sense of togetherness that enabled jazz to be a highly synergistic experience between the band, the band leader, and the audience listening. This community feeling was important for artists at the time, set against the backdrop of a not-so-distant 19th century—whose abuses of Black musicians in fact carried into the 20th century’s jazz age.

Hope for Fairness, and Letdown

In this new post-Civil War era heralded by the recent abolition and delegitimization of nationwide slavery, Black artists held out hope for fairness. They were fed a tenuous promise of better treatment. They thought they had only just rounded the corner where their talents had been forcibly used to profit off of white curiosity.

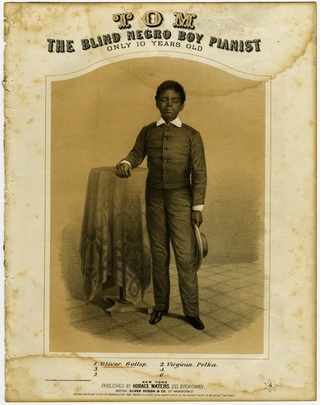

For instance, see the example of this ten-year old pianist. Although he was cherished and paraded for his remarkable talents, neither he nor his parents ever saw any form of currency and he was kept under the “guardianship” of his slaveholder’s family until his death. Here he is depicted around the start of his career as a child slave prodigy. The sheet music and he himself are a testament to the sort of figure Black artists wanted to avoid in the 20th century. Not only was his likeness used for the profit of his slave owners since childhood, but his productions never led him to an independent life. Tom, the Blind Negro Boy, thus functions as a cautionary and painful exhibit for Black musicians.

Horace Waters, Tom, The Blind Negro Boy Pianist, Only 10 Years Old, 1860s. Engraved sheet music, 5 pages. This is the second page. The front cover's title reads "TOM / The Blind Negro Boy Pianist / Only 10 Years Old"

Church Funding and Self-Help as Options for Black Musicians

In the late 19th century music was still a segregated front where Black artists battled for recognition. Artistic ventures and expressions were funded by and within the Black community. The Black church is often cited as a gateway for many in their introduction to singing and instrument playing, where the necessary pianos, trumpets, guitars, and the like were provided by parishioners.

Some of these donations did not go directly to a church, but to a religious leader’s foundation, like the ones given to Reverend Daniel J. Jenkins and his Jenkins Orphanage Band. Playing instruments donated by the very religious Charleston community, the boys in the band raised money to support their own care, as Jenkins felt unable to provide for the growing number of children under his tutelage.7

Multifaceted Abuse of Black Musicians, the Role of Unions, and White Pushback

Music recording companies were prepared to reap the benefits of contracted Black performers. However, they short-changed Black musicians repeatedly when it came time for the performers to reap the benefits of their own work. While audiences were absorbing, even relishing, this unprecedented sound, dancers, singers, and big bands suffered from withheld payments and suppressed acclaim.

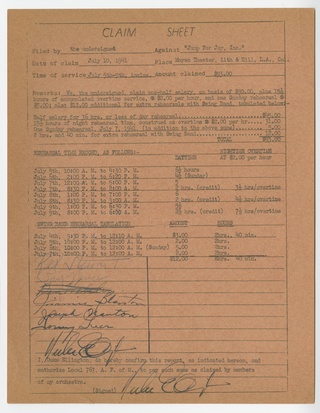

Black artists had to seek independent routes to lobby for themselves and argue for their worth. The Local 767 Music Union in Los Angeles is an example of a community center run by and for black musicians who were often victims of purposeful mismanagement and weaponized regulations. Opened by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), the Local 767 was an AFM branch that provided emotional support for Black performers, as well as legal aid.

A Los Angeles Local 767 Music Union claim sheet form was filed by musicians working under Duke Ellington’s “Jump for Joy, Inc.” when they were not paid. Duke Ellington also signed it. This provides an example not only of the measures prominent Black artists had to take to get paid, but also of how Black musicians maintained camaraderie, and organized and reinforced a sense of accountability, during a time where Black codes and Jim Crow laws maintained a palpable, pervasive form of oppression.

Unions could provide counsel for established ensembles, as well, who could use their input as a way to establish day rates, booking fees, and break times. Ensembles signed under agencies could then use the agency’s provided contracts as a way of firmly outlining their expectations, seen here with B.B. King’s contract for him and his orchestra with the Buffalo Booking Agency. However, note that the Agency itself did not sign the contract, thus leaving the door open for future exploitation.

Contract for B.B. King and Orchestra, Buffalo Booking Agency, contract dated August 18, 1955.

Despite being used for profit, Black Americans were still billed as the scapegoats for the moral, spiritual, and economic problems facing the country. This exploitation and villainization continued in the post-war United States, gaining in strength into the 1960s and 70s, even while Black musical arts evolved new branches in style and genre. Rather incredibly, lauded white jazz critics more often villainized the Black Americans who were involved in jazz as the real evil-doers who were bringing down the genre's reputation.8

Handbill from the Citizen's Council of Greater New Orleans, Inc., ca. 1965. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

This characterization of the nature of Black music as evil and unpolished increased in the high-tension environment of the Civil Rights era. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, handbills like the one pictured from the Citizens Council of Greater New Orleans called for white people to strike against Black records. This poster rabidly proclaims: “The screaming, idiotic words, and savage music of these records are undermining the morals of white youth.” These calls-to-action were indicative of the ways in which white America blamed Black music and musicians for ruining America’s social makeup.9

Again, non-white musicians in the United States had to suffer through segregated venues, style-stealers, and scalpers throughout their careers. Their white counterparts had protections provided to them, but few were extended to Black artists. Jazz, one of the most plundered immaterial landscapes of Black folks, positions itself in the midst of this strife and demoralizing rhetoric as a unique cultural sound to spawn even more significant styles within the Black community.

Community (Re-)Takings of a Special Black Sound

Despite being worked to exhaustion and witnessing constant theft of their contributions, Black artists held onto something sacred: their unequivocal cultural uniqueness, crafted and grown from the specificity of their homesteads and backgrounds. The differences in communities had generated an unparalleled, if often imitated, Black musical sound and sound language.10 Even with white vocalists pinching these stylings, even with suppression and mockery, what couldn't be taken was this profound je ne sais quoi, this special ours.

A Sonic Scramble

The special “ours” that constituted the Black musical sound extended sampling into newer genres, like hip-hop. Hip-hop’s musical ethos, however, made sampling a part of its DNA, its defining technique, whereas earlier it was a feature of jazz’s special sound practice. Sound experiments and tape looping were not odd characters in the landscape, but never before had a genre been so identifiable by its usage of preexisting media.11 The 1970s and 80s saw this technique boom with the advent of widely-available commercial synthesizers that improved upon sequencing technology. This led to the mastery of the breakbeat, which created magnificent energy bubbles.12

Technological Revolutions of Hip-Hop

Black artists face an overarching racist American culture in all aspects of their lives, not just in the dwindling opportunities for their own ventures. At a time in the 70s when this systemic racism was questioning the legitimacy of funding Black Americans’ public education, hip-hop offered an alternative to young artists.13 14 The creative backbone of hip-hop was not only present in the immense lyricism coming from youths participating in this burgeoning genre; the sound producers and engineers, the technicians that crafted these sounds from media they'd grown up on and were listening to, were equally critical.

Hip-hop was unique in creating a soundscape that echoed the environment of the cities and towns producers lived in, and used pop culture that was culturally specific to, and popular among, Black Americans: the sounds from the theaters where they watched their movies, the radios and turntables where they heard their parents' records. The mixing of new, attainable technology with years of available records to play with offered a bevy of opportunity. Once considered quite pricey, by the 1970s, synthesizers and MIDI sequencers had already established their professional credits among funk and synth-pop.

How Black artists coming to Hip-Hop utilized these technologies demonstrated a clear, new approach to creating a tapestry of sound and image. Sampling could string together the inspirations, lived environments, and occupied ecologies of Black Americans, by Black Americans. It was solid proof of existence. An existence that became available for sonic reinterpretation in the free market.

The Musical Free Market and Globalization

Oswald’s 1989 hit self-released giveaway album, Plunderphonics, was never meant for sale.15 The album's CDs were distributed freely to libraries, reviewers, and radio stations—but never with profit in mind. Before the Canadian Recording Industry (CRIA) demanded all remaining physical copies to be destroyed, it was Oswald's belief people could listen to it for free and record it on their own devices, continuing the plundering loop.16 Sound and music are not just themselves simple creations that follow a beat; the sonic nature of a people, of a place, could hardly be replicated through words before dissemination via recordings. Thus, sound as a cultural commodity cannot be owned and disputed very easily. When technological mastery is included as a tool in the creative’s belt, and that belt becomes easier for people to adopt, these intersections between freedom to listen and freedom to change grow en masse under globalization.

It isn't surprising that the (disputable) title holder for the first modern song to use a sample rips the "tribal rhythm made by 25 drummers of the Ingoma tribe in Burundi that originally appeared on the 1968 album, Musique du Burundi."17 18 Globalization has brought other sounds to the ears of people around the world. This exposure to different cultures, different vocalizations, instruments, didn’t stay exclusive to CDs and movie screens.

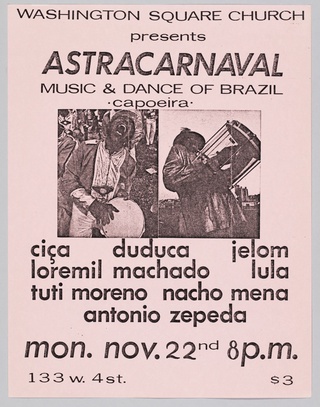

Groups like Astracarnaval would be advertised on fliers, as seen above, highlighting their display of, in their case, Brazilian song and dance. This exposure to different backgrounds through exhibitions and festivals was a tried and true method to attract new eyes. These exhibitions were also a product of a growing globalized society. Musicians have long since performed at open venues, advertising their ethnicity or background as a draw for curious audiences.19 Playbills and posters like these created a paper trail that could give credence to performers, too, and color diversity into varying cities as the Civil Rights movement picked up in the 50s and 60s. These exhibitions were not just sharing pop culture, but showcasing a cultural practice of beat and rhythm.

Potential for Missteps Despite Globalization

Music has traveled far and wide beyond the usual lines of migration. As musicians in each nation and culture are exposed to and influenced by external and internal popular influences, missteps are bound to happen. If the flurry of fury, pain, and nuance that Black music is steeped in is not acknowledged, if Black music is appropriated and stolen without its context intact, Black artists can find themselves locked out of the conversation. Showcasing cultural outputs expands the number of people who know about a practice, and by no means should sharing be discouraged — especially when emerging from a past where disenfranchised persons were made to feel shut out from cultural activities.

In this mid-19th century painting titled The Power of Music we witness the harmful effects of this sonic segregation, with the black laborer being shut out from a white-filled space. Hidden, the laborer smiles, although the sympathetic depiction only just scratches the surface of pain and abuse. Black fiddlers were lauded for their exemplary talent on the instrument shown here, a fiddle, with slaves playing at plantation balls and freemen up North on public streets. For the same cycle of ostracization, segregation, creation, and misappropriation to continue for well over a century signals the persistent and systematic ills that Black artists suffer.

Continued Role for Plunderphonics’ Ethos in Today’s Cultural Climate

Plunderphonics is still a vibrant genre, paired with the internet presence of vaporwave and future funk. What many say distinguishes it from other easy-listening niche genre types is how the samples lack much alteration at all. No screws are enabled and little is done with change of pitch, pace, or layered instrumentals in many records. "Appropriation," taking in what little handiwork is actually pulled off by the bigger names of this niche, feels somewhat light. Crafting work commenting on the beauty within the "crude, primitive, or outdated"20 holds so much potential that has essentially been whittled down to remastering easy listening works from a 2006 Chillout Ibiza CD.21

By transforming the, as Oswald says, “pygmy chants” into “sonic quotes,” a new type of innocent-seeming violence is enacted to a cultural product. Chants and drums are often used as a baseline or intriguing new note in a song composed of samples. Thankfully, these “plunderphones” don’t destroy the artifact of a people, but do mar significant meaning. And music is deeply meaningful. The Spaniards saw how meaningful and sacred music was to Indigenous Andean ceremonial practice, for example. So set were they on hastening Christian conversion in the region that they systematically destroyed thousands of musical instruments, like the rare surviving ceremonial drum pictured here.22 Major gaps in musical tradition therefore exist with items like the drum being incredibly rare, and a reminder of how music was targeted for its incredible weight in a society’s function and identity.

Conclusion: The Sonic Struggle

Wales has a story similar to the Andean drums being silenced by colonizers. With each invasion Wales suffered, pieces of its language were stripped. Their storytellers, cyfarwyddiaid, were rendered obsolete with the destruction of the basis of their existence—a royal court to sing tales about, to share stories of. Music is the production of a cultural body; arguably, without music, it can be difficult to define an assemblage of people as a culture. A community's sonic signature is essential to its identity—the weakness is obvious and exploitable.

If, then, a people is defined by the sound they create and evolve, what is it except stealing to not just appropriate that sound, but directly and blatantly use it with no chops, no screws, no loops?

Although recorded music is sold as CDs and streaming data, the sonic essence of a people is immaterial. Many cultures have had their sacred sound torn from them and, independent of their nation, chants and drums, scales and historical memories, undergo the disservice of being injected blatantly into a 120bpm Bandcamp single.

If plunderphonics is a revolutionary genre battling copyright, it is a genre that serves the typical audience who has benefited from "radicality" of this nature.

But if we are to repatriate important cultural items, how can we return a sound?

Reinterpretation and knowledge generation are beneficial pathways for other items, but may not apply to this nebulous field.23 Music is a sign of life—in folios and etched on instruments are reclamations of existences that would be forgotten. If it's possible to protect and gatekeep sonic totems in a technologically advanced age, should we? The diaspora has evolved the branching tree into something so large and neverending that maybe a song influenced by five different countries cannot be torn between those pairs of hands anymore. Culture has become a commodity; the free market of sound, as long as it can be afforded, unfortunately means anything is game to sell.

Brianna Beckford is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. Brie is a transdisciplinary artist working to curate stories and sites that only ghosts can make. Looking at old internet, archival efforts, and obsolete technology, Brie balances fun and discomfort through multiplatform installations to communicate this study. These real and imagined artefacts contribute to the ethnographic map linking diaspora babies, meme culture, and museums.

Suggested Readings

Citations

Hernández, Deborah Pacini. “‘La Lucha Sonora’: Dominican Popular Music in the Post-Trujillo Era.” Latin American Music Review / Revista de Música Latinoamericana, vol. 12, no. 2, 1991, pp. 105–23. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/780085. Accessed 21 July 2023.

Westerkamp, Hildegard. "Soundwalking." Sound Heritage, vol. 3, no. 4, 1974, pp. 18-27, www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writingsby/?post_id=13&title=soundwalking. Accessed 6 August 2023.

Oswald, John. "Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative." Plunderphonics,1985, www.plunderphonics.com/xhtml/xplunder.html. Accessed 21 July 2023.

Oswald, John. “Plunderphonics: a transcript of the plunderphonics EP sleeve and liner.” Album.notes, n.d., http://www.plunderphonics.com/xhtml/xnotes.html. Accessed 21 August 2023.

Carney, Court. "Jazz, Blues, and Ragtime in America, 1900–1945." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, 31 August 2016, Oxford University Press, doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.342. Accessed 5 August 2023.

Crilly, Aidan. “A Brief History of Sampling.” University Observer, 29 September 2017, universityobserver.ie/a-brief-history-of-sampling/. Accessed July 21 2023.

“Photograph Postcard of the Jenkins Orphanage Band, Charleston, South Carolina.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2014.63.88.1. Accessed 19 August 2023.

Anderson, Maureen. “The White Reception of Jazz in America.” African American Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 2004, pp. 135–45. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1512237. Accessed July 21 2023.

Stephens, Randall J. ”Race, Religion, and Rock ‘n’ Roll.” The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock ‘n’ Roll. Harvard University Press, 2018, pp. 65-101, doi.org/10.4159/9780674919747. Accessed 6 August 2023.

Leonard, Neil. “The Jazzman’s Verbal Usage.” Black American Literature Forum, vol. 20, no. 1/2, 1986, pp. 151–60. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/2904558. Accessed July 21 2023.

Sound collage and music experiments have existed as theory since the start of the 20th-century, and were put into motion notably in the 1940s under musique concrète.

Baruch, Yolanda. “DJ Kool Herc’s Sister Cindy Campbell Talks the Birth of Hip Hop Christie’s Auction.” Forbes, 11 August 2022, www.forbes.com/sites/yolandabaruch/2022/08/11/dj-kool-hercs-sister-cindy-campbell-talks-the-birth-of-hip-hop-christies-auction. Accessed July 21 2023.

Chalkbeat, Matt Barnum. “San Antonio V. Rodriguez: Does Money Matter in Education?” Vox, 22 February 2023, www.vox.com/the-highlight/23584874/public-school-funding-supreme-court. Accessed July 21 2023.

Alridge, Derrick P. “From Civil Rights to Hip Hop: Toward a Nexus of Ideas.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 90, no. 3, 2005, pp. 226–52. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20063999. Accessed 19 August 2023.

"Plunderphonics 69/96." Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plunderphonics_69/96&oldid=1118264806. Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

Oswald, John. “Plunderphonics - Negation.” Worldwide press release on 9 February 1990, Canadian press release 7 January 1990. Plunderphonics, www.plunderphonics.com/xhtml/xnegation.html. Accessed July 21 2023.

“Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative.”

Potter, Jordan. “What Was the First Song to Use Sampling?” Far Out Magazine, 7 July 2022, www.faroutmagazine.co.uk/the-first-song-to-use-sampling. Accessed July 21 2023.

Jordan, Jennie. “Festivalisation of cultural production: experimentation, spectacularisation and Immersion.” ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, pp. 44-55. Accessed 19 August 2023.

Alper, Max. “Pirates on the Sampling Seas: A Brief History of Plunderphonics.” Hii Magazine, June 28, 2022, www.hii-mag.com/article/pirates-on-the-sampling-seas-a-brief-history-of-plunderphonics. Accessed July 21 2023.

I love the 2006 Chillout Ibiza CD and am not critiquing easy listening so much as observing the tepid approach to critiquing pop culture with easy listening tracks that some plunderphonic practitioners utilize.

“Painted Drum.” Cleveland Museum of Art, 13 March 2023, www.clevelandart.org/art/2022.37. Accessed 19 August 2023.

Kendall Adams, Geraldine. “A New Approach to Repatriation.” Museum Association, 2 November 2020, www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/features/2020/11/a-new-approach-to-repatriation. Accessed July 21 2023.

Brianna Beckford is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. Brie is a transdisciplinary artist working to curate stories and sites that only ghosts can make. Looking at old internet, archival efforts, and obsolete technology, Brie balances fun and discomfort through multiplatform installations to communicate this study. These real and imagined artefacts contribute to the ethnographic map linking diaspora babies, meme culture, and museums.