Race and the Pop Culture Cowboy

By Reina Gattuso•January 2023•16 Minute Read

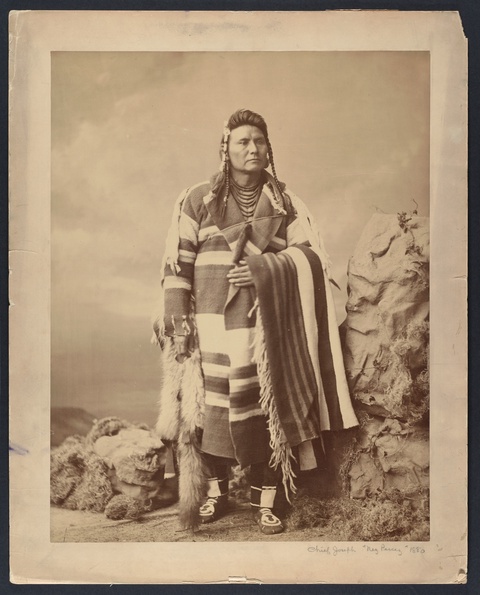

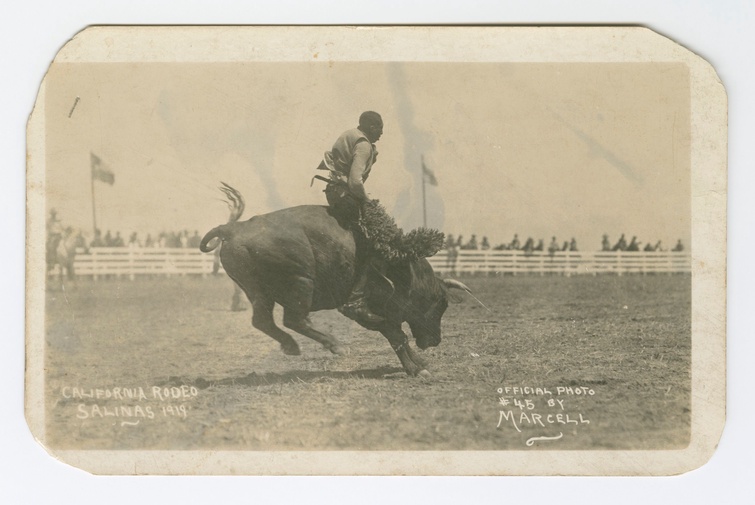

Unknown (United States), California Rodeo, Salinas, 1919. A cowboy rides a bucking bull in this picture postcard from the California Rodeo in Salinas while onlookers watch from behind a distant fence.

U.S. popular culture overwhelmingly depicts cowboys as rugged white men who embody the racist ideology of Manifest Destiny. In reality, many 19th and 20th-century cowhands were Black, Native American, and Mexican. Visual depictions of cowhands of color reveal the complex lives of marginalized people in the American West.

Introduction

The horse rears up, its arched neck straining as it attempts to throw an unwanted passenger. The cowboy looks athletic, capable, and unhassled; his hat hasn’t even been disturbed by the bucking horse. He raises his crop to strike.

This is the action of Frederic Remington’s 1895 sculpture The Bronco Buster. Remington was a New York-born artist who became famous for paintings and sculptures idealizing the so-called Wild West. The Bronco Buster exemplified many mainstream depictions of the American frontier. It shows a ruggedly masculine, white cowhand dominating nature, here represented by a feral horse.

To the settler-colonial imagination, “nature” included the land’s Indigenous stewards as well as its animals, plants, and terrain. U.S. imperialists used the white supremacist ideology of Manifest Destiny to justify colonization of what is now the American West. Proponents of Manifest Destiny argued that the Christian God had decreed Euro-Americans should rule what they called North America. They thus considered the displacement and genocide of Native peoples justified, even divinely ordained.1

As part of Euro-American colonization, cowhands or cowboys drove cattle across the terrain. White cowboys dominated perceptions of the Wild West in much of the 19th and 20th centuries. Popular culture depicted cowboys on postcards, in advertising, and in cinema. These images portrayed white cowboys as ideal settlers. They were often shown as macho guardians killing Native Americans and “saving” white women and property.

These popular depictions largely erase the fact that Native American cowhands and vaqueros, cowhands from Spanish colonies in what is now Mexico and the southwestern United States, actually preceded their white colleagues. Approximately 9,000 Black cowhands lived in the late 19th-century west.2 They were largely erased from popular depictions.

Scholar Durrell M. Callier argues that this erasure is part of Euro-American colonialism. “This imperial project necessitates and indeed perpetuates a cultural amnesia,” Callier writes, “disappearing the lives, stories, and histories of not only native and indigenous people but that of all other racial and ethnically marginalized peoples.”3

Despite this, some postcards, movie posters, and rodeo souvenirs did depict cowboys of color. These images were primarily visible in cinema and visual culture geared toward audiences of color. Black cowhands reappeared periodically, though infrequently, in mainstream late 20th-century films. They were often used as metaphors for injustice in society at large.4

Images of cowhands of color help us understand U.S. racial ideologies in the 19th and early 20th centuries. These depictions both perpetuated and challenged settler-colonial ideology, revealing the complexity of marginalized people’s lives in the American West.

Cowhands of Color in the American West

Spanish colonizers introduced cattle to the American continent, where they formed feral herds.5 Cattle ranching thrived beginning in the 1500s in what is now Mexico. Cattle devastated Indigenous agricultural land.6

Vaqueros herded these cattle. They could be of any combination of Indigenous, Spanish, and African ancestry.7 A sculpture cast in 1990 by Mexican-American sculptor Luis Jiménez riffs on Remington’s sculpture of the cowboy. In the white cowboy’s stead, Jiménez portrays a brown-skinned vaquero.

Greyloch, Photo of Luis Jiménez’s Vaquero, 2012. Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0. Luis Jiménez’s sculpture of a vaquero shooting a gun atop a bucking horse adorns Washington DC’s Smithsonian Institute.

Ranching became a large industry in the United States in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, cowhands drove herds of cattle from Western ranches to nascent railroads in places like Kansas and Missouri. From there, they were shipped to stockyards back east.8

Historians estimate that around a quarter of cowhands in the U.S. were Black. Many African people brought ancestral knowledge of cattle with them to the Americas when Europeans enslaved them.9 Enslaved people were made to tend their enslavers’ cattle. After Emancipation in 1863, many African Americans migrated westward.

Indeed, the word “cowboy” has racist origins. White cattle workers were called cowhands. In contrast, bosses referred to Black cattle workers as cowboys, using “boy” as a racist diminutive. The term cowboy later came to stand for the trade as a whole. Ironically, the term was then whitewashed to exclude Black cowhands from the public imagination.10

Photography and the West

The heyday of the cowboy coincided with the advent of photography. Studio photography and the rise of inexpensive printing technology facilitated a dynamic visual culture.11 Many portraits of cowhands exist in the form of postcards and cartes de visite, small studio prints that people would often exchange.

The Settler Gaze

In the 19th century, colonial regimes in the United States and the British empire used photography to document the people they attempted to rule. In doing so, they staged race as a visual and scientific category.12

Settler photographers, most notably Edward Curtis in his vast portfolio The North American Indian, tended to depict Indigenous people as a “vanishing race.”13 Photographers staged Native people as though “captured in their ‘native wilds’ or posed in photographers’ studios with props that would ensure their ‘Otherness,’” writes curator Cécile R. Ganteaume.14

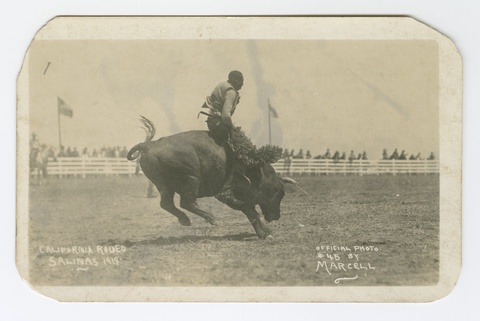

Consider a photograph of Hinmatóowyalahtq’it, also known as Chief Joseph. Hinmatóowyalahtq’it was a Wal-lam-wat-kain Nez Perce leader who resisted the white occupation of his homeland in what is now Oregon. The United States government incarcerated him and other Nez Perce people on a reservation in what is now Oklahoma. In 1879, the government permitted him to travel to Washington, D.C. as part of a delegation to the president. There, Charles Milton Bell took his portrait. In the photograph, Hinmatóowyalahtq’it poses against a studio background of painted sky and paper mache boulders.15

Bell cast Hinmatóowyalahtq’it in an imaginary American West, using the same props in his photographs of several different Native leaders. This settler staging of a generic landscape recalls Hinmatóowyalahtq’it’s confinement far from his ancestral lands. Bell’s portraits are often read as portraying “types rather than individuals,” yet they are also records of Native leaders’ advocacy for their communities, write artist Wendy Red Star and Met curator Shannon Vittoria.16 The photograph of Hinmatóowyalahtq’it is thus both a reinscription of ethnographic violence and a record of a visiting dignitary.

Indigenous American photographers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Richard Throssel, Jennie Ross Cobb, and Horace Poolaw, challenged the visual coding of Native people as remnants of a bygone age. They depicted Native Americans as active participants in the complexities of modernity. In the early 21st century, Native photographers continue to reimagine the ethnographic project of documenting Native Americans, with works such as Diné photographer Will Wilson’s Critical Indigenous Picture Exchange and Swinomish and Tulalip photographer Matika Wilbur’s Project 562.17

Photographing the Cowhand

Like studio photographs of Native Americans, many pictures placed cowboys within an idealization of the western landscape. While Native Americans were often staged as solemn representatives of a vanishing premodernity, cowhands—including cowhands of color—tended to be depicted as bold working men, agents of the world to come.

In one carte de visite, a vaquero stands against a painted desert. The Smithsonian museum that holds the image doesn’t offer information on how the vaquero came to have his photograph made, but we can imagine the vaquero dressing up for the occasion.

Photographers in the west also documented Black cowhands in studio portraits and rodeo postcards. Scholar Bryant Keith Alexander writes that, in such photos, Black cowboys are “staged not unlike their filmic white counterparts with stylistic garb but maybe with slightly different intentions; not fashion; not staged with desirous intent,” he writes. Instead, they are “working Black cowboys.”18

Unknown, Nat "Deadwood Dick" Love, 1907. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions on publication.

Some photographs illustrated famous Black cowboys, as in this image of Nat “Deadwood Dick” Love from the cowhand’s immensely popular autobiography. The photograph is captioned “in my fighting clothes.” Love’s frontal pose communicates a sense of defiant, masculine pride in line with the tall tales that fill his book.19

Other images included less well-known but equally striking Black cowhands. A postcard from the early 1900s features a tightly framed studio image of a Black cowhand. He meets the viewer head on, hands on hips, hat brim tipped upward—perhaps aspiring to the punchy aesthetic of famous figures like Love.

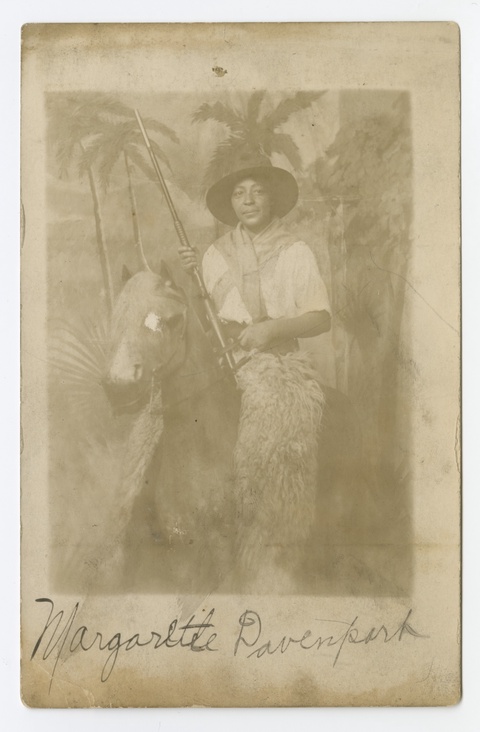

Cowhand culture inspired imitation in novelty studio photographs among members of the general public, including Black sitters. In one early 20th-century image, perhaps a souvenir, a woman in a cowboy hat and gun sits astride a fake horse against a studio backdrop of palm trees.

Postcards also showed Black cowboys in action. One postcard shows a Black contestant riding a bull at the California Rodeo. The Salinas event included some Black riders in the 1910s, when this photograph was taken.20 Black riders also formed their own rodeos, since many shows excluded riders of color.21

To Alexander, photographs of Black cowhands offer the contemporary viewer “a moment of accountability and remembrance; a moment of presencing and validation” of Black community in the American west.22

Cowboy Shows and Westerns

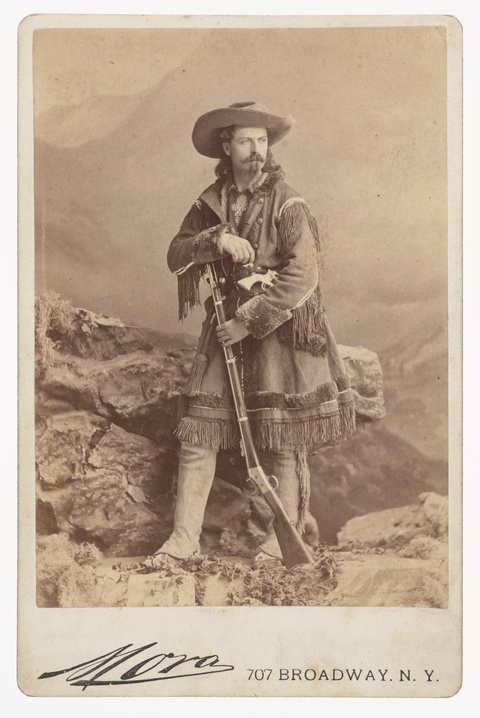

Wild West shows combined displays of cultural difference with the daring feats of the circus. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, a white male erstwhile buffalo hunter, pioneered the form. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show included demonstrations of ranch skills and reenactments of famous historical battles. Indigenous people performed dances for largely white audiences in various Wild West shows. Buffalo Bill’s shows toured the United States and Europe over several decades.23

New York-based photographer José María Mora shot a studio portrait of Buffalo Bill in 1875. The showman wears a long fringed coat and cowboy hat and leans against a rifle. Yet this, too, is a costume: Bill is silhouetted not by distant mountains but by a set in New York City.

Some Native people criticized Wild West shows in their heyday as portraying racist ideologies. “We see that the showman is manufacturing the Indian plays intended to amuse and instruct young children and is teaching them that the Indian is only a savage being,” wrote Chauncey Yellow Robe, a Sičáŋǧu Oyáte Lakota activist and educator.24

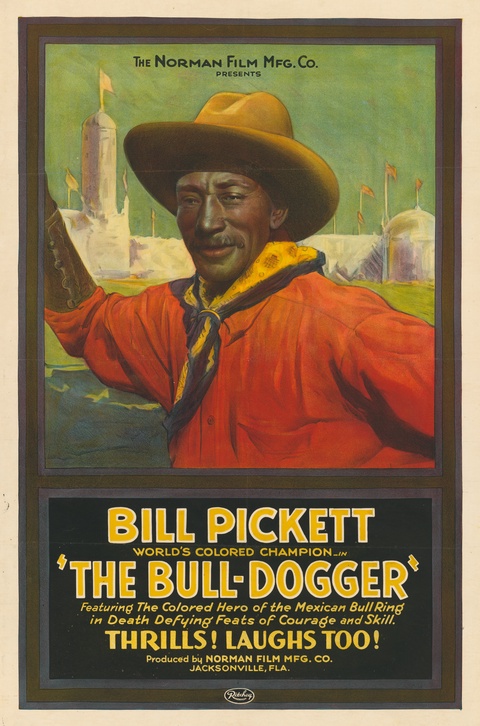

Yet many cowhands of color, as well as Native performers, used Wild West shows to earn a living and even gain fame.25 Indeed, Black cowhands pioneered some of the celebrated rodeo feats these shows were known for. Cowhand Bill Pickett invented “bulldogging,” a method of wrestling a steer to the ground with his bare hands. By the 1910s, Pickett was an international star. He performed in Wild West shows across the United States and in front of the Queen of England, as well as on film.26 Posters portrayed Pickett as a seasoned, confident cowhand of color.

Cowboy films became popular starting in the 1920s. Most of these films featured white casts. In the 1930s, however, producers released a series of cowboy films with all-Black casts. These films included Harlem on the Prairie and The Bronze Buckaroo. By bringing “Harlem” and “Prairie” together, the film’s title invited viewers to reimagine the west as a Black space.27 The Bronze Buckaroo was a “race film,” an early-cinema American genre that featured mostly or entirely Black casts. While some of the white-produced race films portrayed racist caricatures, many Black- and some white-produced films challenged stereotypes and paved the way for future Black filmmakers.28

The Harlem films starred actor and singer Herbert Jeffries. His racially ambiguous appearance was part of his celebrity. Jeffries had a white mother and a father whom he variously said was Black, mixed race, Ethiopian, or even Sicilian.29 He told a Life magazine journalist that he publicly affirmed his identity as a Black performer in order to increase Black representation in pop culture.30 It’s also possible that the fictional West, as a place of imagined lawlessness, granted Jeffries the space to play with racial categorization.

Reimagining the West

When he appeared as a queer cowboy in his 2019 song “Old Town Road,” pop star Lil Nas X made waves. The song soared to the top of country music charts. But Billboard Magazine compilers removed it from their list, claiming it didn’t “embrace enough elements of today’s country music.”31 Critics argued this reflected racism against Black artists within the country music industry. They pointed out that, despite the whitewashing of the genre, Black people were as fundamental to the creation of country music as they were to cowboy culture more broadly.32

Lil Nas X’s proud entry into country music is part of a broader public reclamation of U.S. Western culture by Black Americans. In 2018, archivist Bri Malandro dubbed this the “Yeehaw Agenda.”33 Images of Black cowboys took on a renewed political significance during the 2020 Black-led uprisings following the police murder of George Floyd. Groups like the Compton Cowboys protested racism while educating the public about Black cowboy culture. Contemporary artist Otis Kwame Quaicoe painted a series of portraits of Black cowhands. Quaicoe’s solo exhibition, “Black Rodeo,” opened in Brussels in 2022. Unlike the Wild West displays that had previously toured Europe, however, Quaicoe’s exhibition centered Black expressions of cowhand culture.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

Cox, Alicia. “Settler Colonialism.” Oxford Bibliographies, 26 July 2017, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0029.xml. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Glasrud, Bruce A. and Michael N. Searles. Black Cowboys in the American West, University of Oklahoma Press, 2016. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Black_Cowboys_in_the_American_West/glcdDQAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Callier, Durrell M. “But Where Were They? Race, Era(c)sure, and the Imaginary American West.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 12, issue 6, 1 December 2012. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708612457637. Accessed 29 August 2022.

Alemoru, Kemi. “How the Black Cowboy Figure Became a Cultural Phenomenon.” Mr. Porter, 5 November 2021, https://www.mrporter.com/en-it/journal/lifestyle/the-harder-they-fall-black-cowboys-netflix-10139040. Accessed 21 July 2022.

McTavish, Emily Jane et al. “New World Cattle Show Ancestry From Multiple Independent Domestication Events.” PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1303367110. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Howell, Kenneth W. “Ranching Heritage.” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ha.034. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Patton, Tracy Owens and Sally M. Schedlock. “Let’s Go, Let’s Show, Let’s Rodeo: African Americans and the History of Rodeo.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 96, no. 4, fall 2011, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.5323/jafriamerhist.96.4.0503?journalCode=jaah. Accessed 7 June 2022.

“Cattle Drives in the United States.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cattle_drives_in_the_United_States. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Sluyter, Andrew. “How Africans and their Descendants Participated in Establishing Open-Range Cattle Ranching in the Americas.” Environment and History, vol. 21, no. 1, February 2015, pp. 77-101, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43299718. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Toussaint-Strauss, Josh et. al. “Why the First US Cowboys Were Black.” The Guardian, 29 October 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/video/2020/oct/29/why-the-first-us-cowboys-were-black. Accessed 7 June 2022. See also: Nodjimbadem, Katie. “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys.” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 February 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lesser-known-history-african-american-cowboys-180962144/. Accessed 7 June 2022.

“The 19th Century: The Invention of Photography.” National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/features/in-light-of-the-past/the-19th-century-the-invention-of-photography.html. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Halpern, Rick. “Photography and the New American Empire.” Frames, 28 April 2021, https://readframes.com/photography-and-the-new-american-empire-by-rick-halpern/. Accessed 7 June 2022. See also: Willmott, Cory. “The Lens of Science: Anthropometric Photography and the Chippewa, 1890-1920.” Visual Anthropology, vol. 18, no. 4, 2005, pp. 309-337. Taylor and Francis, https://doi.org/10.1080/08949460590958374. Accessed 29 August 2022.

“Contemporary Native Photographers and the Edward Curtis Legacy.” Portland Art Museum, 2016, https://portlandartmuseum.org/exhibitions/contemporary-native-photographers/. Accessed 29 August 2022.

Ganteaume, Cécile R. “‘Developing Stories: Native Photographers in the Field’ Presents Contemporary Native Experiences from the Inside.” Smithsonian Magazine, 24 March 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/author/cecile-r-ganteaume/. Accessed 24 August 2022.

“Hinmatóowyalahtq’it (Chief Joseph).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286068. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Red Star, Wendy and Shannon Vittoria. “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC: A Case Study in Re-Reading Nineteenth-Century Delegation Photography.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, vol. 6, no. 2, fall 2020, https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10672. Accessed 31 August 2022.

“Staging the Indian: The Politics of Representation.” Tang Teaching Museum, 2022, https://tang.skidmore.edu/exhibitions/188-staging-the-indian-the-politics-of-representation. Accessed 26 August 2022. See also: Estrin, James. “Native American Photographers Unite to Challenge Inaccurate Narratives.” The New York Times, 1 May 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/01/lens/native-american-photographers-unite-to-challenge-inaccurate-narratives.html. Accessed 26 August 2022; “Developing Stories: Native American Photographers in the Field.” National Museum of the American Indian, https://americanindian.si.edu/developingstories/index.html. Accessed 29 August 2022; Indigenous Photograph, https://indigenousphotograph.com/about. Accessed 29 August 2022.

Bryant, Keith Alexander. “Writing/Righting Images of the West: A Brief Auto/Historiography of the Black Cowboy (Or “ I Want to Be a (Black) Cowboy” . . . Still).” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1 June 2014. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708614527554. Accessed 29 August 2022.

Dodge, Georgina. “Claiming Narrative, Disclaiming Race: Negotiating Black Masculinity in ‘The Life and Adventures of Nat Love.’” a/b: Auto/Biography studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 2001, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08989575.2001.10815261?journalCode=raut20. Accessed 30 August 2022.

“History.” California Rodeo Salinas, https://www.carodeo.com/p/about-us/history. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Patton and Schedlock.

Bryant.

McNenly, Linda Scarangella. Native Performers in Wild West Shows, 2012. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Native_Performers_in_Wild_West_Shows/PpU9yueN5TwC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=wild+west+shows&pg=PP2&printsec=frontcover. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Yellow Robe, Chauncey. “The Menace of the Wild West Shows.” Quarterly Journal 2 (1914), pp. 224-5, 294-9, reprinted in Frederick E. Hoxie, ed., Talking Back to Civilization: Indian Voices from the Progressive Era, 2001, http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter8/QuarterlyJournal1914.pdf. Accessed 24 August 2022.

McNenly.

“Bill Pickett.” Smithsonian, https://www.si.edu/object/bill-pickett:npg_NPG.84.113. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Gott, Benjamin. "The Curious Case of 'The Bronze Buckaroo': Race and National Identity in the 'Singing Cowboy' Westerns of Herb Jeffries." Southwestern American Literature, vol. 40, no. 1, fall 2014. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A405925309/AONE?u=nysl_oweb&sid=googleScholar&xid=9c26b9c. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Butters, Gerald R. “Capitalizing on Race.” Early Race Filmmaking in America, 2016. Taylor and Francis, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315692753-7/capitalizing-race-gerald-butters. Accessed 8 November 2022.

Yardley, William. “Herb Jeffries, ‘Bronze Buckaroo’ of Song and Screen, Dies at 100 (or So).” The New York Times, 26 March 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/27/arts/music/herb-jeffries-singing-star-of-black-cowboy-films-dies-at-100.html. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Williams, Richard L. “He Wouldn’t Cross the Line: Herb Jeffries Cheerfully Pays the Price of Choosing His Race.” Life, 3 September 1951. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=k04EAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Mysers, Owen. “Fight for Your Right to Yeehaw.” The Guardian, 27 April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/apr/27/fight-for-your-right-to-yeehaw-lil-nas-x-and-countrys-race-problem. Accessed 24 August 2022.

Nittle, Nadra. “Lil Nas X Isn’t an Anomaly — Black People Have Always Been Part of Country Music.” Vox, 5 June 2019, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/6/5/18653880/lil-nas-x-country-music-billboard-wrangler-old-town-road. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Marine, Brooke. “The Yeehaw Agenda Explained: Why the Black Cowboy Is Suddenly Back in Fashion.” W, 14 April 2019, https://www.wmagazine.com/story/yeehaw-agenda-explained-black-cowboy. Accessed 25 August 2022.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.