How Bazaars Shaped Trade in Islamic Cities Before 1900

By Abbad Diraneyya•August 2023•18 Minute Read

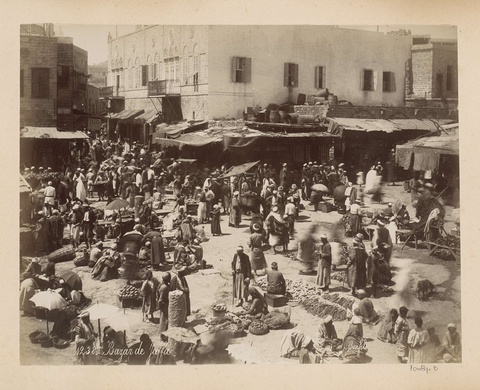

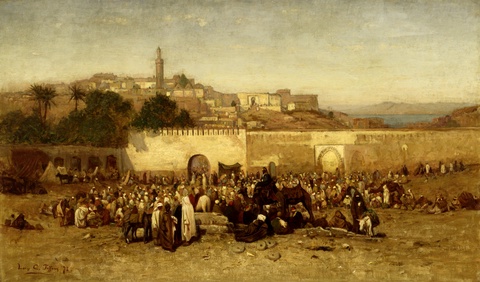

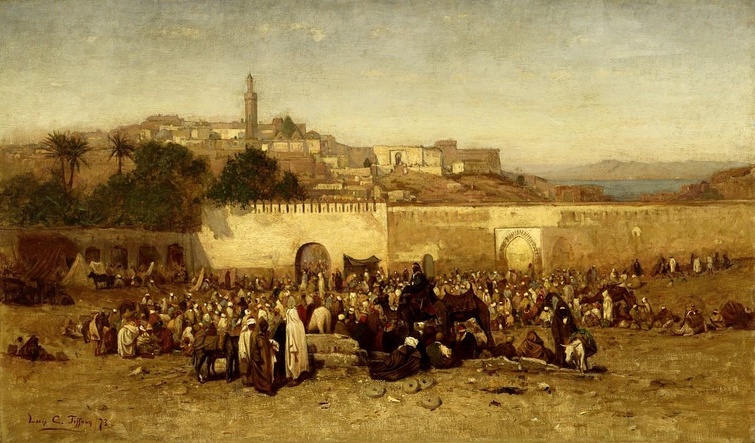

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Market Day Outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco, 1873. Oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, CC0.

Bazaars are considered a hallmark of urban Islamic culture. By exploring what they looked like 150 years ago, we can imagine how people used to live, trade, and socialize in many communities before industrialization transformed their ways of life.

Bazaars were once the economic and cultural cores of Islamic cities. They were usually the busiest spaces, attracting not only shoppers, but also curious visitors, musicians, poets, and other crowds from the city and beyond. Bazaars could be permanent markets or informal and temporary, whether seasonal, weekly, or occasional. They were held at neighborhood crossroads within the city and on roadsides in the suburbs or rural areas, attracting traders from miles away.1 2 3 While many Islamic cities, if not most of them, still appear to have busy bazaars today, a closer look into their past reveals that behind their attractive facade there is little of their old life left intact. The purpose, function, and influence of the bazaar has drastically shifted, repurposing itself to imitate what modern visitors imagine it once was. This can be seen through the lens of pictures, paintings, and travel accounts by bazaar visitors during the late 19th to the early 20th century.

The Bazaar or Souk

Bazaars are synonymous with souks, the term used to describe them in many Arabic-speaking countries.4 According to orientalist travelers, bazaars were a defining feature of cities in the Islamic world. These marketplaces were second only to mosques in setting apart the cities of “the East” from the hometowns of those European travelers.5 The bazaars were largely situated in the same place as the central mosque.6 What is it that sets those Islamic bazaars apart from markets that are depicted in the photographs, paintings, and written accounts left behind by the orientalist travelers from the West?

Part of the answer may be in the complexity of the bazaar’s origins. The word itself comes from the Persian language.7 This perhaps links the origin of bazaars to those markets in the ancient cities of Persia. Such markets existed as early as 2000 BCE in Mesopotamia, where some cities had streets dedicated to crafts like coppersmithing.8 The practice was transferred to Arabia after Islamic conquest,9 and then spread to lands as far as Spain,10 Bosnia,11 Turkey, and India.12

Bazaars thus evolved as an intercultural melting pot of diverse people from far and wide across the Islamic world and even beyond, including Moors, Arabs, Turks, Greeks, Persians, Jews, and Indians.13 The famous portrayal of peasants and bedouins at Egyptian bazaars by Leopold Müller captures this diversity in great detail, including every facial expression of people from all castes and races.

Leopold Carl Müller, Market in Cairo, 1878. Museum Belvedere in Vienna, public domain. A close-up and lively portrayal of an open-air bazaar in Cairo. Unlike many other paintings, it depicts a complex space of social interaction with detailed expressions, castes, and races, rather than a zoomed out “oriental” scene.

For the natives of cities with bazaars and souks, though, these seem to have been regular marketplaces. Arab travelers, when documenting the cities they visit, almost never used the word bazaar. Why would the different kinds of markets throughout a significant part of the world all be perceived under a single umbrella term? What characterized bazaars across this vast geography until the early 20th century? To answer these questions, it may help to first understand the goal of those markets.

From Trade to Recreation: Purposes of the Bazaars

Bazaars were normally at the center of Islamic cities, next to Al-Masjid Al-Jami’, as the main mosque in the city was called. During her 1918 visit to Marrakech, Edith Wharton observed that it was difficult to even approach merchants to talk with them or inspect their goods, due to the massive crowds in the narrow bazaar’s streets.14 In 1907, Gertrude Bell thought the entire city of Antioch to be almost deserted, until she found that it suddenly came to life when one approached the main bazaar.15 Such crowds of natives must have been attracted by bazaars for a reason. When people of such cities walked into a bazaar, what were they looking for?

Oriental Literature and Fantasy

In the early 18th century, a collection of Middle Eastern tales, One Thousand and One Nights, colloquially known as the Arabian Nights, were translated into European languages.16 Since then, an exotic image of “the Orient” has grown in European minds.17 These stories were sufficiently significant to encourage a new genre of “the Oriental tale,” which emphasizes unfamiliar customs and cultures.18 In James Joyce’s famous short story, “Araby,” the main setting is an oriental bazaar that the protagonist is initially fascinated with, although his idealized vision of the place is ruined upon actually visiting.19

Unlike Joyce, Mark Twain, a beloved American novelist and traveling journalist, finds that his exotic expectations are well-satisfied when he visits Tangiers, Morocco, in 1869. For him, it’s a “foreign land if ever there was one,” the spirit of which “can never be found in any book save The Arabian Nights,” about which fantastic tales and artworks “have not told half the story.”20 His writing led to a wave of interest towards the Orient in the United States, inspiring the artist Louis Comfort Tiffany to visit the same city in 1870-71. Tiffany was fascinated with what he saw, drawing this lively portrayal of a market outside the city walls, and accurately capturing elements of Islamic architecture that became a core part of his artistic style.21

Basic Necessities

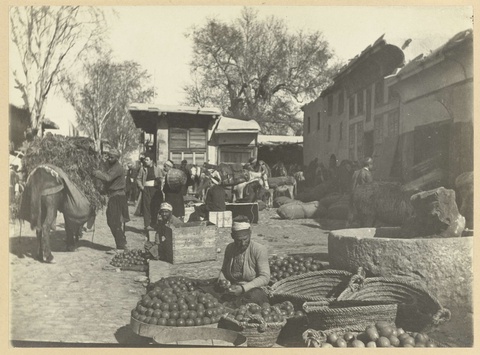

Despite their often enchanting architecture and atmosphere, most bazaars had a basic purpose. Each town had its own small bazaar, which were meant for locals simply buying necessities rather than those seeking curiosities. An American visitor to Acre, Palestine, in 1848 was frustrated to find the city’s bazaar exclusively offering “common necessaries of life.”22 Even in Cairo, one of the largest Islamic cities, the main content of the markets was reportedly “innumerable vendors [selling] all sorts of eatables.”23 In Tehran’s bazaar, the morning routine of local men would be gathering around sizzling kebab stands, waiting for their roasting breakfast. In the afternoon, housewives, completely veiled from head to foot, would roam between shops haggling for the ingredients of their family’s dinner.24 While such bazaars may have been disappointing to dreamy orientalists, they ably served the daily needs of city inhabitants.

Social and Religious Convenings

While bazaars may have originated as venues of trade, they were also frequented for entertainment. In Damascus, the largest crowds were not around the shops and their exotic goods, but in the surrounding cafes.25 Such cafes were (and still are) social spaces where people would sit for hours smoking nargile, chit-chatting with friends, and enjoying a refreshing drink.26 Some other bazaars attract crowds for more indulgent recreation. In Tunis and Algeria, “dancing-girls [with] brilliant dresses enliven certain streets.”27

Emile Bechard, No. 62, Café arabe, 1870s. Albumen print, Digitala Library of the Middle East, public domain. This photo of a traditional cafe in Cairo in the 19th century shows nargiles, coffee being served, and a varied group of customers.

Purposes of frequenting bazaars could even be religious, either directly or indirectly. It was usual for bazaars to emerge or converge around mosques.28 29 This led to a close association between the religious and economic centers of the city, joining both in a single hyperactive hub. Crowds flowed from the bazaars to mosques and vice versa. Merchants would even gather outside the mosques to sell and auction goods of all kinds, such as food or clothing, especially after Friday’s prayer.30

Léon Belly, Pilgrims Going to Mecca, 1861. Oil on canvas, Musée D’Orsay, public domain. Pilgrims caravans to Mecca played a major role in trade. Cities on the road to Mecca had bazaars specialized to cater for the pilgrims’ needs, and even bedouins on the road often traded with the caravan.

Across North Africa and Hijaz (now Western Saudi Arabia), many bazaars were chiefly dedicated to serving hajjis or Muslim pilgrims. Tripoli, Libya, was the last major stop for many pilgrim caravans before crossing a vast, desolate desert. They would stop there for weeks, procuring all sorts of food, animals, and supplies for the road. Pilgrims would even purchase specific goods for the purpose of bartering them with bedouins along the way,31 who wouldn’t accept any kind of money for the meat, milk, vegetables, and fruit that pilgrims required.32

Desperation and Ruin

For those unhoused or without means, the bazaar was a place of refuge. Beggars were a typical sight associated with many of the largest bazaars, including Constantinople33 and El-Kairouiyin.34 They seem to be as much of a fixture of the marketplace as its shoppers and vendors. This shows that the bazaar, as a social space, had a specific purpose even to the most marginalized castes and at the harshest of times. A more extreme example is the case of Kannauj’s bazaar, which became the center of begging for the unfortunate population suffering during a mid 19th century famine in northern India.35

The seemingly dark corner of a bazaar in Damascus puts us in mind of all this, but also depicts the bazaar in a state of emptiness. In place of the crowds, the space is sparsely populated with a bored shopkeeper, a limping old man, a mule with no goods to carry, desperate beggars, and stray or even dead dogs. While some of those elements are reported in various travel accounts, they seem to be excessively combined into a single unsettling sketch, replacing the lively bazaar with that of ruin and laziness of labor.36

This is a theme that was often associated with imperialism, as seen in the depiction of the poultry seller at rest. The fact that some painters reflected on bazaars in this way portrays, by itself, the importance of how they are depicted and portrayed in the public imagination.37

The Uniqueness of a Bazaar

What made the bazaar unique, therefore, is the sum of its contextual economic, social, and cultural purposes. It was not only a market in the practical sense, but a central meeting point for people in the city. As permanent marketplaces, souks were at the center of the city, surrounded by all essential facilities that meet people's needs, including mosques, cafes, caravanserais, madrasas (schools), hammams (baths), hospitals, restaurants and drinking fountains.38 Outside the city gates, fruit and grocery bazaars were often erected to serve people moving to the residential or rural areas.39 In deserts and desolate lands, bazaars were adapted to be more temporary or informal, catering to the regional population or travelers on the road.

Unknown Artist, Tunis Bab Souika, 1899. United States Library of Congress, public domain. This color lithograph depicts Bazaar of Bab Souika, next to Sidi Mahrez Mosque in Tunis, in 1899.

The diverse purposes of the bazaars, however, all came under threat at the beginning of the 20th century. The changing times inaugurated by industrialization brought direct competition to all the unique purposes that bazaars fulfilled, and transformed the experience and culture of bazaars in the region.40

Trade of Times Past: The Experience of a 19th-Century Bazaar

Bazaars of different sizes and shapes were located across a vast region stretching from Morocco to India. How different were the goods traded in different cities? If you went into one of those bazaars in the 19th century, what could you expect to see?

Unknown Artist, Burra Bazaar, Calcutta, c. 1880. Public domain. This Calcutta bazaar is significantly different from the typical MENA bazaar, with a wide open-air street full of carriages in place of the usual covered, damp and ill-lit narrow alleys. Shopping streets like this predate another form of markets that the British introduced to Colonial India starting from the 19th century, during which many confined market halls were built.

Bazaars were a place to buy almost anything. There would be all sorts of food: from meat to sweets, as well as grains, vegetables, and fruit like figs, dates, melons, and apricots.41 Silk textiles were quite common, much more than perhaps any other fabric.42 There were shops for clothing, shoes, skins, pottery, and weapons imported from many places. Large bazaars had silver- and goldsmiths.43 Interested buyers would be invited to sit down and have a coffee while inspecting goods.44

Many bazaars gained fame for their specialties. The bazaar in Salé, Morocco was known for its “exquisite mattings,” which were more plentiful than any other products in the city’s markets.45 Not far away, the souks in Fez were frequented for their embroidered saddlery, and Souss had special locally-made daggers.46 Al-Jawf in Saudi Arabia had special abayas, as well as swords with gold and silver-embroidered sheaths.47 Kabul bazaars held a reputation for “endless quantities of delicious fruit and flowers.”48

Some bazaars were almost unbelievably lavish, with all the luxuries and “gaudy trifles” of modern life.49

Emanuel Stöckler, Constantinople: The Great Bazaar, 1849. The Royal Collection Trust, public domain. The Grand Bazaar in Constantinople was one the largest and most diverse bazaars in the world. A visitor would be easily lost without guidance.

Constantinople’s grand bazaar was a chief example. It was one of the largest bazaars in the world, described as a “labyrinth of narrow streets” where an unguided visitor readily loses their way.50 Each street was usually dedicated to a specific kind of goods or crafts, the diversity of which was “beyond description.”51 One pilgrim, on his way from Morocco to Mecca, recounts with bewilderment how markets in Constantinople’s bazaar were dedicated to articles ranging from seasonal fruits that are available all year-round52 to an insect market with many varieties used in making medicine, and even an entire market just for ear picks.53

Tides of Change in the 20th Century

The core function of bazaars came under severe competition with the rise of industrial production and modernization in the 19th century.54 Markets that were once the central destination for commerce had to be redistributed to new areas due to booming urban populations.55 Items which people could only buy at a bazaar, such as eggs, fish, meat, and other food products, became increasingly available in supermarkets.56 The winds of change quickly transformed the economic and spatial organization so central to bazaar-based cities.

Mass-produced European goods started invading bazaars as early as the 1850s.57 These commodities were in markets as far away as those of Fez,58 Damascus,59 and even the desert markets of Eastern Arabia. They included factory made fabrics and clothing that Europeans themselves thought “only Orientals admire,”60 as well as canned foodstuffs like sardines and corned beef.61

This mass production introduced fierce competition to the local and regional products that bazaars chiefly traded in.62 Buying foreign goods also directed a lot of income to outside the region. A typical colonial economy emerged, where the colonized states would export raw materials and import finished goods. In a prominent example, British products dominated Indian markets by the end of the 19th century, offered at a much cheaper price compared to local products of similar quality.63 British exports to India, which grew steadily,64 included numerous amounts of cotton yarn, iron and steel,65 and cutlery.66 By the 20th century, the flood of Chinese manufactured goods gradually bankrupted local and traditional crafts, forcing some bazaars to become mere outlets for imported products.67

Unknown Artist, The Imperial Fez Factory which has been recently built, 1880. Library of Congress, public domain. This image shows the early competition in Fez, Morocco to the traditional craftsmanship of bazaars that eventually led to their dramatic transformation.

The most deciding factor in shifting the role of bazaars was the introduction of department stores, retail chains,68 and, later, shopping malls.69 Unlike the bazaar, those new structures had a solely commercial purpose.70 Such modern shopping districts revolutionized the consumer’s experience, reframing shopping, once simply a necessity, as a pleasure.71 The modern, spacious, and air-conditioned stores were too enticing in comparison to the old, narrow, and noisy streets.72 They quickly drew the crowds away from the old-fashioned marketplaces of major cities like Cairo and Isfahan. Not only the economic role of the bazaar, but even its social function declined as the new generation turned away from it. Many bazaars suffered,73 but they also didn’t disappear entirely.

Resilience of Bazaars, Transformed by Fantasy

Unknown Artist, Qatif Khamees Market, 1949. Wikimedia commons, pubic domain. Souk Al-Khamis (Thursday’s Market) in Qatif, Saudi Arabia is one of very few well-documented and surviving markets from Arabia.

Bazaars readapted to a new reality. Although many of them survive to this day, they have largely lost their old function as cornerstones of the economy. Instead, some bazaars shifted their emphasis from fulfilling local needs to offering souvenirs to tourists.74 Modern bazaars attempt to look like a relic of the past, but they are really a relic of fantasy. They aim to evoke exactly the sort of dreamy sensation from the Arabian Nights that European travelers sought hundreds of years ago. They cannily pretend to represent heritage, when in fact they are only reflecting to the contemporary tourist what they expect to see: the exotic and oriental market they have always dreamed of visiting. In a way, they are a living testament of Oscar Wilde’s words: “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life.” Thus, today the modern bazaar manages to survive by exploiting its past and living up to the expectations of the foreign traveler, in spite of losing much of what once made it great.

Abbad is a 2023 Curationist Critic of Color. He is a free knowledge enthusiast who contributed to the Wikimedia movement for about fifteen years. As a volunteer, he contributed to thousands of articles on the Arabic language version of Wikipedia, co-founded and chaired Wikimedia Levant, and led Arabic language translation efforts on Khan Academy. He currently works as a Knowledge Manager with the Wikimedia Foundation, helping implement the Wikimedia 2030 strategy. He authored two e-books in Arabic: "Story of Wikipedia" (2017), and "Art of Translation" (2021). In his free time, he writes on his blog and works on the manuscripts of novels, yet to be published!

Citations

Gharipour, Mohammad. "Introduction – The Culture and Politics of Commerce: Bazaars in the Islamic world." In The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, edited by Mohammad Gharipour (American University in Cairo Press, 2012), 39.

Bent, J. Theodore. Southern Arabia, Soudan and Sakotra (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1900), 19.

Philby, St John. The heart of Arabia: A Record of Travel and Exploration (Constable & Co. Limited, 1922), 19.

Gharipour, 14.

Gharipour, 13.

Gharipour, 35.

Gharipour, 14.

Gharipour, 13.

Gharipour, 17-18.

Gharipour, 14.

Baščaršija in Sarajevo is an example, where the name itself derived from the Turkish “‘Baš’” or “bazaar." See Alic, Dijana. "Transformations of the Oriental in the Architectural Work of Juraj Neidhardt and Dušan Grabrijan." PhD dissertation (The University of New South Wales, 2010), 59.

Gharipour, ed. The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, p. 14

Involved in the trade were Arabs, Persians, Indians, Jews (Gharipour, 28), Central Asians such as Bukharis, and Greeks or other Europeans. For more information on the multiple ethnicities in the Hijaz region, see Beitnouni, Muhammad Labib. Al-Rihla Al-Hijaziyya (Cairo: Al-Jamaliya Print, 1911), 16.

Wharton, Edith. In Morocco (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1920), 135.

Bell, Gertrude. Syria, the Desert & The Sown (E. P. Dutton, 1907), 321.

The One Thousand and One Nights was first translated into a European language by the French Antoine Galland in 1704–1717. See "Thousand and One Nights." Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 28 (Cambridge University Press), 883.

The same version was translated into English by John Payne, published in 1882. See Marzolph, Ulrich and Richard van Leeuwen, The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, vol 1. (2004), 506–08.

Gharipour, 13.

Watt, James. “The Origin and Development of the Oriental Tale.” Orientalism and Literature (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 50–65.

“Araby (short story).” Wikipedia, 2023, www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Araby(shortstory). Accessed 23 June 2023.

Twain, Mark. “Chapter VIII.” The Innocent Abroad (Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1869).

“Market Day Outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, www.americanart.si.edu/artwork/market-day-outside-walls-tangiers-morocco-24107. Accessed 23 June 2023.

Lynch, William. “From Beirut To Departure — From St. Jean D’acre.” Narrative Of The United States Expedition To The River Jordan And The Dead Sea (Pennsylvania: T. K. and P. G. Collins, 1849), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Narrative_Of_The_United_States_Expedition_To_The_River_Jordan_And_The_Dead_Sea/6.

Romer, Isabella Frances. A pilgrimage to the temples and tombs of Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine, in 1845-6 (London: R. Bentley, 1846) 50.

Bell, Gertrude. Safar Nameh: Persian Pictures (London: R. Bentley, 1894), 14.

Lynch.

Bell, 213.

Wharton, 51.

Wharton, 91.

Bell, 149.

Bell, 151.

Hudaiki, Abu Abdallah Muhammad. Al-Rihla Al-Hijaziyya (Rabat: The Studies, Research and Heritage Revival Center, Mohammadia League of Scholars, 2011), 89. The text was first circulated c. 1775.

Hudaiki, 81.

Twain, "Chapter XXXIII."

Wharton, 92.

Parlby, Fanny Parkes. Wanderings of a Pilgrim, In Search of the pPcturesque, During Four-and-Twenty Years in the East; With Revelations of Life in the Zenana (London: P. Richardson, 1850), 144. Ruins were also a theme that preoccupied and even charmed many people in Europe, and even inspired genres like Arab poetry’s Atlal. For a detailed account, see Rose Macaulay’s Pleasure of Ruins (1953).

“Poultry Market, Tangiers.” The Walters Art Museum, www.art.thewalters.org/detail/19983/poultry-market-tangiers/. Accessed 23 June 2023.

Gharipour, 39.

Gharipour, 25.

Gharipour, 49.

Sohoni, Pushkar. Taming the Oriental Bazaar: Architecture of the Market-Halls of Colonial India (Routledge India, 2022), 11.

Twain, "Chapter VIII."

Munroe, Nazanin Hedayat. “Silks from Ottoman Turkey.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2012, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tott/hd_tott.htm. Accessed 23 June 2023.

Al-Maknassi, Ibn Othman. Al-Eksir Fi Fikak Al-Asir (Beirut: Elsewedy Print House, Dubai & Arabian Institute for Research & Publishing, 2003), 75. First published or circulated in 1785.

Al-Ratrout, Samer & Rizeq Hammad. “Employing Heritage Elements in Contemporary Architecture - Bazaar Market as a Unique Element in Islamic Architecture.” International Journal of Research, August 2021 9 (8), 265.

Wharton, 25.

Wharton, 91.

Tennukhi, Izz Iddin. Al-Rihla Al-Tennukhiyya (Amman: Dar Al-Sha’b, 1985), 46.

Parlby, 323.

Romer, 49.

Lynch, Chapter 5.

Al Maknassi, 74.

Al Maknassi.

Al Maknassi, 75.

Stobart, Jon and Ilja an Damme. “Introduction: Markets in Modernization: Transformations in Urban Market Space and Practice, c. 1800 – c. 1970.” Urban History, vol, 43(3), August 20, 358-371. DOI: 10.1017/S0963926815000206.

Zhengan, Tan and Aw Tai Kiat. “The Role of the Traditional Market in the Traditional Islamic Cities : Case Studies of Tabriz Bazaar and Grand Bazaar Tehran.” International Journal of Engineering and Technology, November 2019 8(1.9), 624. DOI: 10.14419/ijet.v8i1.9.30074.

Sengupta, Anirban. “Emergence of Modern Indian Retail: An Historical Perspective.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, July 2008 9(36), 691.

Stephens, John L. Incidents of Travel in Egypt and the Holy Land (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1853), 15.

Wharton, 108.

Bell, 242.

Bent, 20.

Bell, 242.

Sengupta, 691.

Sohoni, 9.

Valpy, Richard. "On the Recent and Rapid Progress of the British Trade with India." Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 23 (1), 1860, 72. DOI: 10.2307/2338480.

Valpy, 74.

Valpy, 75.

Gharipour, 49.

Stobart, 360.

Gharipour, 48.

Zhengan, 625.

Stobart, 360.

Al-Ratrout, 260.

Gharipour, 49.

Abbad is a 2023 Curationist Critic of Color. He is a free knowledge enthusiast who contributed to the Wikimedia movement for about fifteen years. As a volunteer, he contributed to thousands of articles on the Arabic language version of Wikipedia, co-founded and chaired Wikimedia Levant, and led Arabic language translation efforts on Khan Academy. He currently works as a Knowledge Manager with the Wikimedia Foundation, helping implement the Wikimedia 2030 strategy. He authored two e-books in Arabic: "Story of Wikipedia" (2017), and "Art of Translation" (2021). In his free time, he writes on his blog and works on the manuscripts of novels, yet to be published!