Seaweed Through Time: Living Culture and Hidden Ubiquities

By Annie Faye Cheng•November 2025•16 Minute Read

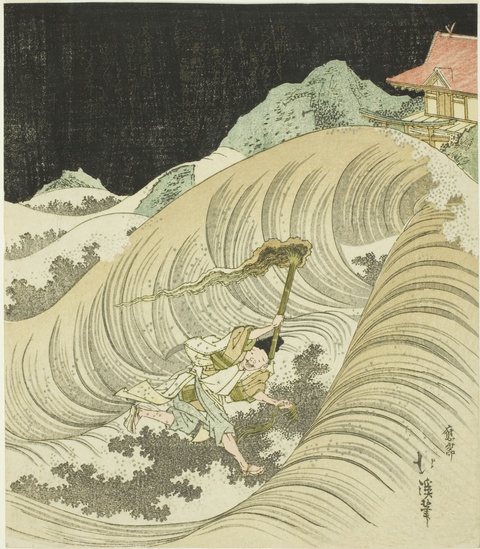

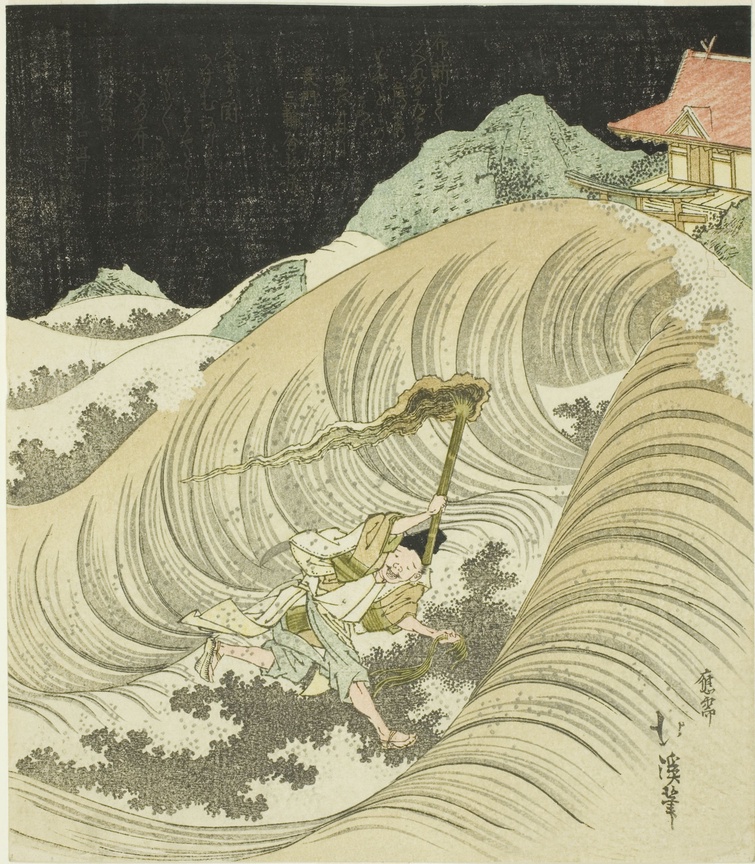

Totoya Hokkei Japanese, 1780–1850, [Shinto priest performing the seaweed-gathering ritual],(https://www.curationist.org/works/work-aioc-36447) early 1830s, Art Institute of Chicago. Public Domain.

The harvest, production, consumption, and ritualization of seaweed is a centuries-old practice. As ecosystems and cultures around seaweed evolve, how might we imagine re-imagine stewardship in the age of climate crisis?

Introduction

Seaweed has become the new darling of climate-minded scientists for its potential in agriculture and biofuel. The World Bank has released several reports in recent years singing the praises of seaweed the panacea, emphasizing its capacity to “sink carbon, sustain marine biodiversity, employ women, and unlock value chains.”1 Headlines from think tanks, academic institutions, and legacy media laud it as the “food of the future.”2 And as everyday eaters and fine-dining chefs alike turn towards veganism or plant-forward diets, seaweed has been elevated to a new position of gastronomic appreciation. Nutrient-dense and versatile in applications from direct human consumption to biofuel, seaweed fills many niches in an uncertain world.

Of course, the latest marine obsession is no new invention. There are cultures that have relied on seaweed as an edible staple for centuries, and others that are working to overcome the stigma of seaweed as a famine food. Seaweed may be the future, but it also has a storied past.

Traditions of Seaweed Use

A whopping 97% of global seaweed production comes from Asia, with 99% of that involving artificial culturing. North America accounts for less than 2% of the world’s seaweed harvest. Chile leads the production of seaweed from natural riverbeds.3 These proportions reflect the historic relevance of seaweed in regional cuisines.

Marco Bontá, Cosecha Marina, 1956, Source: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Chile. Public Domain. Two women gather cochayuyo and fish by the sea. https://www.surdoc.cl/registro/2-769

Four Thousand Miles of Coastline: Chewing Kelp in Chile

Over 14,000 years ago, off the coast of what is now Monte Verde, Chile, indigenous ancestors of the Mapuche and Huiliche relied on seaweed as a dietary staple. Scientists have carbon-dated remains of cooked kelp along with clumps purportedly chewed medicinally then discarded. This is one of the earliest documented instances of seaweed consumption.4 Cochayuyo, or the seaweed variety Durvillaea antarctica, is used for salads and stews in the ancestral diet of the Mapuche people. Marine ecologist Julio Vasquéz, told the Guardian that he estimates there are more than 800 endemic seaweed species in Chile—all of which have culinary promise given the right motivation for utilization and creativity.5

Seeking Yin in Traditional Chinese Medicine

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), seaweed is considered to have a yin cooling quality which clears dampness and detoxes the body. These medicinal beliefs are inseparable from the evolution of traditional Chinese recipes, which would consider TCM properties of each ingredient and strive for balance. As early as the 6th century CE, the influential agriculture work written by Jia Sixie, “Important Methods for the Welfare of the People" (齊民要術, Qi Min Yao Shu), included recipes for seaweed harvested from a mountainous seaside region.6

Seaweed as Ritual and Tax in Asuka-Period Japan

In the Asuka period of Japan (593–710 CE), seaweed was so valued that wakame could be used as currency. The emperors passed the Taihō Code, which allowed subjects to fulfill tax obligations through wakame in lieu of monetary payment. Similar to TCM, Japanese Shinto traditions held the culinary and nutritional benefits of seaweed in high regard, even using it as part of sacred ritual and sacrifice.7

Sacred Limu Stewardship in Hawai’i

Thousands of miles away in Hawai’i, precolonial traditions of cultivating seaweed thrived. Seaweed, called limu, was stewarded by the sacred kapu system, a set of religious and legal principles that governed social order and relationships to the land. Within the gendered expectations of kapu, women gathered and prepared many different varieties of limu. As the experts, they developed different food preparations to suit the dozens of the varieties used. Limu kala, for example, is highlighted in Ho‘oponopono forgiveness ceremonies—the algae, sometimes seasoned with turmeric and salt, is distributed to participants for prayer followed by consumption. Limu palahalaha or sea lettuce is often salted, fermented, then used to season stews.8

According to oral folklore and early Hawaiian newspapers, Queen Lili‘uokalani (1838-1917) was the first to deliberately cultivate and conserve seaweed along with other marine products. Through the Honolulu newspaper Ka Naʻi Aupuni, she announced that a few select varieties of seaweed, urchins, and shellfish that she personally propagated were not to be harvested.9 Though her individual proclamation was one of the more visible recognitions of biophysical limits in Hawai’i, overharvest prevention was always part of the broader kapu culture.

Survival Food in Coastal Ireland

While some cultures upheld seaweed as a precious part of culture and gastronomy, others turned to it primarily in times of scarcity. During the Great Famine of Ireland, now widely understood by scholars to be an act of political starvation at the hands of the British empire, coastal Irish communities turned to seaweed for survival.10

Prior to the famine, seaweed was used as manure for areas with poor soil quality, but less frequently for direct human consumption. The kelp was burned in circular stone structures called kelp kilns, and the ash produced was later used for pottery or glass production.

Unknown, The Illustrated London News 1886-04-03: Vol 88 Iss 2450, Source: Internet Archive, Public Domain. The black and white lithograph shows a group of Irish coastal foragers dressed in rags with melancholic facial expressions, harvesting seaweed.

But given a combination of potato blight and British land occupation in the 19th century, the Irish ate seaweed—which saved their lives in a time of scarcity. But as is common with those who are forced to eat certain foodstuffs out of desperation, seaweed came to embody poverty and suffering. For a long time, sea vegetables were stigmatized for their association with the famine.11

Women’s liberation and seaweed foraging in Victorian England

While seaweed was a symbol of oppression for the Irish, it meant liberation for other Victorian women. After Irishman John Ellis impressed the Princess Dowager of Wales with a seaweed sculpture in the 1750s, seaweed mania hit London society.12 Women, who were in many ways excluded from the traditional institutions of natural science, took to the coastlines.13

Species of the Kallymenia genus, left, and Ulva genus, right, from the second volume of Margaret Gatty’s British Sea-Weeds (1872), Public Domain. The scan of the original book shows botanical illustrations with a variety of British seaweeds. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/44218538

Among the most notable are Anna Atkins, an English botanist who published an 1843 book featuring cyanotypes of British algae, and Margaret Gatty, whose 1872 book British Seaweeds inspired a generation of female collectors to go “seaweeding.”14 Gatty called her “sisterhood” to explore the sea. Of the ocean, she wrote: “You are in the right dress at the right place…free, bold, joyous, monarch of all you survey, untrammelled, at ease, at home!” Some women created scrapbooks or botanical guides, while others penned scientific papers.15

The industrialization of seaweed

Over time, seaweed has transformed from a wild-cultivated and locally-harvested plant to a commodity backed by a multibillion-dollar industry.16 The industry has encountered the same pitfalls of land-based monoculture, in which the same crop is produced intensively within one contained area, usually with yield-focused, capital-intensive inputs in the form of fertilizer or mechanization. This form of production often exhausts the ecosystem in which it occurs, depleting soil quality—or in the case of seaweed, water quality and fragile marine ecosystems.

Agar as a critical war material

Unknown, Making kanten (agar) on the Kamo River, Kyoto, Japan, ca. 1880-1910, source: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, INC0617, Public Domain. The yellowed image shows the artisanal production of agar from seaweed. https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/ic/id/641/

Even the Japanese tradition of seaweed harvest became embroiled in international politics. Before World War II, Japan was the world’s primary producer of agar, a derivative of red algae used broadly in culinary, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical applications. During the war, as a result of the shortage of agar, the U.S. War Production Board deemed it a critical war material. Following the victory of the Allied Forces, the U.S. military heavily invested in Japanese agar production to return it to pre-war levels of export. Seaweed thus became key to advancing American geopolitical interests abroad, and as such the U.S. government staked an environmental and socioeconomic claim in the post-war Japanese marine ecosystem. This marked one of the important shifts of seaweed cultivation from local harvested resource to international commodity.17

Institutional Investment and Commodification of Seaweed

Such demand has also spawned corresponding interest in research on the production, processing, and distribution of seaweed, particularly in parts of the world that currently experience food insecurity or are looking to invest in more renewable energy sources. One can follow the money. In 2024, UC Berkeley allocated $13 million in funding to the newly-established International Bioeconomy Macroalgae Center alongside international partners and research councils.18

Seaweed harvest and consumption have traditionally been understood in contexts of local biodiversity, cultural ecologies, and social dynamics. But the rapid expansion of seaweed production means the sector is increasingly facing the challenges of modern agriculture.

Seaweed Snacks, Biostimulants, and the Risks of Consolidated Industrial Monoculture

In recent decades, seaweed has made its way into a broad range of industries due to its commercial versatility and relative environmental sustainability compared to other synthetic alternatives. In East Asia, seaweed shows up in food today as a packaged snack (seaweed crackers or sheets), a wrapping vessel (gimbap, sushi, onigiri), and salad or soup ingredient (miyeok-guk, liangban, and more). The popularization of these regional cuisines across the world has increased the globalized consumption of seaweed.

Annie Cheng, 2023, Dish at Central. CC-BY 4.0. Cochayuyo and spirulina seaweed dish served at Central restaurant in Lima, Peru. Central was ranked #1 in the World’s Best 50 Restaurants ranking in 2023.

For discerning consumers, seaweed has even become a luxury good—Michelin chefs pay premium prices for the hand-harvested Korean seaweed gamtae.19 In both their ubiquitous and rarefied contexts, edible seaweeds are highly desirable.

However, the utopic vision of seaweed as food of the future is threatened by the same realities of inequality that we face today. To simply duplicate the formula of industrial production with seaweed is insufficient to tackle the manifold dynamics that weaken the construction of a more dignified, climate-conscious, and equitable future.

Overemphasis on just a few core seaweed species instead of farming biodiversity replays the same cash crop mentality that exhausts soil in many terrestrial monoculture farms. While farmers have been integrating their own biological inputs for millenia—think banana peel compost or rotational grazing practices—commercial bioinputs have boomed in recent years. This strategic move, aligned with the public calls and financial realities of climate change and sustainable production, continues to consolidate agriculture into a few conglomerates. Corporations like Bayer are introducing seaweed biostimulants that further leverage its control of supply chains.20 Migrant workers in southeast Asia are plagued with the same levels of exploitation—poverty, low wages, and legal risk—as counterparts in other industries.21

And with seaweed's increasing commodification and internationalization as a resource, it may fall victim to the same challenges that face other commodity food products.22 For example, the economic emphasis on genus Pyropia, which consists of the seaweed species used for Japanese nori sheets and commercial seaweed snacks, results in high industrialization in the production process including onshore cultivation systems.23 This contributes to a dynamic of genetic homogeneity and monocultural aquaculture practices, rather than biodiversity. In some cases, the introduction of non-local seaweed varieties as invasive organisms has even resulted in environmental damage such as colonization of coral reefs or spread of seaweed disease.24

Alex Berger, December 21, 2019, Fishing the Estuary in Xiapu - China, Source: Flickr. CC By-NC 2.0. The landscape photograph shows the process of harvesting seaweed in Xiapu, China. As a leading producer, Xiapu County is known as the ‘seaweed capital’ of China.

Ultimately, the practice of emphasizing one market-favored crop comes at the cost of nurturing ecosystemic balance, longevity, and resilience to climate change. With large-scale aquaculture, labor rights are similarly an issue, with migrant laborers and local residents bearing the cost of extractive export economies.

Culture-Driven Alternatives to Industrial Seaweed Futures

In the face of daunting industrial seaweed production, a new generation of activists, scholars, historians and farmers are drawing from the past to inform the future.Historians, artists, small-scale farmers, scientists, activists, and more are reimagining different ways of engaging with seaweed. Guided by values of Indigenous science, biodiversity, gender equity, and socioeconomic justice, they enact projects that strive for sustainability in every way.

Funded by the British Natural History Museum, the three-year GlobalSeaweed-PROTECT project collaborates with Indigenous producers of Southeast Asia to enhance biodiversity, develop early warning systems for seaweed disease, restore habitats, and support local economies. Leveraging partnerships with federal governments, global universities and the United Nations, the project team developed the 2030 Seaweed Breakthrough Initiative, which proposes a biodiversity-focused global framework for sustainable seaweed production with wild and cultivated seaweed stocks.25

Forest & Kim Starr, Scaevola taccada. Limu on beach at Frigate Pt Sand Island, Midway Atoll, Hawaii, 2015. Source: Starr Environmental. CC BY 3.0. Various types of limu, Hawaiian seaweed, are strewn across the beach coastline.

The fight for sustainable seaweed is one of socioeconomic justice and dignity for the farmers, educators, land stewards, and community members that rely on it as a source of economic, nutritional, and cultural sustenance. To honor the lineage of limu growers, the University of Hawai’i’s Sea Grant program brings together local high schools, seaweed producers, startups, and cultural foundations to restore limu habitat and engage in public education initiatives around its importance.26

Magnus Manske, Women with Seaweed bags, 2005. Source, Flickr. Wikimedia Commons, Flickr user: Elitre, Public Domain. The image is sourced via USAID Africa. In a color photograph, Tanzanian women hold a line connected to floating bags of seaweed. They stand in the ocean. In the background, harvesters work on boats to gather more seaweed. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Women_with_seaweed_bags_(5762358649).jpg

In Tanzania, where significant gender gaps may hinder participation in traditional land-based agriculture, nonprofit Action for Ocean’s Seaweed Farm as a Service initiative supports youth and women seaweed farmers through focused financial investments, training, and market access services.27 In Brazil, seaweed cooperatives are transforming the language around seaweed farming to make a stance on dignity related to its cultivation; while a farmer was originally called a catador de lodo, or muck collector, today they use the word “alga” by choice.28

Seaweed is a vital lifeline for farmers that may not have access to traditional credit or land. On the island of Caluya in the Philippines, the more malleable, relatively seasonless growing cycle of seaweed has influenced the development of a kin-based credit system. For example, a seedling planted in the water can be extracted at any point to dry, sell, and access liquidity at any time. Instead of planning planting around change of the seasons, Caluyan families will plan harvest around life milestones; a large batch planted in March might be harvested in June to pay for a child’s tuition, or a late fall planting could yield bounty for a spring wedding. Raised over damaged coral systems, these seaweed farms help regenerate the base of the marine ecosystem by attracting grazing fish or offering a site for marine creatures to lay eggs.29

More Than a “Future Cash Crop”

The future of food may indeed center seaweed—but it’s a future we need to shape with intention to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Seaweed is an entrypoint into a range of other considerations of ocean biodiversity, future gastronomy, spiritualities, and living culture. In drawing inspiration from the past and honoring coming generations, today’s seaweed actors provide small-scale blueprints that provoke and inspire. These underwater forests, wild or cultivated, demand our thoughtful stewardship to thrive.

Annie Faye Cheng is a cook and writer based in Queens, New York City. She writes at the intersection of food, race, and power. More about her at anniefayecheng.com.

Citations

“Global Seaweed New and Emerging Markets Report 2023.” World Bank, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/environment/publication/global-seaweed-new-and-emerging-markets-report-2023. Accessed 1 October 2025.

McGowan, Charis. “‘Instead of Crisps, Kids Could Eat Snacks from the Sea’: The Forager Chef Looking to Revolutionise Chile’s Diet.” The Guardian, 16 July 2024. Environment. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/16/instead-of-crisps-kids-could-eat-snacks-from-the-sea-the-forager-chef-looking-to-revolutionise-chiles-diet. Accessed 1 October 2025. See also: Alex Ossola, et al. “Why You Might Be Eating More Seaweed in the Future.” Podcast series “The Future of Everything,” Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/podcasts/wsj-the-future-of-everything/why-you-might-be-eating-more-seaweed-in-the-future/14af1364-0154-41cf-bde6-46c6537867e4. Accessed 1 October 2025.

Zhang, Lizhu, et al. “Global Seaweed Farming and Processing in the Past 20 Years.” Food Production, Processing and Nutrition, vol. 4, no. 1, October 2022, p. 23. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-022-00103-2. Accessed 1 October 2025.

Fox, Maggie. “Ancient Seaweed Chews Confirm Age of Chilean Site.” Reuters, 8 May 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/lifestyle/science/ancient-seaweed-chews-confirm-age-of-chilean-site-idUSN08390999/. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

McGowan, Charis. “‘Instead of Crisps, Kids Could Eat Snacks from the Sea’: The Forager Chef Looking to Revolutionise Chile’s Diet.” The Guardian, 16 July 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/16/instead-of-crisps-kids-could-eat-snacks-from-the-sea-the-forager-chef-looking-to-revolutionise-chiles-diet. Accessed 1 October 2025.

刘光明, et al. A Kind of Production Nori Sauce and the Method for Thallus Porphyrae Broad Bean Paste Simultaneously. CN106107903A, 16 Nov. 2016, https://patents.google.com/patent/CN106107903A/en.

“Treasures from the Sea.” JCC E magazine, September 2023, Japan Creative Center, Embassy of Japan, https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/E-Magazine-Sep-2023-Seaweed.html. Accessed 10 October 2025.

Algae in Coral Reefs. https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/holomua/algae-in-coral-reefs/. Accessed 1 October 2025.

McDermid, Karla J., et al. “Seaweed Resources of the Hawaiian Islands.” Botanica Marina, vol. 62, no. 5, October 2019, pp. 443–6. De Gruyter Brill, https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2018-0091. Accessed 1 October 2025.

Bandy-Page, Wyatt. “The Ecological Underpinnings of Famine: Irish Agriculture and Land Use Under British Colonialism, 1534-1852.” Pitzer Senior Theses, 2024, https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/196. Accessed 10 October 2025.

Kraan, Stefan. “Ireland's Coastline Seaweed: Natural Heritage & Biodiversity Underwater & Maritime Heritage,” The Heritage Council, 2008,https://www.heritagecouncil.ie/content/files/irelands_coastline_seaweed_2008_4mb.pdf. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Giaimo, Cara. “The Women Who Found Liberation in Seaweed.” Nautilus, 27 March 2024, nautil.us/the-women-who-found-liberation-in-seaweed-540250/. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Giaimo, Cara. “The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Collecting Seaweed.” Atlas Obscura, 14 November 2016, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-forgotten-victorian-craze-for-collecting-seaweed. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Trethewey, Laura. “What Victorian-Era Seaweed Pressings Reveal about Our Changing Seas.” The Guardian, 27 October 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/27/what-victorian-era-seaweed-pressings-reveal-about-our-changing-seas. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Trethewey, Laura. “What Victorian-Era Seaweed Pressings Reveal about Our Changing Seas.”

New Farmed Seaweed Markets Could Reach $11.8 Billion by 2030. Press Release, World Bank Group, 16 August 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/08/16/new-farmed-seaweed-markets-could-reach-11-8-billion-by-2030. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

Riley, Joe. “The Military Forms of Seaweed.” In Holding Sway: Seaweed and the Politics of Form, edited by Melody Jue and Maya Weeks, June 2023, University of California Humanities Research Institute, https://uchri.org/foundry/the-military-forms-of-seaweed/. Accessed 6 October 2025.

Julie Gipple, “New Center To Advance Use of Seaweed in the Global Economy.”. UC Berkeley Research, 2 October 2024, https://vcresearch.berkeley.edu/news/new-center-advance-use-seaweed-global-economy. Accessed 1 October 2025.

“Why Michelin-Starred Chefs Are Paying Premium For One Of Korea’s Rarest Seaweeds | So Expensive.” Produced by Business Insider, 22 June 2024. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uSEOfPg0Ki4. Accessed 6 October 2025.

Editors, “Bayer Launches Seaweed-Based Biostimulant in China.” Fertilizer Daily, 25 April 2025, https://www.fertilizerdaily.com/20250425-bayer-launches-seaweed-based-biostimulant-in-china/. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Hussin, Hanafi, and Abdullah Khoso. “Migrant Workers in the Seaweed Sector in Sabah, Malaysia.” Sage Open, vol. 11, no. 3, 22 September 2021, 21582440211047586. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211047586.

22 Hutchins, Rob. “World’s Seaweeds Face Disaster, but Urgent Action Can Save Them.” Oceanographic, 7 May 2025, https://oceanographicmagazine.com/news/worlds-seaweeds-face-disaster-but-urgent-action-can-save-them/. Accessed 15 September 2025.

“Global Production Pyropia.” Seaweed Insights, published by Hatch Blue, undated, https://seaweedinsights.com/global-production-pyropia/. Accessed 6 October 2025.

Bhuyan, Md. Simul. “Ecological Risks Associated with Seaweed Cultivation and Identifying Risk Minimization Approaches.” Algal Research, vol. 69, January 2023, 102967. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2022.102967. Accessed 6 October 2025.

Hutchins, Rob. “Natural History Museum Leads Seaweed Resilience Research Project.” Oceanographic, 14 April 2025, https://oceanographicmagazine.com/news/natural-history-museum-leads-seaweed-resilience-research-project/. Accessed 1 October 2025.

“Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Project Actively Restoring Limu Kohu Populations Is First of Its Kind.” University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program, Sea Grant, undated, https://seagrant.soest.hawaii.edu/news-and-events/hawai%CA%BBi-sea-grant-project-actively-restoring-limu-kohu-populations-is-first-of-its-kind/. Accessed 15 September 2025. See also: Staff, HPR News. “The History and Future of Limu with Longtime Gatherers.” Hawai’i Public Radio, 19 May 2023, https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/the-conversation/2023-05-18/the-past-and-future-of-limu-with-longtime-gatherers. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Action for Ocean, “Growing an Equitable Seaweed Industry in East Africa.” The Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA), undated, https://oceanriskalliance.org/project/growing-an-equitable-seaweed-industry-in-east-africa/. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Brennan, Wren. “Cultivating Change: Women’s Involvement in a Brazilian Seaweed Collective.” Macalester College Anthropology Honors Projects, 19, 2013. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/anth_honors/19. Accessed 15 September 2025.

Arnold, Shannon. Seaweed, Power, and Markets: A Political Ecology of the Caluya Islands, Philippines. 31 March 2008. York University, Masters in Environmental Studies. YorkSpace, https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/e8056e82-8043-44d4-b7b6-6bf30dfbd64d/content Accessed 15 September 2025.

Annie Faye Cheng is a cook and writer based in Queens, New York City. She writes at the intersection of food, race, and power. More about her at anniefayecheng.com.