Protection from the Evil Eye

By Reina Gattuso•September 2025•18 Minute Read

Bangle, 19th Century. Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, CC0.

Across the world—from ancient times to the present day—people have believed in the ability of the gaze to inflict evil, and the power of precious objects to provide protection.

Introduction

The evil eye translates powerful emotions such as envy into harmful magic through the medium of vision. There are many different beliefs about curses involving the gaze worldwide, with various names for the harmful gaze including nazar, malocchio, mal de ojo, mati, and more.

Many symbols that are believed to confer evil eye protection most likely have origins in the ancient Mediterranean, Central Asia, and South Asia. Written mentions of the evil eye date to as early as the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia.1 Prominent among protective symbols is the dot-in-circle eye motif, as well as symbols like the open hand (khamsa), the bird, and the closed fist (mano fica).

By studying the similarities and differences among these objects across eras and cultures, we can trace how symbols meant for evil eye protection have circulated globally through trade, travel, and conquest. The apotropaic objects mentioned in this feature are from contexts as diverse as Sicily in the 5000s BCE, China in the 500s BCE, and 19th century Brazil. “Apotropaic” is a general term to describe rituals, spells, and objects intended to ward off evil. In this feature, we’ll take a cross-cultural look at apotropaic objects that were and are specifically designed and used as protection against the evil eye.

While the precise meaning of the evil eye has morphed across millennia, today many people continue to rely on apotropaic objects for protection and to mark important life milestones.

The Anatomy of an Amulet: Materials and Meanings

Beliefs in the evil eye demonstrate an association between the gaze and power—the power to curse, protect, or both. Thus, when creating apotropaic objects, artists and ritual specialists consider the qualities of the material as well as the power of sculptural form and motif.2

The Ambivalent Gaze

In many cultures, someone casts the evil eye by looking at another person or their possessions with envy. By desiring or admiring something, the admirer (even inadvertently) curses it. This is a potent and deeply rooted magic: people have variously attributed to the evil eye the power to curse agricultural animals,3 inflict financial calamity, cause accidents,4 and catalyze spiritual and emotional crisis.5

Prior to the acceptance of the germ theory of disease, the evil eye was widely considered a major source of physical illness.6 Today, people may utilize folk remedies against the evil eye alongside biomedical cures to address disease.7 Thus, many objects people use to protect against the evil eye are meant to ward off ill-health and welcome wellness, be it physical, spiritual, or both.

While the gaze can curse, it can also protect. There is a long tradition of affixing fearsome, staring figures to buildings in order to repel evil. For example, builders would have affixed a stone tile of Medusa, whose gaze Greeks believed turned people to stone, to a roof to protect the building.8

The Power of Reflection

In some times and places, people used shiny materials to craft amulets meant to reflect malicious gazes away from the user. For example, in the early modern Iberian Peninsula, local artists carved hard, lustrous black jet stone into small prayer beads bearing the images of Jesus Christ and Santiago (Saint James), believing the sheen of the stone would repel the evil eye.9

These prayer beads are an example of the syncretic nature of evil eye beliefs, as pre-Christian and pre-Islamic beliefs in protective magic were taken up in the material cultures of both majority Christian and Muslim societies.10

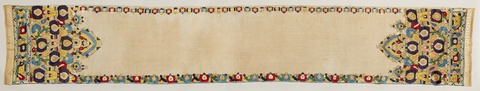

Because of their uncanny reflective abilities, mirrors figure prominently in practices around the evil eye, in contexts as diverse as Romania and Italy.11 In the 1700s, textile artisans in the city of Tetouan, Morocco, specialized in tensifa, or mirror covers, such as the one featured here. During special celebrations, such as weddings, people used tensifa to cover mirrors in order to ward off malicious gazes.12

Precious Materials (And Their Imitators)

Artists often include precious materials, believed to have innate protective powers, in apotropaic objects. In the Mediterranean, Western Asia, and Western Europe, coral—and by extension, the color red itself—is regarded as especially protecting women and children from the evil eye, as well as more generally from illness. Documentation of this belief extends as far back as the writings of Roman historian Pliny the Elder in the first century CE.13

Coral jewelry is widespread across cultures, particularly among married and mothering women. For example, coral necklaces, as the one featured here from 19th-century Yemen, were often gifted to pregnant women to promote health during childbirth.14

Because of the material’s association with evil eye protection for women and children, many medieval and early modern European Madonna and child portraits feature the infant Jesus wearing a coral necklace.15

In addition to the precious coral material, sound is also an important element in many apotropaic objects. In the Yemeni necklace, above, the jangling sound produced by the heavy silver as the wearer moved was specifically believed to confer evil eye protection.16 Meanwhile, many coral children’s objects in early modern Europe and Euro-America included a sound component, such as a gold and coral combination rattle, whistle, and bell, pictured here. This rattle would have served as both an evil eye amulet and a teething toy, demonstrating the multiple functions one object can play as adornment, status symbol, amusement, and amulet.17

Particularly in the Eastern Mediterranean and Central Asia, turquoise is also considered protective against the evil eye.18 Artists incorporated the precious stone to add potency to personal adornments, such as this 11th-century Persian turquoise and gold ring.

Those who couldn’t obtain objects made of turquoise could acquire imitations, in the hope that the color blue itself would protect the wearer even in the gem’s absence. The quartz insets in these 11th-century gold Persian earrings still include traces of blue glaze, which art historians believe was meant to imitate turquoise.19

Symbols Across Time and Place

Objects meant to protect people from the evil eye often feature one of several motifs, including the dot-in-circle eye, the bird, the open-hand khamsa, and vulva and phallus imagery. While these motifs most likely have roots in the Mediterranean, and West, Central, and South Asia, they are found on geographically diverse objects—the result of long histories of diaspora, colonization, and cultural exchange.

The Eye

The dot-in-eye motif is perhaps the oldest and most widespread symbol of evil eye protection. Archaeologists have identified dot-in-eye motifs on objects as varied as Indus Valley beads from the 7000s BCE and Sicilian pottery from the 5000s BCE. When considering objects from the deep past, we cannot be sure what these symbols meant to their makers, nor can we be sure to what extent the motifs arose independently in various contexts and to what extent they dispersed through travel.20 However, archaeologists speculate that even in very ancient times, the dot-in-eye motif served a magical function.

Variations of eye iconography were common across ancient societies from South Asia to the Mediterranean. For example, the Wedjat eye, or eye of Horus, pictured here, was a central symbol of protection in ancient Egypt. It appears commonly in the form of amulets and funerary drawings starting from at least 2600 BCE.21

Meanwhile, Ancient Greek artists commonly used the dot-in-circle motif to adorn ships’ prows as well as drinking cups, as in this vessel from the 500s CE.22 Art historians speculate the eye motif served as evil eye protection, as well as a kind of drinking game: When the drinker raised the cup to their lips, the eyes effectively became a mask transforming the drinker into a mythical being.

Today, perhaps the most widespread version of the eye motif is the blue-ringed glass nazar. This version of the symbol is found from the Mediterranean to South Asia; it is particularly prevalent in Turkey, where it is called the nazar boncuğu. A 19th-century Indian nazar in blue and clear glass on a gold band is a relative of jewelry widely available today.

While the use of the dot-in-circle motif often indicates a historical object served a protection function, that’s not always the case. Sometimes, the motif’s meaning transformed in a new context. For example, a bead from fourth century BCE China bears the dot-in-circle motif, similar to many beads from the ancient Mediterranean and Central Asia. Art historians speculate that the makers and users of this bead—perhaps borrowing the design from imported objects—may have simply regarded the symbol as decorative rather than magical.23

The Bird

Bird forms and motifs are often used in conjunction with the eye.

A spindle whorl from 8th to 10th century Egypt is adorned with multiple dot-in-eye motifs, which the artist combined to form the bodies of birds, layering symbols to greater visual—and, likely, magical—effect.24 Indeed, apotropaic objects often have multiple kinds of efficacy, where their form, function, and decoration align to promote health and repel evil.

For example, a bird-shaped Central Asian flask from the 10th to 12th centuries, adorned with dot-in-circle nazar motifs, was used to hold kohl, an eyelining powder. From ancient times to the present, kohl served many functions, including to cosmetically emphasize the eyes, to ward off eye disease, and to protect against the evil eye. The form, adornment, and use of this flask thus likely conferred multiple layers of power.

Similarly, this 12th-century Persian aquamanile may have been used to pour water for handwashing as part of sacred rituals or daily practice. The bird form, as well as the blue inlays of the bird’s eyes, may have conferred additional protection against evil.25

The Khamsa

The open hand is a common symbol of spiritual protection in traditions as dispersed as Buddhism and Hinduism and Latin American Catholicism.

In relation to the evil eye, the open hand is known as khamsa (alternately spelled hamsa). It is popular among Jewish, Muslim, and Christian people particularly in the Mediterranean, North Africa, and Central and West Asia. These cross-religious associations are revealed in the symbol’s various names, including “Hand of Fatima” and “Hand of Miriam” (or, alternately, Mary). It is particularly thought to confer evil eye protection to women and children.26

The khamsa is often combined with other apotropaic symbols, such as the eye motif, in textile and painting. For example, a painted wall panel from ninth-century Iran features complex, intertwined lines ending alternately in open hands and painted eyes.

The Vulva and Phallus

A related set of apotropaic motifs invoke genital imagery as a form of evil eye protection. The use of genital imagery, particularly vulvas, to ward off evil is geographically diverse—as in, for example, sheela na gig and dilukai carvings. Particularly in the Roman Empire and subsequent western Mediterranean cultures, phallic and vulva forms are common in apotropaic objects.27

Mano fica imagery traveled to the Americas alongside Iberian colonization, becoming part of Latin American material culture. An ornate iron horse riding bit from 18th century Mexico is adorned with dangling mano fica amulets.29

In the Americas, the mano fica syncretized with African and Indigenous magical traditions. The maker of this 19th-century Penca de Balangandã, a type of precious protective object among many enslaved Afro-Brazilian people, combined—among many charms—a mano fica and a fish symbolizing the orisha Lemanjá, a powerful Candomblé deity of Yoruba origin.30

Conclusion

Today, belief in the evil eye, and in the power of apotropaic objects to confer protection, remains strong in many communities across the world. In recent years, particularly in North America and in tourist markets in the Mediterranean and West and South Asia, apotropaic symbols—especially the blue nazar—have become more commercially popular. Some commentators attribute this resurgent popularity to a desire for cultural reconnection among diasporic communities from places with evil eye traditions.31

The diverse motivations among contemporary users of apotropaic symbols—running the gamut from aesthetic fondness to deep spiritual belief—reflect a millennia-long tradition of travel, transformation, and adaptation. Amid shifting religious and knowledge traditions, apotropaic symbols have demonstrated deep cultural resilience—a reflection, perhaps, of a persistent human need to seek protection in an unpredictable world.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

Kotzé, Zacharias. “The Evil Eye of Sumerian Deities.” Asian and African Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, 2017, p. 102. https://www.sav.sk/journals/uploads/0530144305_Kotze_FINAL.pdf. 31 July 2025.

Other senses, such as smell and taste, also inform people’s choice of protection. Pungent flavors are often foregrounded: In both southern Italy and South Asia, for example, chilli peppers are frequently believed to counteract the evil eye; they are also red in color, and phallic in shape, which may further the association (see below). Because organic materials are less likely to survive in archives, taste and smell-based amulets are harder to trace through object histories. However, we can locate these practices in pop culture and ethnography. For example, anthropologist Anthony H. Galt, in his 1982 ethnography of the evil eye in Pantelleria, Italy, writes, “One informant…carried a red chili pepper in his pocket which served as on-the-spot seasoning for pasta as well as for an amulet.” Galt, Anthony H. “The Evil Eye as Synthetic Image and its Meanings on the Island of Pantelleria, Sicily.” American Ethnologist, vol. 9, no. 4, Nov. 1982, p. 674, https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1525/ae.1982.9.4.02a00030. Accessed 31 July 2025. See also: TOI Astrology. “The Correct Method of Evil Eye Removal.” Times of India, 9 September 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/astrology/kundali-dasha-remedies/the-correct-method-of-evil-eye-removal-a-guide-to-clearing-negative-vibes/articleshow/113198618.cms. Accessed 31 July 2025.

In his ethnography of evil eye beliefs among Sicilian Canadians, Sam Migliore presents an anecdote of a neighbor casting the evil eye on a cow, making the animal ornery. Migliore’s broader argument is that the evil eye, “lu mal’uocchiu” in Sicilian, is a means through which Sicilians (both in Sicily and diaspora) articulate distress of various kinds. Migliore, Sam. Mal’uocchiu: Ambiguity, Evil Eye, and the Language of Distress. University of Toronto Press, 1997, pp. 58-59, https://archive.org/details/maluocchiuambigu0053migl. Accessed 31 July 2025.

See, for example, anthropologist Julia Elyachar’s ethnography on the role of the evil eye in popular economic life in neoliberalizing Cairo: “Value, the Evil Eye, and Economic Subjectivities.” In Markets of Dispossession: NGOs, Economic Development, and the State in Cairo. Duke University Press, 2005, pp. 144, 164, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822387138-005. Accessed 31 July 2025.

Souvlakis, Nikolaos. Evil Eye in Christian Orthodox Society. Berghahn Books, 2021, pp. 129-30, https://www.berghahnbooks.com/title/SouvlakisEvil. Accessed 1 August 2025.

Price, Lisa L. and Narchi, Nemer E. “Ethnobiology of Corallium rubrum: Protection, Healing, Medicine, and Magic.” In Ethnobiology of Corals and Coral Reefs, Springer 2015, p. 82, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-23763-3. Accessed 24 July 2025.

See Migliore’s account of a young Sicilian-Canadian woman who pursues both biomedical and magical healing from an illness, p. 56.

“Terracotta gorgoneion antefix (roof tile).” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248331. Accessed 2 August 2025.

“Prayer Bead with Christ and Saint James.” The Walters, https://art.thewalters.org/object/41.233/. Accessed 23 July 2025.

This is not without tension. For example, while modern Greek people frequently use the blue dot-in-circle eye or mati motif as evil eye protection, Greek Orthodox clergy tend to be quite critical of the practice as at-odds with proper religious devotion. See: Lower, Jenny. “Why the Evil Eye is Trending in Greece.” USA Today, 21 September 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/09/21/evil-eye-trending-greece/688973001/. Accessed 1 2025.

For example, in modern Italy and Italian America, some believe that a mirror hung near the front door will repel the evil eye before it can enter the home. While in Romania, some believe it is bad luck for infants to see themselves in a mirror, as they may give themselves the evil eye through their own reflection. See: Pagliarulo, Antonio. The Evil Eye: The History, Mystery, and Magic of the Quiet Curse. Weiser Books 2023, pp. 27, 104. Accessed 1 August 2025. See also: Dundes, Alan, ed. The Evil Eye: A Casebook. University of Wisconsin Press, 1992, p. 126, Accessed 1 August 2025..

Paydar, Niloo Imami, and Grammet, Ivo, eds. The Fabric of Moroccan Life, Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2002, pp. 67-68, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015055838844&seq=71. Accessed 1 August 2025.

Musacchio, Jacqueline Marie. “Lambs, Coral, Teeth, and the Intimate Intersection of Religion and Magic in Renaissance Italy.” In Images, Relics, and Devotional Practices in Medieval and Renaissance Italy, edited by Scott Montgomery and Sally Cornelison. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005, p. 151. Accessed 1 August 2025.

See object description from the Walters: “Necklace with Coral Beads.” The Walters, https://art.thewalters.org/object/57.2358/. Accessed 24 July 2025.

“Lambs, Coral, Teeth, and the Intimate Intersection of Religion and Magic in Renaissance Italy,” p. 81.

“Necklace with Coral Beads.”

“Ethnobiology of Corallium rubrum: Protection, Healing, Medicine, and Magic,” p 82.

Eleventh century Persian scholar Abu’l-Raihan al-Biruni noted this property in his “Kitab al-jamahir fi ma’rifat al jawahir,” “Book of the multitude of knowledge of precious stones.” For an overview of Arabic gemology and the apotropaic properties of precious stones, see: Samar Najm Abul Huda. “The Arabs and the Knowledge of Precious Stones.” The Arabist: Budapest Studies in Arabic, vol. 30, 2012, p. 104, https://arabist.hu/wp-content/uploads/articles/volume-30/Short-communication-Samar-Najm-Abul-Huda-2012.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2025. For more on al-Biruni, see: Saliba, George. “al-Bīrūnī.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/al-Biruni. Accessed 24 July 2025.

“Earring, One of a Pair.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451066. Accessed 1 August 2025.

For South Asia, see: Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. “Eye Beads from the Indus Tradition.” Journal of Asian Civilization vol. 36, no. 2, December 2013, https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Kenoyer2014%20Indus%20Eye%20Beads.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2025. For Sicily, see: Becker, Valeska. “Face Vessels and Anthropomorphic Representations on Vessels from Neolithic Sicily.” In Bodies of Clay: On Prehistoric Humanised Pottery, edited by Heiner Schwarzberg and Valeska Becker. Oxbow Books, 2017, pp. 68-70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1vgw6th.8. Accessed 24 July 2025. In eras closer to the present, however, art historians can more clearly trace the dissemination of particular motifs along trade routes.

“Eye of Ra.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eye_of_Ra. Accessed 24 July 2025.

The use of eyes to adorn ship’s prows, likely for apotropaic reasons, is very widespread, with examples from contexts as diverse as China, Sri Lanka, Yemen, and Portugal. For a contemporary study, focused on the Arabian Sea, see: Agius, Dionisius A. “Decorative Motifs on Arabian Boats: Meaning and Identity.” In Natural Resources and Cultural Connections of the Red Sea, edited by Janet Starkey, Paul Starkey, and Tony J Wilkinson. British Archaeological Reports, 2007. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/38014/Decorative.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Early 20th century anthropologists were particularly interested in the dot-in-circle motif on boats, and made several detailed studies. These studies include outdated and inaccurate ethnological theories and harmful, racist language, so they should not be considered reliable sources. The illustrations may, however, be of interest to researchers seeking documentation of eye motifs in different cultural contexts. We include a citation here, with the encouragement that the reader critically consider the work as an outdated historical document rather than an authoritative ethnography: Hornell, James. “Survivals of the use of Oculi in Modern Boats.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 53, July-December 1923. Accessed 24 July 2025.

“Bead.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/objects/155232. Accessed 24 July 2025.

“Spindle Whorl.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447348. Accessed 31 July 2025.

“Bird-shaped Vessel.” The Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1948.458. Accessed 31 July 2025.

Von Kemnitz, Eva-Marie. The Hand of Fatima: The Khamsa in the Arab-Islamic World. Brill 2023, p. 1. Accessed 31 July 2025.

For a cross-cultural overview of genital imagery as apotropaic, see: Roof, Judith. “Genitalia, as Apotropaic.” Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/genitalia-apotropaic. Accessed 31 July 2025.

“Bronze Phallic Amulet.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255092. Accessed 31 July 2025.

“Ring Bit.” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/33553. Accessed 31 July 2025.

“Penca de Balangandã.” Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2024.27. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Additionally, some attribute the rise in commercially produced mati amulets in Greek domestic and tourist economies with rising economic anxiety and a decline in institutional religious participation. See “Why the Evil Eye is Trending in Greece,” cited above. Evil eye beliefs have also accompanied diasporas, and often transform meaning when their context transforms. For the relationship between evil eye beliefs, assimilation, and whiteness in the Italian-American context, see: Buonano, Michael. “Becoming White: Notes on an Italian-American Explanation of Evil Eye.” New York Folklore, vol. 10, no. 1-2. Winter-spring 1984, https://www.proquest.com/openview/e1051a2e43c624cbd9d0b057eeabe1b1/1?cbl=1820942&pq-origsite=gscholar. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.