Gender Variations in Edo Japan

By aliwen•September 2023•40 Minute Read

Katsukawa Shunshō, The Actor Bando Mitsugoro as a Man in Sumptuous Raiment, Standing in a Field, Mount Fuji in the Background, 1778. Diptych of woodblock prints (nishiki-e), ink and color on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The rich world of the Japanese arts of the Edo Period provides insight into the varied expressions of gender and sexuality of the time, raising questions about how digital accessibility can empower newer generations to learn about the history of gender variance in the East Asian context.

During the Japanese Edo (1603–1867), many creative transformations occurred in tandem with the centralization of political power in the new capital known today as Tōkyō. Not only did colorful and thematically innovative woodblock prints widely constitute a new artform known as ukiyo-e, but artists expanded on previous techniques such as hand-crafted scrolls in order to explore erotic subject matter as never before, in a tradition that became known as shunga. Of special interest, these artifacts allow us to peer into the complexity of gender and sexual expression in Edo Japan. After the prohibition of female actors in the emerging kabuki theater in 1629, the longstanding practice of male actors in female roles known as onnagata was highly popular and often portrayed by artists. Other forms of gender variance are found in the depiction of third gender wakashū, which were male youths that occupied an androgynous role in society and were often courted by both male and female lovers.

This essay takes the form of a case study of the Curationist's multi-institutional artistic digital database as of June 2023, creating eight curated collections focusing on gender variance and sexuality during the Edo. In order to do so, I first describe the language resources in Japanese developed to name and describe gender variance. I also address two major cultural touchstones through key images of Mount Fuji and kabuki actors. The essay then critically analyzes the eight collections and the tendencies in the metadata and archival ontologies used to describe these artifacts. Finally, I offer some critical interventions and potential ways forward.

Researching Gender Variance, Crossdressing, and Third Gender Representations in the Artworks of the Japanese Edo Period through Online Databases

Language, Gender, and Sexuality in the Japanese Cultural Field

In current Japanese-speaking communities, there is a vast array of possibilities when describing non-normative sexual identifications—the plurality of gender expression and sexualities that do not fall in line with the male/masculine-female/feminine binary that is often uplifted and naturalized by cis-(hetero)patriarchal societies.

Often, people who do not identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, gender nonconforming, or allies themselves have some difficulty with the expansive use of acronyms in the politics and celebrations of sexual minorities across the globe. And this is with due reason, as the politics of sexual minorities and their practices should not be considered as a single unified entity. The community of identities that make up these movements are not unanimous in their ideas or objectives, nor are sex-gender differences inhabited and interpreted equally throughout different regions and territories. This polyphonic, additive (as opposed to reductive) approach to political relationality and the language used to typify and describe sex-gender difference is also territorially and―thus―culturally specific.

The abundant language available in Japanese to describe gender variance and sexual practices has a twofold tendency, including not only native language constructions but also foreign concepts that are many times transformed using the katakana alphabet, the romaji or roman alphabet, or the combination of both, providing a local linguistic perspective on globally relevant terminology.

In this category of localized foreign concepts, terms such as ジェンダー (Gender), Xジェンダー (X Gender), ジェンダーバリアンス (Gender Variance), ジェンダークィア (Gender Queer), クィア (Queer), and トランスジェンダー (Transgender) are all used in both academic and everyday speech to varying degrees, describing the ways in which certain subsets of gendered individuals might subvert the presentation and bodily stereotypes upheld by binary societies. Since 23 January 2019, Japan’s Supreme Court has allowed postoperative transgender people with gender-affirming surgery to legally change the gender markers in their legal identification credentials,1 creating multilateral questions about tolerance, but also about sterilization and transmedicalism2 as gateways to civil liberties such as gender recognition and civil unions.

Another tendency in the Japanese language describes gender variant people using concepts developed inside of their own discursive systems, often including 漢字 (kanji) Chinese characters to illustrate complex or abstract ideas represented in discrete parts that relate and modify one another. Since at least the Taisho Period (1912–1926), in translations of Western medical texts regarding homosexuality or same-sex attraction, the word 同性愛 (dōseiai) has been used to describe this sexual phenomenon.3 However, when unpacking the etymology of the characters contained by the word, the connotation is much less clinical or pathological in nature than its Anglo-Saxon counterpart, as a direct translation would be “same sex love.”

However, even more native usages that include the character of 性―roughly desire, sexuality, or nature―can be used to describe many different configurations of gender presentation:

a) 両性具有 (ryōsei guyū), which can be used to describe someone androgynous or even intersexual individuals,

b) 第三の性 (dai san no sei), which literally translates as third gender,

c) 両性 (ryōsei), which can be used to describe androgynous or gender fluid people,

d) 中性 (chūsei), which can be applied for gender neutral or nonbinary people,

e) 無性 (musei), used for agender identifying individuals, a long etcetera.

Other terms are more controversial, as they can be deemed slurs by the educated middle class, but are reclaimed or used colloquially among insiders in other circles, including “gay” nightlife culture: this includes concepts such as ニューハーフ (nyūhāfu) or “new half," which is often used to describe male-to-female transexual people or crossdressing female impersonators, as well as オネエ (onē), which is an umbrella term used to describe femme, “sis,” or “queen” identities. Further along the contested side of the linguistic spectrum, terms such as お釜 (okama), which is a term traced back to the Edo Period (1603–1867) and is used to describe gay/sissy or feminine men, or its derivation お鍋 (onabe), to describe the butch-presenting female counterpart, have their word origin in kitchen appliances used analogically to people questioning fixed gender assignments, and cause misunderstandings when used among the general public.4

Considering the rich language in Japanese to name the ways in which people question the gender binary, an interesting opportunity presents itself in revisiting the art history of Japan in order to inquire about the presence and representation of gender variance in different periods.

Images of the Floating World: From Hokusai to Shunga

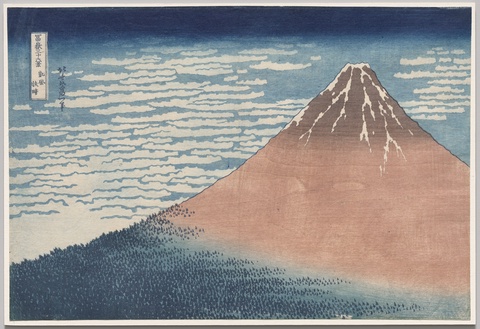

When thinking of the global perception of the culture of 日本 (Japan), two of the most pervasive images that come to mind are Mount Fuji and kabuki theater. The glorious 富士山 (Mount Fuji) is a natural summit of great social and spiritual significance for Japanese people, portrayed time and again by countless artworks. The centuries-old tradition of 歌舞伎 (kabuki) theater, with its intricate makeup, costuming, and staging, as well as its dramatic performances set to the tune of sometimes eerie music and song, is represented often through depictions of actors on and off stage. However, most of us have been introduced to these important landmarks of Japanese life through the imagery made by artists. This brings a third cultural landmark to the forefront: the beloved tradition of Japanese woodblock prints, and how these representations of Japan’s territorial and cultural landscapes have been disseminated for a local and a worldly audience alike.

An intersection between Mount Fuji, kabuki theater, and woodblock printing is encapsulated by one of the most recognizable Japanese artists of all time: 葛飾 北斎 KATSUSHIKA Hokusai, who is believed to have lived between 1760 and 1849 during the height of the Edo Period. The 江戸時代 (Edo Period) (1603–1867) was an era of artistic and cultural renovation and economic growth for Japan, as well as strict isolationism. This period originated with the consolidation of the disparate feudal 将軍 (shōgun) states under centralized power, which was concentrated in the new capital city transferred from the “thousand year capital” of Kyōto (京都) to the merchant city of Edo (江戸), known today as 東京 (Tōkyō). Among Hokusai’s most famous works, his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (『富嶽三十六景』), are ever present in the zeitgeist of Japan’s imagery, as are his representations of famous kabuki actors and even his most infamous erotic pieces, including The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (『蛸と海女』) of 1814. Although it is not the first work to artistically explore the eroticism of creatures with tentacles interacting with humans, it is still regarded as an early bastion of the tentacle pornography subgenre.5 6

Hokusai’s most remembered medium of expression was the elaborate Japanese technique of woodblock printing (木版画), which gained an intricate and colorful iteration by the mid-1700’s to mid-1800's, consolidating what became known as the ukiyo-e (浮世絵) artistic school; which could roughly be translated as “images of the floating world.” This “floating” sensibility is present in the urban and permissive subject matter of the artworks―often depicting the theater, hedonism, and everyday city life. Of particular interest, many sophisticated pornographic creations which are categorized under the umbrella term of 春画 (shunga)―roughly “images of spring”―surged during the Edo, taking advantage of both the advances and popularity of woodblock printing and some paintings, as well as the aforementioned handscrolls, which were aptly suited for private consumption.7

A Curious Diptych: Kabuki and Mount Fuji

However, other peculiar genealogies can also be traced back by focusing on the preserved artifacts of this period. For example, if we look at the captivating work of the artist 勝川 春章 (KATSUKAWA Shunshō)(ca. 1726–1793) we can find some interesting depictions of gender and sexuality from the time.

In his diptych from circa 1778, the ever-present Olympus of Mount Fuji towers in the background of the composition. Its imposing symmetry constituted by both colorful 錦絵 (nishiki-e)8 prints is not mere background but is central to the artwork’s presence and meaning. To the left, probably the acclaimed kabuki actor 二代目坂東 三津五郎 (BANDO Mitsugoro II),9 interprets the role of a nobleman looking at a luscious field at the feet of holy Mount Fuji. Although the original Japanese title is missing from the metadata of the entry, we instead get the rambunctious translation (or interpretation) of The Actor Bando Mitsugoro as a Man in Sumptuous Raiment, Standing in a Field, Mount Fuji in the Background— certainly a colorful choice that could have been based on a certain scene from a kabuki play.

To the right, the diptych is completed with the presence of another figure. If the male presence to the left is assertive, stern, and regal, the female figure seems more sly, coquettish, and sophisticated. Applying modern terms, the figure is performing femininity and womanhood through factors such as cosmetics, attire, accessories, posture, and demeanor. The feminine straw hat protects the pallor of the skin from the “low class” bronze gained from working on the fields, under which we observe a complexion painted with a heavy white base and small, puckered lips in crimson. This sense of beauty through artifice evokes the kabuki stage, or the makeup of highly skilled artists and entertainers known as 芸者 (geisha) or 花魁 (oiran).10 The sartorial choices and footwear of both figures would not be very well suited for an outing to the foot of Mount Fuji, which imbues both prints with a sense of fantastical whimsy.

The feminine figure in the right of the diptych is probably 初代中村 富十郎 (NAKAMURA Tomijûrô),11 an acclaimed kabuki actor specializing in 女方 (onnagata) roles,12 in which assigned-male-at-birth actors would embody female (or, better yet, exaggeratedly feminine) roles. The available metadata of this particular part of the aforementioned diptych again lacks a title in Japanese; instead, in a rather unlucky turn of phrase, we get The Actor Nakamura Tomijuro as a Tall Woman in a Flat Straw Hat.13 My research on the museum site has not yet recovered the original Japanese title, but something tells me that most Japanese woodblock artists of the time would not be surprised or at all shocked over the “stature” of said female figure, being that many of them―including most definitely the great Shunshō―would often depict, or one could even say had a relative enchantment with, the female-impersonating actors of kabuki theater such as the one actor here represented. The question then arises of when and how did this “tall” adjective become attached to the work, as the drag illusion of kabuki would not be much of a taboo among the uninitiated and enthusiasts alike, but rather a standardized mandate and cause for gawkful admiration?

The Untapped Potential of Databases in Researching Gender Variance in the Japanese Edo

From Elizabethan theater to the Japanese Edo kabuki to New York City drag balls in the 1980’s and 90’s, many cultures and eras have offered different forms of gender presentation. Those including female impersonation or drag have been an important and constant―yet often misunderstood―asset of human cultural forms and production, as well as a crucial component of people’s individual identity even outside of the limelights of the stage or the ballroom. In addition to the evergreen intrigue of kabuki onnagata female impersonators, or the third gender wakashū,14 sex and sexuality as well as gender are vital components of theatricality and art both then and now.15 Today, a new form of massification of culture is occurring, much like the way in which the techniques used in the ukiyo-e of the Edo Period provided a previously unmatched access to viewing art throughout social classes and material conditions. What are the possibilities and potential challenges of current cultural and artistic institutions providing access to digitized versions of their artifacts related to gender variance and sexuality?

Encryption, Metadata, and Ontologies: Curationist as Case Study

From the 4.4 million works featured on Curationist, this essay showcases a series of eight curated collections, tracking down gender variance and sexuality in the artworks of the Japanese Edo. In order to create these collections, idiomatically specific search terms where used, such as: “江戸時代” (Edo period), “浮世絵” (ukiyo-e), “錦絵” (nishiki-e), and “巻物” (makimono). Japanese search terms using Chinese characters proved more efficient over English search terms, which at times provide more ambiguous results for this type of research. A sufficient sample of works was sourced, an initial survey of the way that gender variance in Edo Japan can be accessed and reviewed through search engines linked to contemporary cultural institutions. Other useful search terms were the names of acclaimed artists of the period who often represented gender variance, including the likes of 石川 豊信 (ISHIKAWA Toyonobu), 勝川 春章 (KATSUKAWA Shunshō), and 西河 吉信 (NISHIKAWA Yoshinobu), complementing the initial concept-based search with creator-driven searches. The total number of works in these eight collections is around 175 entries, with the disclaimer that some artworks are cataloged more than once by their host institutions.

Now let us describe some of the categorizations, reasoning, and artifacts contained in some of these collections.

Gender Variance and Sexualities in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) and Other Related Artifacts

The largest category of artworks found in the Curationist partner archives which represent gender variance or crossdressing from the Japanese Edo were undoubtedly woodblock prints. This result is to be expected, as prints were widely available and reproduced for a massive audience. Other more “auratic” or singular artifacts such as paintings or scrolls are obviously unique works and their preservation and availability is thus rarer. Under this collection, all the available artifacts found have been cataloged, including depictions of sexuality, kabuki onnagata, third gender wakashū, or the intersections between all these categories, in artistic mediums such woodblock prints, books, paintings, objects, and scrolls of different orientations.

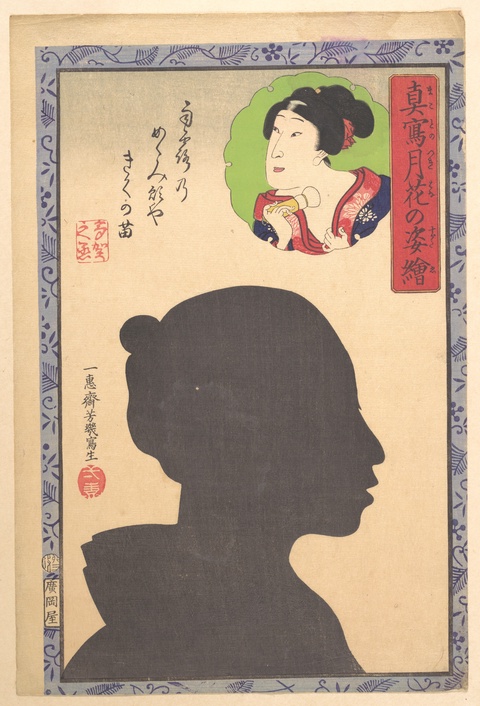

The first general collection on gender variance during the Edo has been illustrated with a woodblock print by the artist 歌川 芳幾 (UTAGAWA Yoshiiku) (1833–1904). His life spans the Edo and Meiji periods. The date of production of this work and the series to which it belongs cannot be pinpointed accurately, although it is considered to be Meiji period (1868–1912). However, they all represent shadowy profiles of renowned kabuki actors of the late Edo. This innovative artwork shows the undying appeal of kabuki onnagata crossdressing from the Edo and the celebrity of actors who specialize in this type of crossdressing roles. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art owns six related works from this shadow portrait series, but the series is left untitled and more information is lacking from the metadata.16 When contrasting the available metadata provided by the Met with the records for the same series at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston, we obtain a whole new set of information about this artwork.17 We learn that the complete series consists of 36 silhouettes and that the series is titled『真写月花の姿絵』, which they translate as Portraits as True Likenesses in the Moonlight. They have narrowed down the year of production to 1867, one year before the start of the Meiji era. Of course, this may not be the case of the print owned by the Met, which could potentially be a reproduction from a later date.

This particular print is described as a 姿絵 (portrait) of the beloved onnagata 二代目尾上 多賀之丞 (ONOE Taganojō II) (1849-1899). The head shows a softness and well-balanced roundness that contrast with the slightly harsher profiles of the male-role actors depicted in the series, and ONOE Taganojō II―who would have been just under 20 years of age when the work was produced―appears very “stealthily” as a woman. Even the eyelashes of the actor are represented in a soft downward angle similar to that of the fine nose, which end over shapely lips. Towards the top right, a 月花 (moon-flower) window presents another rendition of the same actor. The yellowy-green background of the moon-flower window makes the hot pinks and reds that make up his hair ornament, lips, and kimono stand out. Clearly, this version of the actor is preparing for the kabuki stage. A regally ornamented updo was probably created through the use of hairpieces; peeking through the crown of the hairline, one sees a grayish-white oval color. This could be referencing a shaved head under the wig, in line with the presentation mandate of the 丁髷 (chonmage) shaved hairstyle for high-ranking men during the period.18 With a candid expression and sensual demeanor, the actor happens to be revealing the high portion of his cleavage while stippling thick coats of white base makeup to his neck, adding to the vivacity and titillation of the piece, which would have been highly coveted by the fans of the actor. This open display of the artifice used in the construction of gender presentation, as well as the haunting and relatively naturalistic presence of the actor created through the silhouette technique, demonstrates how the arts of the late Edo do not only tolerate, but provide generous space and longing for the presence of gender variance.

Crossdressing (女方) Kabuki (歌舞伎) Actors and Other Related Artifacts

The next curated collection is a more focused exploration of the onnagata crossdressing and other related phenomena of yarō-kabuki. (Note that this and the following collections include some objects that are also included in the more general “Gender Variance and Sexualities in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) and Other Related Artifacts” collection.) A highlight from this collection is a woodblock print that complexifies the notion of crossing gender boundaries on the kabuki stage: The Actor Arashi Wakano as a Wakashu (Youth) in a Kappa (Raincoat) by 西河吉信 (NISHIKAWA Yoshinobu). This work is also from the Met. The print from circa 1725 shows the onnagata known as 初代嵐 若の (ARASHI Wakano). Here, he is not crossdressing as a “woman,” but rather interpreting the role of a third gender wakashū youth. We can observe this since, after the ban of wakashū actors in kabuki, thespians were expected to have come of age and to have shaved off their long forelocks: thus the actor wears a 紫帽子 (murasaki-bōshi) or 野郎帽子 (yarō-bōshi) headscarf to cover his shaven head while on stage. These headscarves, which were often of a grayish-purple hue, were used in the yarō-kabuki stage by actors who interpreted onagatta crossdressing or third gender wakashū roles. They were often imbued with an erotic appeal for their followers. The actor looks exquisitely androgynous while holding an ornate umbrella that would not have been uncommon for ladies of high status at the time. The actor shows an extravagant demeanor as he twists towards a left profile of the face while prancing with a forward step, the left arm raised and the hand coyly tucked away inside of the raincoat sleeve, the right arm also raised holding the umbrella.

Emergent Categories

While researching crossdressing kabuki actors, further iconographic coincidences were noted and inspired subdivisions to the previous collection into emergent categories that highlight actors in nature, actors wielding weapons, and actors dealing with the supernatural. The one with the most entries is “Gender Variance and Sexualities in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵)- Crossdressing Kabuki (歌舞伎) Actors in Nature (自然),” in which the imagination of the artists of the period represent onnagata roles that would of course be performed on a stage, and transport these narratives onto what appear as natural landscapes. Cherry groves in full bloom, twisting riverbanks, and frozen forests are some of the locations, and even other artifacts represent actual identifiable places in Japan including the base of Mount Fuji. Another emergent category is that of “Gender Variance and Sexualities in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) - Crossdressing (女方) Kabuki (歌舞伎) Actors and the Supernatural,” which is a category with rather fewer entries. The depictions of haunts, ghouls, imps, and other fantastic creatures often referred to as 妖怪 (yōkai) in Japanese lore are striking in juxtaposition to onnagata in kabuki plays.

The artwork I have chosen to illustrate this emergent classifications portion is from yet another collection, titled “Gender Variance and Sexualities in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) - Crossdressing (女方) Kabuki (歌舞伎) Actors Wielding Weapons.” This category has even fewer entries, although is no less significant for that matter. As a contemporary art historian looking back at the Japanese Edo, while I was researching and curating this collection I could perceive a growing conservative radicalization in the Global North and geopolitically marginalized territorialities against the existence of transgender-identifying people such as myself, in tandem to the related practices of drag, female impersonating, or crossdressing, which have also become exceedingly persecuted and demonized. I felt a strange solace in gathering the works for this collection in which the often submissive onnagata roles are subverted with the appearance of weaponry that suggest hostile retaliation, including one with a highly ornamented 薙刀 (naginata) Japanese lance, and three others wielding the 刀 (katana) usually carried by 侍 (samurai) warriors. One piece of note is a woodblock print by the renowned artist Shunshō. He created the aforementioned diptych at the foot of Mount Fuji in the same year, 1778. Once again, the available metadata at the Met only provides an English translation for the title without the original kanji characters, which reads as The Third Segawa Kikunojo as a Woman in a Crouching Position.19

The work depicts the famed onnagata known as 三代目瀬川 菊之丞 (SEGAWA Kikunojo III) (1751~1810)20 in a low crouching position with an erect sword, ready to strike in the midst of a violent confrontation. Behind the central figure, a winding river that could be slightly unruly, as shown by the expressive and twisting black strokes, adds a psychological metaphor of an agitated state. The presence of the river and vegetation position the figure in an exterior, and yet the hair and kimono are billowing and extravagant in a slightly antiquated fashion that points to the 十二単 (jūnihitoe) used during the Heian Period (794–1185), which wouldn’t have been very well suited for outside of a palace.21 The two-layered hairstyle is Heian, too, with the long extension of the hair that extends past the wearer’s knees, and the shorter layer additionally framing the face. However, the very crown of the head is covered with a headwrap, implying that the actor is duly shaven as required for men during the Edo. This superposition of historical periods―Heian and Edo―is synthesized in the image of the feminine presenting figure in a combative position: creating a point of connection between two temporalities of Japanese history which pushed the envelope in terms of the conventional normative gender roles through artistic explorations of sensuality, eroticism, and pathos.

Third Gender Wakashū (若衆)

The next curated collection relates particularly to third gender wakashū individuals. This collection illustrates that gender fluidity during the Edo was not limited to female impersonation for the theater, but that conceptions of age, social role, and sexuality were more complex during this period then the restrictive gender binary that is many times reinforced and policed by patriarchal societies. Among the examples recognized, I have chosen to exemplify the collection using a unique painting rather than a popular woodblock print: the Met’s exquisite 掛物 (kakemono) hanging scroll titled『武士と若衆』(Samurai and Wakashu (Male Youth)) by 宮川一笑筆 (MIYAGAWA Isshō) (1689–1780).22 This marvelously preserved painting, dated to the beginning of the 18th century, features two figures interacting in an intimate interior location, with a hanging houseplant in the upper right corner and a carpet that grounds everything else in the painting. The intimate and slightly disheveled scenario gives the observer a sense of voyeuristic intrusion into a quarrel between lovers, presenting an interesting power dynamic between both figures. The older warrior lord seems to hold a pleading position, grabbing onto the younger wakashū figure’s long, flowing 振袖 (furisode) sleeves. In a visual representation of their power play, the wakashū youth is standing up to suggest an upper hand in the relation similarly to a noli me tangere in Christian iconography, with the body turned toward the left edge of the image to suggest that they are decidedly leaving the interaction. The same is suggested by the black and gold obi sash that appears long and feminine as well as hastily tied up in a loose knot, implying that the figure could have been undressed moments before. The rest of the kimono is extravagant and luxurious, with a pure white underlayer below a gold and black kimono with vertical stripes, topped by a beautiful floral patterned overlayer. The beautiful, androgynous face of the wakashū looks back at the older man to the right, with what looks to me to be an impassive glare, over softly rouged lips. The ornate hairstyle with the waved seagull’s tail pattern at the nape and high forward-leaning mage knot accent of the crown is suddenly interrupted by the grayish-purple yarō-bōshi headscarf, waking us from the artifice of the scene by making us aware that the wakashū represented is not actually a third gender youth, but a kabuki actor interpreting one.

This piece is a marvelous depiction of the fantasy, eroticism, and multilayered strata of gender presentation that come into play in the ukiyo-e school of the Edo. When revising other pieces of the collection of Japanese art at the Met, we find a striking iconographic coincidence in another hanging scroll titled Kabuki Play Kusazuribiki from the Tales of Soga (Soga monogatari).23 This depicts a scene from the tale known as 曾我兄弟の仇討ち (Revenge of the Soga Brothers) or more simply 曽我物語 (Soga Monogatari),24 in which two brothers vow to avenge their father’s murder. Many inventive and playful artworks from the Edo period repeat this iconography of the older warrior detaining the younger, more impulsive young man by tugging on his clothes (known as 草摺引 or kusazuribiki)25 in alternative gender and sex configuration using the trope established by the Soga story painting. This trope was a means by which artists explored the power dynamics between presumed lovers for a sophisticated viewership who could see the humor in images such as one of a woman holding on to a wakashū’s sleeve,26 or another case of an older man pulling on the sleeves of a woman.27

Gender and Sexuality in Shunga (春画) Scrolls (巻物), Ukiyo-e (浮世絵), and other related artifacts

By far the most difficult collection to piece together, but one of the most exciting―every pun intended―is the collection dedicated to shunga erotica of the Edo. In it we can find a variety of items including albums or books, prints, and even an inscribed knife. One piece that can illustrate this collection is Demonen, or Demons, an anonymous woodblock print dated circa 1808 found at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands.28 This piece has been compared to the works of 歌川 国芳 (UTAGAWA Kuniyoshi) (1798–1861). It depicts a series of two opposing bands of yōkai demon-like creatures amidst a confrontation. However, under further inspection, the ghostly bodies of these creatures are constituted by multiple phallic and yonic iconographies. This type of intermixing of the “grotesque” with the supernatural and the erotic is not uncommon in Japanese art history, nor Japanese contemporary art, and may have as a partial influence certain playful currents of Buddhist art which often depicted human sexual anatomy. The print is said to belong to a series of twelve that revolve around the story of 源 頼光 (MINAMOTO no Yorimitsu), most commonly referred as Raikō, being terrorized in his sleep by the 土蜘蛛 (Tsuchigumo) Earth Spider Yōkai which in turn provides the hero with horrible nightmares. Many of the pieces of this curated collection were found at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands.29 Unfortunately, either they choose not to provide access to the erotic contents past the cover of their compaginated pieces (which are most), or for some digital access reason only the cover appears available. In this collection in particular, I believe that the same piece is cataloged repeatedly, which is an erotic bathhouse set attributed to the great UTAGAWA Kuniyoshi from around 1830.

An eighth collection titled “Views of the Kabuki Theatre (歌舞伎座) Through Time” provides context for the gender variance depicted on stage pointing to the necessary social context for this specific expression of gender fluidity.

Can Metadata and Ontologies Aid or Obscure the Presence of Gender Variance in Japanese History?

After researching and curating these collections, I have synthesized my observations and suggestions about the possibilities and challenges of metadata and ontologies in our current information systems in two main points.

Lost in Translation

There is a clear language barrier that impedes the correct interpretation of some of the digitized entries of the curated artifacts representing gender variance from the Japanese Edo. This is of course in great part due to the fact that these artifacts are culturally specific, and that the history, transformations, and usages of the Japanese language and its multifaceted writing systems are a key element in recognizing and inscribing the cultural traditions and practices surrounding the production of these artworks. People interested in viewing and learning about the art and sexuality of the Japanese Edo should not need to be fluent in Japanese, or even its historical fluctuations through the centuries. And those who are should be allowed to access that kind of information, too. Metadata needs to be more sensitive in providing a more culturally and linguistically attuned body of information. This should include making available accurate metadata in the mother tongue of the cultural institutions that own and preserve these artifacts―such as English or Dutch―as well as in the language of the artwork’s own culture. This can help us to best identify the artists that have been involved with the production of the artworks, the exact titles given to said artworks at the time (which often correlates with the iconographies or personalities represented in the work), as well as other relevant paratextual information linked to the intention of the works including which exact kabuki actors, plays, and scenes are being represented, as well as the means of acquisition and preservation of the artifacts in their respective catalogs.

This is the case for the Met’s Silhouette Image of Kabuki Actor woodblock print representing onnagata ONOE Taganojō II, which is not specified by their metadata. I am grateful for the accessibility that digitization and databases provide for researching these periods and works. However, there is still room for improvement in the digital textual and descriptive entries. It bears repeating that the metadata entry at the MFA Boston for another version of the same print is much more thorough and includes more refined dating and ekphrastic description, and they have kindly translated some of the kanji characters from antiquated usages to more current ones, including those in the title of the series: 寫 has been replaced with 写, and 繪 has been replaced with 絵, which permits modern Japanese readers to understand fully.

Euphemisms

A second layer of complexity is added when the original cultural and linguistic content is further complicated by “equivocations” in the attributions imprinted on these artifacts. To return to the Met’s “tall” lady, instead of using “tall,” the attribution might do better to refer to them as an onnagata performer. Rather than using circumlocutions to talk about an actor appearing “as a woman,” or “as a youth,” it would be better to refer to onnagata or wakashū figures even with roman letters to avoid confusions or misgenderings that do not aid in the historiographical precision and contextualization of said artifacts. Furthermore, including more detailed specifications about the paradata of the aforementioned pieces―particularly the provenance or “acquisition and donation histories” of the artifacts―can allow the queer scholar to point towards the correct sources of confusion in the gender and presentation of gender variant figures, which are a fundamental component of Edo era cultural production.

Before signing off this meditation on gender variance during the Japanese Edo, I must make the disclaimer that while the Japanese collection of the Met displays some inconsistencies in their current metadata, the curator of the collection has endured a commendable feat in acquiring and (concurrently) preserving and making available artworks representing gender variance through Japanese history. With a superposition of patriarchal oppression and biases throughout Japanese history and the Western institutions that have acquired their art, it is often possible that the artifacts representing what could be considered from a contemporary lens as non-normative gender identities and sexualities can be shunned from the official art historical discourses. The Met has created a formidable hospitality and interest in the gender variant art of Japan, and my commentary should be interpreted as a call to action for a progressive improvement of the metadata protocols and descriptions surrounding their invaluable collection and those of similar institutions: allowing contemporary critical gender theories to expand upon and add precision to the framing of their artifacts.

Gender Variance in the Metadata of Japanese Art History

During this research project, I have purposefully shied away from applying certain terminology that is more often used in gender and sexuality studies, both in the Anglo-Saxon and Japanese spheres. Although I have made explicit my transfeminist and queer methodological inclinations and readings, I have instead preferred the term “gender variance”―even pushing for the uncommon but still useful ジェンダーバリアンス in Japanese katakana―in order to both create an inclusive terminology that can evoke a myriad of human gender identifications, sexual practices, and desires, while taking advantage of the newness of this term in this particular context so as to be able to project incisive questions from the sort of tabula rasa that is encompassed by the emerging field of metadata studies. This perspective still is prone to error: including sample sizing, availability, and accessibility to adequately preserved and licensed artifacts, or for instance the glaring underrepresentation of female-to-female love and sexuality, or that of assigned-female-at-birth individuals that chose to question or subvert expected gender presentations of their historical time periods. However, by embracing the concept of “gender variance” in Japanese and East Asian art histories, the presence and stories of individuals that add nuance to our understanding of gender and sexuality in the region can empower a new generation of digitally native researchers and historians: to not only shed light on the silenced histories of gendered Others, but also to advocate for our longevity and revolutionary artistry in the face of continued adversities warranted by the sociopolitical status quo: when revisiting windows of time in which our presence was, however codified, vitally present and even celebrated.

aliwen is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. aliwen is a non-binary artist, critic, curator, and writer from Chile, currently based in Tokyo. Their research themes include the artistic representations and cultural heritage of queer, gender-variant or transgender people in regions such as Latin America and East Asia. They obtained their BA in Art Theory and History from The University of Chile, and received their MA in Art Studies and Curatorial Practices from Tokyo University of the Arts. Their first book Barricade Criticism. Body, Writing, and Visuality was published by Brooklyn/Santiago-based publisher Sangria Legibilities in 2021. Their recent projects include the Visual AIDS 2022 Research Fellowship.

Suggested Readings

Bohnke, Christin. “The Disappearance of Japan’s ‘Third Gender’.” JSTOR Daily, www.daily.jstor.org/the-disappearance-of-japans-third-gender/.

Gattuso, Reina. “The Learned Courtesan in Edo Japan.” The Curationist, https://www.curationist.org/editorial-features/article/the-learned-courtesan-in-edo-japan.

Hasegawa, Yuko. “Grotesque and cruel imagery in Japanese gender expression – Nobuyoshi Araki, Makoto Aida and Fuyuko Matsui.” The Persistence of Taste: Art, Museums and Everyday Life After Bourdieu. Malcolm Quinn, David Beech, Michael Lehnert, Carol Tulloch, and Stephen Wilson, eds.

Long, Daniel. “Formation Processes of Some Japanese Gay Argot Terms.” American Speech, vol. 71, no. 2, 1996, pp. 215-224, www.jstor.org/stable/455489.

Pflugfelder, Gregory. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press, 1999.

Citations

“Japan: Law Requiring Surgery for Legal Change of Gender Ruled Constitutional.” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2019-04-12/japan-law-requiring-surgery-for-legal-change-of-gender-ruled-constitutional. Accessed 7 August 2023.

Transmedicalism is a polarizing ideological, and thus political, tendency in the discourses surround transness and transgender experiences, in which it is believed that the transgender condition is based on the concrete and pathological experience of gender dysphoria―in very rough terms, experiencing negative feelings and symptoms towards the development of anatomical or secondary gender traits in someone’s own body, the feeling of “being trapped in the wrong body”, etcetera―which requires for a series of medical interventions or therapies, including hormone replacement therapy, voice training, gender-affirming surgeries such as mastectomies or genital reconstruction; in order for the individual struggling with dysphoria to best adapt to the (binary) gender with which they identify. Due to the scope of this research, I will not be able to delve deeper into the potential legislative benefits and the negative gatekeeping and binary gender policing that arise from the transmedicalist perspective.

“During the first decades of the twentieth century, [the categories of ‘same-sex love’ (dōseiai) or ‘cross-sex love’ (iseiai)] came largely to replace the older division of sexual topography into nanshoku and joshoku hemispheres. While the two mappings overlapped to a certain degree, they were not coextensive. The nanshoku/joshoku dyad was patently phallocentric, representing the sexual alternatives available only to the male erotic subject; female-female sexuality, therefore, had no place within its signifying system. The early twentieth-century sexologist Takada Giichiro characterized it for this reason as ‘irrational’ (fugōri) and ‘unscientific’ (hikagakuteki), a lexical embodiment of ‘male supremacy’ (danson johi). The dōseiai/iseai distinction, on the other hand, weighed the sexes of the parties in relation to each other, as if from the ungendered stance of an objective observer, and had the advantage of embracing male-female, male-male, and female-female forms of sexual behavior within a single taxonomy. In bringing the last two together under the rubric of ‘same-sex love,’ the new taxonomy implied that the resemblance between male-male and female-female sexualities outweighed their differences.” Pflugfelder, Gregory. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press, 1999, pp. 251-252.

Long, Daniel. “Formation Processes of Some Japanese Gay Argot Terms.” American Speech, vol. 71, no. 2, 1996, pp. 215–224, www.jstor.org/stable/455489. Accessed 12 August 2023.

“Tentacle erotica.” Wikipedia, www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tentacle_erotica. Accessed 10 August 2023.

Kruijff, Marijn. “Tentacle Erotica: Prepare For Some Notoriously Graphic Octopus Images..!” Shunga Gallery, 6 October 2019, www.shungagallery.com/tentacle-erotica. Accessed 12 August 2023.

“During the Edo Period, many stories began to be depicted as narrative art in the form of fuzokuga [genre paintings] and ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which had the effect of accelerating the tendency to depict the grotesque. This resulted in a style that was almost affected, in which excessive dramaturgy was conveyed in a baroque-style sensibility. Paintings referred to as seme-e [images of domination or punishment] and muzan-e [images of cruelty] provided catharsis to those who were drawn into the format of morality-based stories, and stems more from the visual pleasure and sensation of the images rather than from feelings of aggression or disgust. The familiar and extreme images that feature in shunga [erotic art] include bizarrely and acrobatically entwined men and women, or a woman entwined with a giant octopus, and can be described as the forerunners of pornography. At the same time, however, these fantastical and surrealistic works are more than simply images in which ethics are absent.” Hasegawa, Yuko. “Grotesque and cruel imagery in Japanese gender expression – Nobuyoshi Araki, Makoto Aida and Fuyuko Matsui.” The Persistence of Taste: Art, Museums and Everyday Life After Bourdieu. Malcolm Quinn, David Beech, Michael Lehnert, Carol Tulloch, and Stephen Wilson, eds. Routledge, 2018, pp. 236.

The baroque nishiki-e (錦絵) variation of the woodblock technique was developed towards the 1760s. This then hyper-innovative form of print was characterized by its many different layers of vibrant colors and color-gradients applied to create one single image, which were divided in separate woodblock matrices for each of the color patterns then printed in a step-by-step order.

“Bando family.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1250. Accessed 12 August 2023.

Gattuso, Reina. “The Learned Courtesan in Edo Japan.” The Curationist, https://www.curationist.org/editorial-features/article/the-learned-courtesan-in-edo-japan. Accessed 21 August 2023.

“Nakamura Tomijuro 1st.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1227. Accessed 12 August 2023.

“Onnagata.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1054. Accessed 12 August 2023.

“The Actor Nakamura Tomijuro as a Tall Woman in a Flat Straw Hat.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55167. Accessed 16 August 2023.

“Wakashu were, broadly speaking, male youths transitioning between being a child and an adult. But they were also more than just young men, occupying their own singular space with unique rules, conventions and, most crucially, their own style. Indeed, Wakashu were identified primarily through their clothes and hairstyles. They wore their hair in a topknot, with a small, shaved portion at the crown of the head and long forelocks at the sides, as opposed to adult men, who shaved the entire crown of their heads. Wakashu clothes were similar to those worn by unmarried young women: colorful kimonos with long, flowing sleeves. [. . .] Wakashu were connected to sexuality. As youth, they were considered largely free from the burdens and responsibilities of adulthood but regarded as sexually mature. As an object of desire for men and women, they had sex with both genders. The intricate social rules that governed the appearance of Wakashu also regulated their sexual behavior. With adult men, Wakashu assumed a passive role, with women, a more active one. Relationships between two Wakashu were not tolerated. Any sexual relationship with men ended after a Wakashu completed his coming-of-age ceremony.” Bohnke, Christin. "The Disappearance of Japan's 'Third Gender.'" JSTOR Daily, 22 December 2021, https://daily.jstor.org/the-disappearance-of-japans-third-gender. Accessed 20 September 2023.

Crossdressing is found in the very essence of kabuki theater. Around 1603 a new form of sensually-charged female theater practice known as 歌舞伎踊 (kabuki-odori) was created by 出雲 阿国 (Izumo no Okuni) and said to have been performed in the banks of the 鴨川 (Kamogawa) river at the heart of the thousand year capital: “This performing art used song and dance to play out scenes where female actors dressed as men visited teahouses and frolicked with the women there. People became crazy about this performance, and the audience included not only commonfolk but also even samurai warriors and nobility.” “The Beginning.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/unesco/kabuki/en/history/history1.html. Accessed 26 August 2023. Early Edo centralized patriarchal power became weary of the recognition and power gained by female actresses during these early iterations of Kabuki which was replicated by many different performance troops―who often gained copious amounts of influence moonlighting as highly ranked courtesans which where highly coveted by men of the upper social echelons―and in the year 1629 women were outlawed from the Kabuki stage altogether. This introduced a stark transition from what we now describe as 女歌舞伎 (onna-kabuki) or more pejoratively 遊女歌舞妓 (yūjo-kabuki) to an emerging interaction in which third gender 若衆 (wakashū) youths, constituted by males that occupied an androgynous role in society and were often courted by both male and female lovers, began crossdressing in female roles. However, a similar fate to its predecessor soon followed, and as wakashū thespians gained in influence and popularity they were eventually banned in the year 1652. “Wakashu-Kabuki.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1304. Accessed 26 August 2023. The current all-male iteration of kabuki that is still practiced since the Edo is known as 野郎歌.

“Silhouette Image of Kabuki Actor.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/58270. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Actor Onoe Taganojô II, from the series Portraits as True Likenesses in the Moonlight (Makoto no tsuki hana no sugata-e).” Museum of Fine Arts Boston, www.collections.mfa.org/objects/472080. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Chonmage.” Wikipedia, www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chonmage. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“The Third Segawa Kikunojo as a Woman in a Crouching Position.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36823. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Segawa Kikunojo 3rd.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1176. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Jūnihitoe” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C5%ABnihitoe. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Samurai and Wakashu (Male Youth).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/816213. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Kabuki Play Kusazuribiki from the Tales of Soga (Soga monogatari).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/670967. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Soga Monogatari.” 文化デジタルライブラリー [Culture Digital Library of Japan], www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/modules/kabukidicen/entry.php?entryid=1186. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Kusazuribiki.” Kabuki 21, www.kabuki21.com/kusazuribiki. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Parody of the Armor-pulling Scene (Kusazuribiki), from the series ‘Fashionable Parodies of Bravery in Love (Furyu mitate iro-buyu)’.” Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artworks/89108/parody-of-the-armor-pulling-scene-kusazuribiki-from-the-series-fashionable-parodies-of-bravery-in-love-furyu-mitate-iro-buyu. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Yatsushi kusazuribiki.” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2008660839/. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Demonen.” Rijksmuseum, www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-1991-687. Accessed 20 August 2023.

“Art: The Earth Spider Creating Monsters in the Mansion of Minamoto no Yorimitsu.” Annenberg Learner, www.learner.org/series/art-through-time-a-global-view/conflict-and-resistance/the-earth-spider-creating-monsters-in-the-mansion-of-minamoto-no-yorimitsu/. Accessed 20 August 2023.

aliwen is a 2023 Curationist Fellow. aliwen is a non-binary artist, critic, curator, and writer from Chile, currently based in Tokyo. Their research themes include the artistic representations and cultural heritage of queer, gender-variant or transgender people in regions such as Latin America and East Asia. They obtained their BA in Art Theory and History from The University of Chile, and received their MA in Art Studies and Curatorial Practices from Tokyo University of the Arts. Their first book Barricade Criticism. Body, Writing, and Visuality was published by Brooklyn/Santiago-based publisher Sangria Legibilities in 2021. Their recent projects include the Visual AIDS 2022 Research Fellowship.