Reconstructing Black Girlhood: Reading Photos Alongside Journal Entries

By Wendyliz Martinez•August 2024•20 Minute Read

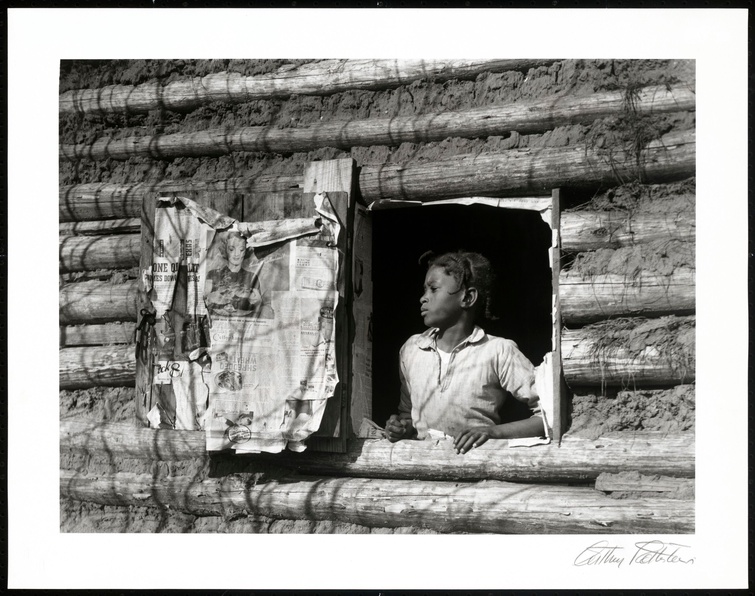

Arthur Rothstein, _Girl at Gee's Bend, Alabama,, 1937. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, CC0.

Exploring Black girlhood in the U.S. through photographic history reveals gaps, as institutional archives often neglect documents of Black girls’ lives and stories. Through a blend of research and imagination, we can attempt to fill in these gaps.

How do we grapple with the histories of Black girlhood in the United States of America as seen in photographs? Locations we associate with the holding of histories, such as institutional archives in museums and libraries, have not always been careful to preserve the histories of Black girls. Susan Sontag writes, “Photographs furnish evidence.”1 As I look for Black girls in the digital archives of the best known museums and collections in the United States, I can see that that is true. These photographs of Black girls confirm the existence of Black girlhood. Still, we are left to fill in the gaps of their lives—we often do not even know simple details like their names, where they lived, or when.

A Window into Black Girlhood

The girl in this black and white photograph strikes me. I see a young Black girl with plaits at the window of a log cabin. She looks away from the camera somewhere in the distance where we cannot see. The window frame has been insulated with newspaper and the window's shutter has newspaper pasted over the wood. The stance of the young girl is poised. She wears a light colored dress or shirt with a deep V-neck opening and a hint of a small stain. Her firm expression is emphasized by her clenched jaw. Her right hand is curled into a fist as her left hand rests on the edge of the window frame. What was she thinking? What was her life like? How did her clothes get those stains? How could she have known her image would live in an archive in perpetuity?

Artelia Bendolph, Gee’s Bend, and a Serendipitous Connection

I came across this image of a “Girl at Gee’s Bend, Alabama” first on the Curationist site. There was limited information available, leading me to research the photograph on other sites. The Cleveland Museum of Art did have more, though! They provide the name of the girl: Artelia Bendolph. They acknowledge that Gee’s Bend, the Black rural community she is from, is famous for its quilting tradition. I plug her name, Artelia Bendolph, into Google. I find her obituary. She died 21 years ago, in 2003.2 I read about her ancestors and her descendants, how she was loved by a community. I google her last name. An exhibition appears with several women from the same community with the same last name who have been part of that tradition of quiltmaking. Beautiful geometric shapes, patterns, and colors adorn these quilts.

The patterns look familiar. I look in my closet and find a tote bag I bought from Target during Black History Month—a tote bag labeled, “In collaboration with the quilters of Gee’s Bend.”

Wendyliz Martinez, personal photograph of Target tote bag, 2024. CC0. I included this image to show the collaboration between Gee’s Bend and Target. I realized the connection only after finding Bendolph in the archives.

Arthur Rothstein and the Farm Security Administration

Perhaps my subconscious grabbed on to Gee’s Bend in anticipation of when I would come across the image of Artelia Bendolph, perhaps the universe knew that something would activate my interest—something like deja vu. How many times have our paths crossed with that of a “historical figure” before we met them in the archives?

The photographer who took Bendolph’s picture was Arthur Rothstein, a Jewish photojournalist from New York. With a career stretching over five decades, he is best known for his photographs of rural America during the Great Depression.

In 1937, when he was 21 years old and freshly graduated from Columbia University, he was sent on assignment by the Farm Security Administration to photograph Gee’s Bend.3 This community was a former plantation where many Black residents became sharecroppers.4 Through this photographic assignment, the government agency hoped to highlight the impoverished conditions of residents and showcase the necessity for financial support of rural communities in the United States.5 As Sontag writes, “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and therefore, like power.”6 This photograph is an extension of Rothstein’s life’s work, his ability to capture rural America, but we can also choose to explore the lives of those photographed.

Artelia Bendolph is Unnamed in The New York Times

Rothstein’s photographs of the Gee’s Bend community appeared in The New York Times on August 22, 1937, in an article written by John Temple Graves II with the title, “The Big World At Last Reaches Gee’s Bend.”7 The article details the history of the community. It was at that time populated by about 700 Black people who were descendents of about 100 Black people enslaved on Mark Pettway’s plantation. After the Civil War, the descendants remained as tenants of others who owned the land: first Mark Pettway’s son, John; then an unnamed white family; and finally a Black family who are also unnamed in the article. As the title encapsulates, the article emphasizes the need that the Black residents of Gee’s Bend have for modern resources, and how these resources will bring the community into modernity.

Artelia Bendolph's photograph appears in this article alongside other photographs Rothstein took of the community. The photographs depict the cabins her family and neighbors lived in, children in front of the cabins, women working, and men smiling. Each and every photograph depicts the residents in a dignified manner despite highlighting their need for finances. Graves interviewed only the men of Gee’s Bend—despite the women and children pictured in the article—who he referred to as leaders of the community. The caption underneath Bendolph’s picture makes a reference to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Unnecessarily, the article flattens Bendolph to a character: “The girl (right) is not Topsy, the cabin not Uncle Tom’s, but they make a dramatic picture at Gee’s Bend.”8 The caption counters Bendolph's dignified presence in the image.

Patching Artelia Bendolph Back into Context

Looking at this image and centering Rothstein in this discussion gives him too much weight. It makes me aware that we know so much about the photographer and so little about the girl in the photograph. What can I know of Artelia Bendolph? What can I infer? By her stare and her clenched fist, we could guess she was tense. Her community, as detailed in the article, were in need of resources and they made it known. In December of 1933, the Civil Works Administration gave the men of Bendolph’s community part time work where they increased their 50 cents a day to 30 cents an hour. Then, in 1935, they became “‘clients’ of the Resettlement Administration.”9 The men of the Gee’s Bend community verbalize mixed feelings, some weary and some optimistic, about other Black people without familial connections to the former enslaved people of Gee’s Bend joining the community.

However, again, what of Artelia Bendolph? Were her feelings mixed? The Library of Congress has also created an informative description for the collection of images by Arthur Rothstein that feature Bendolph’s family.10 I could write about Artelia Bendolph’s family, and her community of Gee’s Bend. I can also write about the incredible work the Black women and girls have done with the Freedom Quilting Bee. Instead, I offer meditation. In applying other Black scholars’ incredible work on alternative ways to read what is available in the archives, we can imagine fuller worlds for Black people who have not been recorded fully in the archives.11 We must find ways to formulate narratives for the visuals we have of Black girlhood—beyond what is thought to be worthy to be preserved. The following meditates on and through other photographs found in the archives of Black girls who as of now remain anonymous.

Critical Fabulation: Weaving Together Personal Journals and Photographs of Black Girls

Saidiya Hartman coined the phrase “critical fabulation” to describe a method of using archival research and fictional narrative to fill in the gaps of the archive, particularly the omissions of information about the lives of enslaved people.12 In her 2008 article “Venus in Two Acts,” in which she first deploys the term, she carefully constructs from slim information a narrative of two enslaved Black girls finding each other on a slave ship before their murder. I wish to emphasize that care was a significant component of how Hartman approached the trial of their murders at the hands of a ship captain as narrated in the archives. She could have focused on the slave ship captain or the overseer. Instead she decided to explore what could have been or may have been the lives of two girls. Hartman writes about the ways that the “archive of slavery rests upon a founding violence.”13 Hartman emphasizes that she is unable to undo the violence these girls experienced, underscoring the need for critical fabulation to provide a perspective beyond the violence. Through careful speculation, critical fabulation allows a more comprehensive understanding of the lives of those rendered insignificant by the archives.

Not every girl I’ve encountered in my research has been named like Artelia Bendolph, not everyone has an obituary or comes from a well-documented place. However, there are still ways we could conjure “what could have been” for these girls as well. In what follows I position some mid-19th century journal entries from Charlotte Grimké alongside early-20th century photographs of Black girls to consciously and caringly conjure these narratives.

Charlotte Forten Grimké and Her “Unimportant” Journal Entry

Charlotte Forten Grimké (b. 1837, d. 1914) was a free Black adolescent who lived in Salem, Massachusetts, where she attended a private school. Grimké grew to be a prominent anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. Her journal begins when she was 16, in May 1854, where she writes, “A wish to record the passing events of my life, which, even if quite unimportant to others, naturally possess great interest to myself, and of which it will be pleasant to have some remembrance, has induced me to commence this journal.”14 Grimké’s declaration that the records of the events of her life would likely be “unimportant to others” may show significant awareness of how society regards the thoughts of not just adolescents but Black girls in particular. Despite this acknowledgment, she emphasizes that her records are important to her.

When it comes to the archives, this declaration is powerful, because institutional archives often privilege official records and voices that do not recognize or document the full extent of the humanity of Black girls (or other Black people). The lives of these girls, similar to how Grimké viewed her life, have all been important to someone, but especially to themselves. I am struck by another image as I scan the digital archives.

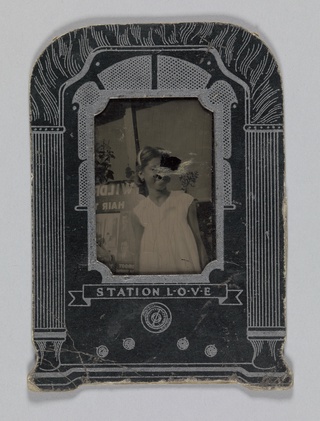

Station L-O-V-E, Grimké (Again), and Maxine Sullivan in the Bronx

Ironically, this image of a young Black girl, carefully framed by a printed radio, has been damaged where we would have seen her face. A hint of a smile peeks through the wear. This photograph is in black and white, like Bendolph’s. This image comes from the Maxine Sullivan collection. Maxine Sullivan was a jazz soloist; she also engaged in community work in the Bronx. Again, serendipitously, I am learning about an incredible Black woman who gave back to her community in many ways. Her community is also mine, as I was born and raised in the Bronx. In fact, she lived for over 40 years in a home just a 30 minute walk away from the building I grew up in. How many times have we both walked the same pavements? I return to a journal entry from Grimké:

Sunday, May 28 [1854]. A lovely day; in the morning I read in the Bible and wrote letters; in the afternoon took a quiet walk in Harmony Grove, and as I passed by many an “unknown grave,” the question, “who sleeps below?” rose often to my mind, and led to a long train of thoughts, of whose those departed ones might have been, how much beloved, how deeply regretted and how worthy of such love and such regret. I love to walk on the Sabbath, for all is so peaceful; the noise and labor of everyday life has ceased; and in perfect silence we can commune with Nature and with Nature’s God.15

Similar to the anonymous figures in the archives I encounter, Grimké encounters the anonymous figures of the grave. She wonders, as I do, about the lives of the people who are no longer known (or made known). This photograph feels different from Bendolph’s: perhaps this portrait was made as a keepsake. We can guess the photographer was familiar, if not kin to the young girl—her body does not appear tense like Bendolph’s. She is relaxed and smiling in her Sunday best, a light babydoll style dress. A headband holds her hair back behind her ears. How did this young girl’s photograph land in the Maxine Sullivan collection? Maybe it was handed down in her family, maybe she is related to Maxine Sullivan, maybe it was someone from her community. We are left wondering, who were the loved ones of the young girl with the Station L-O-V-E radio cardboard frame?

An (Un)known Toddler and the Forces Creating Anonymity

Another child appears on my screen. She is much younger than the young girl at Station L-O-V-E and Artelia Bendolph at the window. Like the girl at Station L-O-V-E, this infant, who appears to be almost a toddler, is not named. Again, she appears in a babydoll dress. Would this be the only photograph of this infant?

The young girl’s expression is neutral or curious—a common expression often exhibited by infants when confronted with a camera. The photograph is a sepia tone and has faded in some areas. The baby is sitting on wooden steps that lead to a door. Maxine Sullivan owned this photograph, too. Who is this infant? Was she an aunt, a niece, a cousin, or someone she so happened to collect from a thrift store? Or did she grow up to be Maxine Sullivan herself?

I come across another photograph in the digital archives of a young Black girl next to a white infant who is closer in age to the toddler on the wooden steps. This Black girl is much older. Because this image is a tintype, an older photographic process, and based on her apron and dress, it hints at the possibility of this girl’s enslavement.16 Was her role solely to attend to this infant or did she attend to the household as well? Is it possible that the infant only felt comfortable with her? Is that why the photograph is taken with her arm on the infant’s back? Was she possibly related in any way to the white child? None of these questions can be answered. There is a discomfort that elicits the tense feeling from Bendolph’s curled fist and clenched jaw. The tenderness from the photos of the toddler on the wooden steps or the girl at Station L-O-V-E do not translate to this tintype. Again, this girl’s anonymity prevents us from learning more about her.

Yet despite who these girls may be, the photographs are significant evidence of their existence. Though we may never know their names, we have crossed paths with their likenesses. How many times have we unknowingly engaged with the histories and futures of these girls?

I think back to the obituary of Artelia Bendolph. “She leaves to cherish her memories,” the obituary states, as it lists devoted family members who will continue to remember their relative.17 Her family continues to breathe life into the “Girl at Gee’s Bend” with the memories that they perhaps share with their own descendants. I am compelled to believe each of the girls unnamed have also had loved ones who uphold their memory. The period in which these images were taken is noted in the archive as vaguely the 19th or 20th century. The inability to narrow down even a year makes it difficult to track their presence in time. They are anonymous after all, leaving no writing on the back to trace to a public record; no full frame of the background to trace an address or named establishment.

Grimké, Class, and Narratives of Black Girlhood Retrieved Through Scholarship

It is significant we have narratives from girls themselves. The anonymity in the images underscore that significance to understand Black girlhood across time. Grimké’s journal provides us access to the inner thoughts of a young free Black adolescent within the Northeast United States, the only African American in the private school she attended. Grimké’s journal is just one type of experience, however, and cannot account for narratives of Black girls who were from a different economic, social class, and who were previously enslaved.

Scholars such as Lakisha Simmons and Marcia Chatelain have taken on the task of searching for such narratives of Black girlhood in the early- to mid-20th century within the archives.18 19 Their works provide fuller pictures of what Black girlhood was like in neighborhoods of New Orleans and Chicago. Within their work, they detail the fullness of these girls' lives. Chatelain opens her book South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration with letters penned by Black girls. In these letters, the girls were seeking jobs with better pay than what they would receive in their communities and wrote about how tired they were of the impoverished conditions and lack of opportunities where they lived. Chatelain focuses on the Black girls who arrived in Chicago. However, as she makes clear, “These girls shared the concerns of the masses of southerners who heeded Abbott’s call to head North—including a lack of educational opportunities, a sense of stagnation in the South, and low wages earned at the jobs that were necessary to support their families.”20 While the class status may be different, we can tell from the narratives we do have from Black girls that they seemed aware of many of the systemic racist injustices that impacted their families, their communities, and themselves.

On August 17th 1854, Grimké wrote an entry on her 17th birthday:

My birthday—How much I feel to-day my own utter insignificance! It is true the years of my life are but few. But have I improved them as I should have done? No! I feel grieved and ashamed to think how very little I know to what I should know of what is really good and useful. May this knowledge of my want of knowledge be to me a fresh incentive to more earnest, thoughtful action, more persevering study! I believe it will.21

Grimké demonstrates an awareness of her own positionality. However, we can counter her own words: She was not insignificant. No one girl is the same, but they have perspectives to offer us about our realities and our pasts. As Grimké grew older she also participated in abolition efforts.22 Reading her journal allows us to understand Black girlhood historically and provides another perspective of the fullness of what that could be.

A Return to Artelia Bendolph and Her Thoughts

All these girls had their community lives and private thoughts. I wonder about the girl in the window at Gee’s Bend. What would Artelia Bendolph’s friends and family say if we had the opportunity to speak to them?

This is a picture from Gee’s Bend.23 We see some of her community and perhaps even her family. On the far right we see a young girl who I imagine might be Bendolph, as the collar of this dress looks similar to that of the girl at the window.

We have words, too, from the people of Gee’s Bend. Souls Grown Deep is an organization that “advocates the artistic recognition and empowerment of Black artists from the American South.”24 They have kept records of the women of the Gee’s Bend community who have created quilts. They have published first-hand accounts, often told in first person, detailing what life is like in Gee’s Bend. Mary Lee Bendolph, in an interview featured on Souls Grown Deep, says, “Families down here, they like to do together. See, we farm together, and the ladies in the family get together for quilting… Piece by yourself; quilt together.”25 The interviews of the women of Gee’s Bend each echo each other; each emphasize the community aspect of the act of quilting while also providing details of their life on the farm.26 These interviews give a different perspective than the New York Times article written 86 years ago. Their emphasis on community reflects how Artelia Bendolph was remembered in her obituary, as a woman loved by her Black southern community.

Wendyliz Martinez is 2024 Curationist Critic of Color. She earned a PhD in English and African American Studies at Penn State University. She is a City College of New York and Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow alumnus. She is writing about how Black girlhood is represented in film, social media, and literature. Particularly, she is interested in how Afro-Caribbean women writers depict Black girlhood compared to U.S. Black women writers. She also researches Black portrait photography from the 19th Century and beyond and its influence on Black visual culture.

Citations

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977, p. 3.

“Artelia Bendolph Obituary.” Alabama Press-Register, https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/mobile/name/artelia-bendolph-obituary?id=8350733. Accessed 27 August 2024.

"Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.” Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/docchap5.html. Accessed 5 June 2024.

“Sharecropping.” Slavery By Another Name, PBS, http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/sharecropping/. Accessed 20 July 2024.

“Farm Security Administration.” Oklahoma Historical Society, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=FA015. Accessed 5 June 2024.

Sontag, p. 2.

Graves, John Temple II. "The Big World At Last Reaches Gee's Bend." The New York Times, 22 August 1937, https://www.nytimes.com/1937/08/22/archives/the-big-world-at-last-reaches-gees-bend-amid-changes-wrought-by-the.html.

Graves.

Graves.

“Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/docchap5.html. Accessed 12 July 2024.

See Hartman, Saidiya V. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019. See also Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Hartman, Saidiya. "Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe, vol. 12 no. 2, 2008, pp. 1–14, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/research/centres/blackstudies/venus_in_two_acts.pdf.

Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” p. 10.

Forten, Charlotte L. The Journals of Charlotte Forten Grimké. New York : Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 58. Internet Archive, http://www.archive.org/details/journalsofcharlo0000fort.

Forten, p. 62.

Slave Clothing | George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/slave-clothing. Accessed 6 July 2024.

“Artelia Bendolph Obituary.”

Simmons, LaKisha Michelle. Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Chatelain, Marcia. South Side Girls: Growing up in the Great Migration. Duke University Press, 2015.

Chatelain, pp. 1–4.

Forten, p. 96.

“Charlotte Forten Grimké.” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/people/charlotte-forten-grimke.htm. Accessed 20 July 2024.

Rothstein, Arthur. “African American Family at Gee’s Bend, Alabama.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/284663. Accessed 1 July 2024.

Souls Grown Deep is an organization that “advocates the artistic recognition and empowerment of Black artists from the American South.” They have kept a record of the women of the Gee’s Bend community who have created quilts. They have published first-hand accounts, often told in first person, detailing what life was like in Gee’s Bend. See “About Souls Grown Deep,” Souls Grown Deep, http://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/about. Accessed 8 June 2024.

“Mary Lee Bendolph.” Souls Grown Deep, http://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/artist/mary-lee-bendolph. Accessed 8 June 2024.

“Gee’s Bend.” Souls Grown Deep, http://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/gees-bend-quiltmakers. Accessed 8 June 2024

Wendyliz Martinez is 2024 Curationist Critic of Color. She earned a PhD in English and African American Studies at Penn State University. She is a City College of New York and Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow alumnus. She is writing about how Black girlhood is represented in film, social media, and literature. Particularly, she is interested in how Afro-Caribbean women writers depict Black girlhood compared to U.S. Black women writers. She also researches Black portrait photography from the 19th Century and beyond and its influence on Black visual culture.

![[African American Family at Gee's Bend, Alabama]](https://img.curationist.org/sbWvXuE3MT0EqAVyJ8q6nPEtUmkKMRkj4m0R6GhMzWv0,320x/https://images.metmuseum.org/CRDImages/ph/original/DP212791.jpg)