Metadata Learning and Unlearning Summit 2023

By Sharon Mizota and Jessica Gengler•June 2023•21 Minute Read

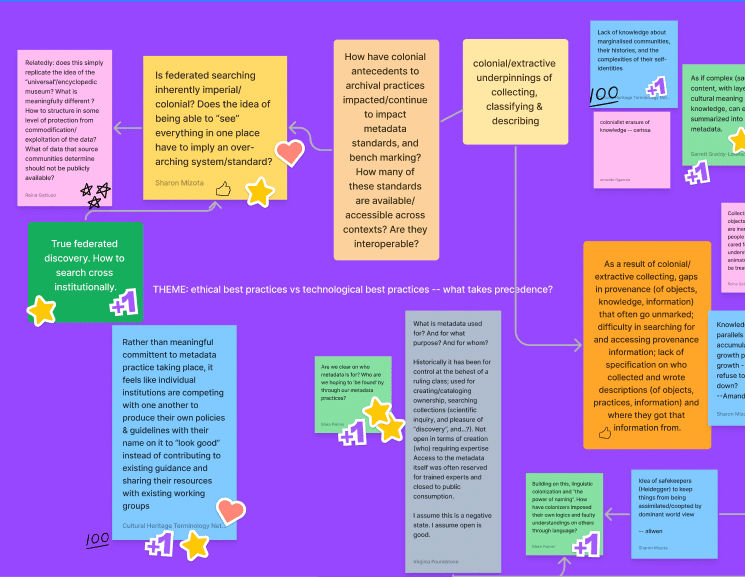

Detail of a FigJam board created by participants in the Metadata Learning and Unlearning Summit, June 21, 2023.

This document is a summary of conversations that took place virtually at the first Curationist Metadata Learning and Unlearning Summit on June 21, 2023. It was prepared by Sharon Mizota and Jessica Gengler, and edited by Reina Gattuso. The goal of the Summit was to bring together participants from the global cultural heritage community to discuss issues and commitments in creating more inclusive metadata in our fields.

Introduction

Fourteen participants—writers, scholars, archivists, and librarians—joined in the Summit. This gathering was organized by Curationist Platform Director Amanda Figueroa, Metadata Consultant Sharon Mizota, and Digital Archivist Jessica Gengler.

The other participants were: aliwen, Curationist Fellow; Blake Palmer, Writer; Carissa Chew, Inclusive Metadata Consultant; Christina Stone, Senior Assistant Registrar for Collections, Harvard Art Museums; Garrett Graddy-Lovelace, Provost Associate Professor, School of International Service, American University; Meg Ocampo, Archivist/Records Manager, SFMOMA; Nebojša Ratković, Curationist Fellow; PP Sneha, Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), India; Reina Gattuso, Contributing Writer, Curationist; Treshani Perera, Music and Fine Arts Cataloging Librarian, University of Kentucky Libraries; Virginia Poundstone, Senior Product Manager, API Platform, Wikimedia Foundation.

The Summit took place in two 90-minute sessions, which Amanda facilitated, via Zoom. We posed the same questions in both sessions, which were held separately to accommodate participants in different time zones. This report synthesizes discussions from both sessions.

We asked three guiding questions:

What are the legacy problems in metadata? What issues are present in the field that need to be addressed? What are our political commitments in metadata work? What do we want to support/enfranchise with these best practices? What format or type of document best suits our goals?

Before and during the conversations, we asked participants to contribute to a FigJam board. The board was initially organized with three sections, one for each question. As the conversations developed, we added a fourth section for “Additional Links and Resources.” As common themes emerged, they were recorded on the board with the heading “THEME.”

After the Summit, Sharon and Jessica reorganized the board to group contributions together according to theme. This document is a summary of these contributions. We hope that it will provide direction on how to move these conversations, issues, questions, and suggestions forward toward a framework for metadata practices that foster inclusion, cultural sensitivity, and social justice.

We made an effort to associate contributor names with their comments on the FigJam board. For the purposes of brevity and flow, we will not attribute the points summarized in this document to individual contributors. We appreciated everyone’s thoughtful participation.

A note on language

In writing this document, we found an opportunity to reflect on our use of language, in particular terminology that has become common in the fields of archives and metadata. Terms such as “assets” (describing objects and knowledge) and “capture” (describing the recording of data or images) carry colonial and capitalist associations with property and its nonconsensual extraction. We have tried to avoid this language as much as possible in this report, but have used it where it makes sense to highlight the capitalist and colonialist nature of the activity.

SECTION 1: What are the legacy problems in metadata? What issues are present in the field that need to be addressed?

This discussion largely dealt with the tensions between ethical cultural heritage stewardship, and the structures and demands of technology and information systems designed in alignment with extractive, colonial, and capitalist values.

Three broad themes emerged:

Ethical best practices vs technological best practices — what takes precedence?

Contributors identified the colonial, extractive underpinnings of GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) work. We named that, due to the historical origins and entrenched power structures of these fields, GLAM work typically involves collecting, classifying, and describing objects through a Euro- and Euro-American-centric lens. This lens obscures forms of knowledge and creates erasures, particularly in provenance information. There often isn't an accurate record of how physical objects were acquired, and how information was sourced and recorded. There is also a lack of knowledge about the histories and self-identifications of communities that colonial systems marginalized.

When it came to aggregation and federated discovery, we asked: Are these systems, with their “one stop shopping” approach to organizing and locating knowledge, inherently imperial or colonial? Considering the colonial origins of the “universal” or “encyclopedic” museum, we discussed whether the goal of being able to “see” everything in one place leads to an overarching system or standard that may not accommodate, or may flatten, many different forms of knowledge.

In general, metadata has been created and used by the “ruling class” to exert control over objects and knowledge. The people creating metadata are typically from a professional or managerial class, often in the Global North. This leads to the exclusion of a vast range of experiences and knowledge systems.

Summit participants asked: Who is metadata for, and who are its audiences? Who does metadata help? For whom does it facilitate access, and whom does it exclude? Do people who are not in related professional fields have access to baseline knowledge about what metadata is or what it does?

While some contributors focused on gaps and erasures left out of metadata, others drew attention to information or experiences that metadata cannot or should not describe. For example, many objects and kinds of knowledge are sacred within their communities of origin, to be accessed only by those with community or ritual consent. Metadata, in this case, is perhaps too reductive or simplistic to capture this information; in attempting to do so, it may cause harm. Metadata is also generally produced by a dominant knowledge system that assumes that objects are inanimate “things” as opposed to animate beings. In contrast, many communities consider some forms of knowledge or objects alive. Contributors compared the process of knowledge accumulation to capitalist accumulation, with its ethos of infinite growth. Are there things that should not be written down?

Is there a way to protect objects or experiences from cooptation and description under the dominant worldview? Contributors raised the issue of linguistic colonization, where the structures and values inherent in language are imposed on objects and experiences that don’t adhere to them. This is particularly reflected in the hegemony of English on the Internet.

Tensions between consent, control, and free and open metadata

Contributors brought up the political economy of the Internet, where everything seems to be shared freely, but is actually increasingly controlled by large corporations, which enact new forms of censorship and surveillance through digital technologies. They highlighted the increase in digital disinformation and misinformation, and how biases of corporate elites are built into search engines, which control what can be found and accessed. Purported values of openness and sharing are undergirded by realities of control and suppression.

Additionally, these systems amass a great deal of data that was collected from communities of origin without free and informed consent. What are the legal and privacy issues raised by open data collection and sharing? How do we protect and respect privacy while championing greater transparency and access to data? Can, or how can, this framework honor cultural prohibitions on sharing certain information or experiences?

These unanswered questions underscore the perceived tension between the need or desire to control the circulation of metadata, and the desire to expand access to it. We want to share metadata and open it up to more voices, while acknowledging that the systems we use to do so are driven not by openness, but by profit, censorship, and ownership. At the same time, we want to be able to invoke structures of community ownership and self-determination to protect content and experiences that should not be indiscriminately shared. The former conception of ownership is based on profit; the latter, on cultural imperatives. Some participants viewed this as a conundrum.

Standardization, technological limits and abilities

Building on these thoughts, we asserted that technology is not neutral; it is built on inherited extractive, capitalist, wartime values, but should be used for the betterment of humanity. Technology should be devoted to human thriving. We asked how we might use technology and the social realm to mend tensions created by historical metadata practices. We also discussed the difficulty of describing objects or experiences related to social movement struggles without codifying them and separating them from the life of the movements themselves.

Current systems, however, are limited in the kinds of things they can represent, document, and describe. There are multiple schemas for structuring and organizing metadata, including “local” ones customized to particular needs and audiences. Because it specifies the kinds or “buckets” of metadata that can be recorded, a metadata schema necessarily constrains what can be communicated. However, traditionally, the emphasis in the literature has been on mapping between different schemas, or how metadata is transferred from one schema to another. This process involves matching the elements, or fields in one schema with the corresponding ones in another schema. We highlighted the necessary losses that occur in this process, as different schemas do not always easily align with one another. We who work in this field need to acknowledge and take ownership of the limitations of our own perspectives and how they have determined what can and cannot be represented; this is necessary to make space for people whom our institutions exclude. We also talked about “paradata,” or data about how data is collected, and how it is vital to record and acknowledge this so users can understand the perspective represented by the metadata that is available. Similarly, it is important to reveal the debates that happen around each field and label, in a way that users can access. We also discussed the importance of recording in the metadata when we don’t know something or are uncertain.

Within this theme, too, we touched on the hegemony of English and the things that are lost in linguistic translation of metadata — including acknowledging the valuable, interpretive role of the translator. There isn’t always a one-to-one correspondence between terminology in one language and another. What conceptual remapping happens (or doesn’t) in translation of metadata? We also need to account for linguistic barriers in access to technology, how certain systems and code are inherently more accessible to native English speakers.

We began to imagine metadata that is multi-modal, or that can be used in multiple ways, and interactive across many different Internets, not just one.

SECTION 2: What are our political commitments in metadata work? What do we want to support/enfranchise with these best practices?

In this discussion, we looked at our values and goals for inclusive, open metadata. Five broad themes emerged: accessibility & openness, labor, consent, local vs. global, and intersectional power relations.

Accessibility & Openness

We agreed that everyone should have unrestricted access to learning and that we cannot support open access metadata without supporting Internet access as a human right. We support accessibility, shared power and authority, flexibility and extensibility for an Internet that is collectively owned and shaped. We understand that collective ownership can be messy, and that’s okay.

Part of this is dismantling intellectual property regimes that further colonial, capitalist enclosure and expropriation of information for profit. We support the creation of open, liberatory, popular education, particularly in the current climate of neo-fascist censorship and control in higher ed and K-12 education.

We support infrastructure that enables free and open Wiki-style, human contributions to metadata, which might be deemed “artisanal” or “bespoke.”

Labor required to create inclusive metadata

This brings us to the issue of labor, an area where we had more questions than answers. Creating metadata is labor and the amount of work that needs to be done is overwhelming. Since labor is finite, how do we ensure that it’s allocated where it’s most needed? How do we prioritize the issues and communities that deserve the most urgent attention? How do we decide what language/imagery/omissions are most harmful and should be redressed first?

We also need to ensure that metadata work is paid work. How does that fit with the idea of “free and open” participatory metadata? Wikipedia contributors are volunteers; what is a sustainable model of metadata creation that isn’t extractive, exploitative, or privileges those that have the access and free time to create it?

Who does metadata work currently? And how do we diversify the pool of people who do it and make decisions about what gets described?

We decided that the process of metadata creation is as important as the data itself, and that we need to focus on process as much as product. How can creating metadata be a way to redistribute funding, a means of interactive learning, and a way to recenter relationships?

By focusing on “Dialogic Co-Annotated Metadata Layering,” we advance a vision of metadata that is designed to address human needs and capacities, rather than AI or systems-driven priorities. This metadata is dialogic, in the sense that it arises from or anticipates dialogue or interaction between two or more parties. Similarly, it is co-annotated in that it allows for multiple people to contribute metadata to the same record or metadata field. Finally, this process allows for layering, for all such metadata contributions to be visible and available simultaneously. In this sense, metadata should be “artisanal” and “bespoke” rather than generic and mass-produced, even though we recognize this requires significant human labor.

Consent to label, consent to aggregate, consent to identify, consent to be discoverable

This conversation centered around how to make consent (or the lack thereof) more visible and avoid situations where metadata and other assets are taken or used without consent. Again, there were more questions than answers!

We discussed the need to build self-identification into the process of metadata creation by being transparent about who authors metadata on an individual level, rather than attributing it to a faceless institution. We acknowledged the need to practice accountability by recording changes to the metadata. We also noted how this may be at odds with aggregation, where “credit” for individual pieces of metadata can get lost in ever larger, homogenized datasets. Is there a point at which aggregation and standardization have gone too far?

If discoverability is the goal, how does metadata layering facilitate or interfere with that goal? By “metadata layering,” we mean the ability to store and display different metadata contributions from different people for the same data point or item. In this way, a single record could represent multiple points of view on its contents. Metadata layering may provide additional access points, but does it just provide more fodder for data scraping into larger aggregations, where it loses its context and becomes grist for AI and Large Language Models (LLM)? Is that a bad thing? Do we want to diversify the LLMs or avoid them? Would any metadata intervention we could make have an impact? How does the need to protect certain metadata from aggregation square with our commitments to open and free educational access?

Local vs global metadata

This theme was focused around how, as most of us are based in North America or work with North American institutions, we can have an impact that is truly global without centering our own frameworks and contexts. How can we have a conversation about metadata that is multi-directional? Can we learn from non-Western institutions and communities in a way that is not extractive?

How do we avoid exporting North American frameworks of identity and power, including those of race and gender, to contexts where they may not be appropriate? Even when we think about “social justice,” many of us are limited by the parameters of the debate in the U.S. The language we use to talk about, for example, race and indigeneity doesn’t always apply or make sense in other locales because contexts, histories, languages, power dynamics and hierarchies differ around the world. We who are located in North America need to be more explicit in acknowledging our limitations and listening to people and groups located outside of Western/Northern institutions.

We discussed feminist and queer models of centering marginalized experiences, although some of us expressed resistance to the label “feminist” as being too closely identified with white womens’ experience. How can we center non-dominant experiences and ways of knowing without projecting our own understandings of gender expression and categories onto contexts where they are inappropriate or don’t make sense?

Is the way we even talk about dominant and marginalized communities in this process too reductive?, when we use terms like BIPOC and LGBTQ+ for expediency, for example, do we risk reinforcing the norm that we seek to criticize by implying communities (who may in fact be global majorities) are “other”? These terms are helpful for discovery, but can flatten context and reify oppression. We need to be clearer about our position in relation to these terms when we use them. Are we using them to “other” people, or do we self-identify and claim them for ourselves?

There are multiple internets with multiple hierarchies and power relations!

This discussion echoed others in emphasizing the need to acknowledge the position, power, and privilege afforded English-speaking, North American-based people on the Internet. The dominant infrastructures of the Internet are largely created by and for these people (most of the participants in this Summit). Yet this can also obscure the fact that there are many different Internets depending on what languages you use, what abilities you have, and what resources you have access to. No one person, institution, or organization can possibly have the expertise to accommodate and include all of these positions in their metadata. There will always be problems of translation and missing cultural context when a resource is translated into another language.

So any effort to diversify and improve metadata will require a diversity of people, perspectives, abilities, and approaches. We don’t want to continue reproducing extractive and biased models that characterize certain knowledges and experiences as marginal or supplementary to the “main” narrative. Thus, metadata ethics should emphasize accessibility and co-creation, or shared authorship/ownership.

SECTION 3: What format or type of document best suits our goals?

In this section, we talked about a final form for the outcome of these discussions. In the process, we identified four themes: the audience for this resource, open-ended interactivity, the written word, and ethics and guidelines.

Who is this resource for?

Although we didn’t come to any conclusions on who the audience for this outcome is, we did identify some things to consider in creating a resource:

- • Those who may have limited access to the Internet

- • Multiple languages with the ability to be translated

- • Format, including video tutorials and printed materials

One broad audience we did identify is educators and learners, including K-12, college, lifelong learners, and students of all types/levels/regions.

We also agreed that community-building around this work was important.

Open-ended, interactive

We liked the idea of creating an interactive, open-ended resource, in the vein of resources like Bawaka Collective’s intercultural communication handbook. But we also recognized that the field is full of toolkits, as institutions try to virtue-signal by publishing their own guides.

Whatever we create should be messy, include multiple perspectives, and acknowledge that we don’t have all the answers. Maybe it’s something like a Wiki-project, where a group of people set out to accomplish a shared goal, presuming there is a platform on which to do this.

We also noted that open resources are labor intensive, requiring hosting and updating on a regular basis to stay relevant. Is there a sustainable way to do this?

Written word

We brainstormed some ways in which the outcome could take a written form.

- • As a toolkit for professionals, it could be downloaded and used to help make decisions on the job.

- • It could also be a resource on how to critically consume and evaluate metadata.

- • It could be a blog, or the generation of criticism and theory.

- • An admired example: https://womenscenterforcreativework.com/a-feminist-organizations-handbook/

- • It could be guidelines and best practices.

- • It could be an invitation.

Outside the realm of written documents

We also talked about options that didn’t involve the creation of documentation.

- • Listening sessions

- • Once a year in-person gathering and monthly calls, time-shifted to accommodate different time zones, with different facilitators.

- • Courses/webinars on inclusive metadata, including how to look critically at metadata for researchers & other users (non-professionals) who aren’t creating it, a kind of metadata literacy project

- • Situated engagement with metadata

- • Workshops and capacity-building, co-created with other GLAM institutions

Ethics and guidelines for this resource

Whatever form the outcome takes, we talked about the values we want to embody in its creation and circulation.

- • Build a community of practice

- • Have a clear, public data governance policy that explicitly states how data will be used

- • Lean into the iterative process of this work, with versioned iterations so changes and corrections are clear

- • Decentering the self (whether that be the personal or organizational self!). Moving with humility! Acknowledging we are working in relationships with thousands of people whose knowledge is in these archives, whom we don’t see or know, but whom we are accountable to.

SECTION 4: Additional Links and Resources

Collaborators suggested additional links to projects and resources that resonated with our collective work. They are included here with the participant that suggested each resource:

Inclusive Terminology Glossary – Sharon Mizota

Metadata Learning and Unlearning blog – Sharon Mizota

Europeana DE-BIAS project (example of an AI tool) – Carissa Chew

https://www.situatedengagement.org – Amanda Figueroa

Centre for Internet and Society – Sharon Mizota

Paradata, data about how the data was collected – Sharon Mizota

Digital Benin An example of community-centered knowledge production about stolen cultural heritage using multiple forms and presentations of knowledge and using local language metadata terminology (oral history, storytelling, critical reflections on metadata and archiving). – Reina Gattuso

https://whoseknowledge.org/ – Garrett Graddy-Lovelace

Mukurtu - CMS designed for Indigenous collections – Sharon Mizota

Conclusions

While this process raised more questions than it answered, the discussions emphasized a few common values and guidelines around which a community of practice or other outcome can be based.

-

• The problem of colonial, capitalist, extractive, patriarchal metadata is overwhelmingly large, deeply entrenched, and still zealously gatekept. Although things are changing in the metadata landscape, with reparative efforts and more inclusive strategies, we are still waking up to the amount and complexity of work to be done. In fact, due to its colonial history as a method of control and classification, the concept of metadata itself may work explicitly against liberatory aims.

-

• The technology that supports the sharing and creation of metadata is also deeply entrenched in colonial, capitalist systems and must be deployed carefully and creatively to foster more inclusive metadata.

-

• Metadata work is labor and should be compensated.

-

• Truly inclusive metadata comes from the peoples and cultures it describes, including the right not to describe.

-

• We need to diversify the pool of people who create metadata in order for it to be more accurate and representative of cultures and communities.

-

• We need to constantly and consistently reflect on our own biases and perspectives and expose them in the creation of metadata through the use of paradata or other contextual information.

-

• We assert the importance of “artisanal,” or “slow” metadata created with care and respect, bucking trends that privilege speed and efficiency.

-

• Context is everything, and translation always involves loss.

-

• Metadata should be shared freely and openly in support of human flourishing, except in cases where cultural imperatives require its consumption be limited to a particular group.

-

• The outcome of this Summit should support community-building, resource-sharing and be global.

Sharon Mizota is a DEI metadata consultant who helps archives, museums, libraries, and media organizations transform and share their metadata to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in the historical record. She has over ten years of experience managing and creating metadata for arts and culture organizations. She is also an art critic, a recipient of an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers’ Grant, and a coauthor of the award-winning book, Fresh Talk/Daring Gazes: Conversations on Asian American Art.